Although China officially ended its decades-long one-child policy in January, millions of parents who had previously given birth to two or more children are still dealing with its aftermath.

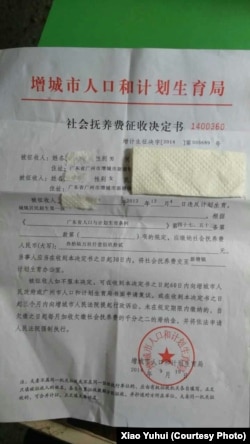

Many are still burdened with fines, known as "social maintenance fees," and their children remain unregistered as legal citizens.

Fines, a nightmare

Fan Ziting, 36, is still dealing with the impact of the controversial policy and was among 30 couples who petitioned outside the health department of Guangdong province Tuesday, urging authorities to reconsider their situation.

Fan had her first child in 2008, and three abortions afterward. When she became pregnant again in 2014, she was torn. Knowing that family policies were loosening, she and her husband decided to go ahead with the pregnancy.

The delivery of their second child last April came eight months before China completely lifted its decades-old one-child policy, allowing all couples to now have two children.

In response, authorities fined the couple $28,500 – six times their annual incomes as factory workers. The local government also canceled the family's annual bonus of some $1,530 from their village for 10 years after a village-owned property was leased for rental.

Although the Fan family of four is the ideal model of what the government is now advocating, the Fan family’s situation has become a nightmare as it struggles to make ends meet.

“The fines are too much and more than we can afford, which puts a lot of pressure on us. That’s also what keeps us from registering our second child [as a legal citizen],” Fan said.

Before it was relaxed in early 2014 and officially ended this year, China’s one-child policy was enforced at the provincial level and enforcement varied as it was within the local government’s discretion to impose penalties or forced abortion.

Forced abortion was one of the reasons thousands of Chinese couples were said to have sought asylum overseas each year in the past two decades.

In Zhejiang province, 29-year-old Dong Yulong faces a pending fine of $21,400 – four times his family’s annual income – after his second child was born five days before the province was the first in China to allow couples (on January 17, 2014), one of whom is an only child, to have two children.

Although his 2-year-old is now legally registered, Dong decided to take his case to court, seeking to further nullify the fine on him.

“I think a legal action is worthwhile because child-bearing should be a fundamental right to all of us as humans,” Dong said.

Dong’s lawyer, Wu Youshui, argued that no fines should be imposed on either Dong or Fan because their violations occurred during the transitional period, after the central government had confirmed the policy direction and before the relaxation was officially implemented.

“During the transition, whether the new law or old law should apply, it should depend on which law benefits the party concerned more. It is a legal principle also known as the principle of interest in the party concerned,” Wu said.

Calling the birth control policy “a mistake,” Wu further urged Chinese authorities to call off all fines on millions of couples who had broken the law to have two children.

According to a nationwide census in 2014, China has as many as 13 million unregistered citizens, half of them are illegal second children.

The flow of fines questioned

The lawyer further challenged the legality of the fines. Wu’s inquiries with 24 provincial governments found that more than $310 million had been collected in 2012 in the name of social maintenance fees, but no local government could detail where and how the money was spent.

Wu, nevertheless, was pessimistic that authorities would allow redress, especially for civil servants who were removed from their jobs for having two children.

Last week, 32 former employees of government-affiliated institutions from nine provinces who were dismissed for having a second child petitioned the State Council to give them their jobs back in light of the two-child policy.

Chen Yaya, a researcher with Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, also echoed her opposition to China’s birth planning policies, which she said infringed basic human rights, including women’s birth rights and children’s rights to survival.

“On a national level, incentives should be given to encourage couples to have more or fewer children in accordance with the government’s birth control plan. No governments should impose mandatory or punitive measures to enforce birth control,” Chen said.

The researcher said that many problems remain to be addressed in the aftermath of the one-child policy’s termination.

As a cure-all, Xiao Yuhui, a farmer-turned-activist from Guangdong province, advocates abolition of the nation’s birth control policies, allowing couples autonomy to decide how many children they plan to have.

“We believe the collection of social maintenance fees is illegal. Hence, we’re calling [on] the government to completely abolish any of the nation’s birth planning policies,” he said.