At America’s southern border, pandemic-related restrictions continue to block most migrants from filing claims for asylum in the United States. New arrivals, including large numbers of children, have settled into border encampments and shelters hoping for a change in U.S. policy.

As the months drag on, one organization has marshaled former teachers among the tent dwellers to give daily classes for migrant children.

The Sidewalk School for Children Asylum Seekers started almost three years ago as a Texas couple’s effort to keep up with the humanitarian crisis on the border. This month it officially registered as a U.S. nonprofit organization and opened its largest school yet. Some 10 teachers are providing instruction to roughly 500 children in three massive tents erected in a squalid encampment a few blocks away from the bridge linking Reynosa, in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, to Hidalgo, Texas.

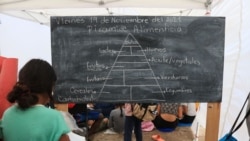

Under one of those tents, 36-year-old Josue Herman Sanchez Mendoza spoke into a microphone in front of dozens of students, ages 10 to 17, who had gathered for a social science class. He talked about a set of virtues the students should embrace: honesty, patience, tolerance, respect, generosity and willpower.

“If we don’t practice our values, our lives will be more difficult,” Sanchez told the students seated in rows atop foam mats on the ground.

Sanchez used to be an academic, an investigator at the Honduran Institute for Anthropology and History. Then he and his family, like his students and their parents, abandoned their homes and made a treacherous weeks-long journey to the U.S. border.

Sanchez said he paid various traffickers a total of $17,500 for his family of five to travel a month across Mexico. They hiked hidden jungle trails and congested roads. They stood for 72 hours in a jam-packed bus and rode 36 hours in a sweltering truck trailer with 40 other people and no bathroom. They waited five days in one hiding house and four days in another.

“It’s the kids who most suffer. As an adult I understand that I’m a refugee, but a child doesn’t,” Sanchez said. “A child just says, ‘I’m hungry, I’m cold, I want to bathe.’ A parent feels impotent.”

About a month after they left home, Sanchez and his family floated across the Rio Grande on inflatable rafts and scrambled to U.S. territory. U.S. Border Patrol found them and their group, processed them and drove them to the Hidalgo-Reynosa bridge in late September.

Since then Sanchez has lived in the camp, eating simple food provided by local churches and helping the Sidewalk School organize daily instruction, which began earlier this month. He now teaches social science classes every day.

The Sidewalk School came about in 2019 when Felicia Rangel and Victor Cavazos of Brownsville, Texas, started organizing short informal classes on a sidewalk near a camp in Matamoros, Mexico, 90 kilometers from Reynosa.

The project has since raised more than $300,000 in grant funding. It serves food every day at the camp in Reynosa, sponsors 11 portable bathrooms there and pays rent on about 20 apartments for vulnerable asylum seekers and office space across the street from the camp in Reynosa. It also runs four smaller school projects in the area.

Rangel, 45, said she’s met four times with Biden administration officials, in person or by video call, to answer questions about the situation across the border. U.S. government funding for the project has been requested but has yet to materialize, Rangel said.

“There are so many things we have to do every day just to keep people going, to keep alive their hope,” she added.

For many people, hope was wearing thin in the camp as winter months approached and the U.S. showed no sign of relaxing a ban on processing migrant asylum petitions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Imposed by the former Trump administration, the policy, called Title 42, has continued under the Biden administration with an exception for unaccompanied minors.

The day after a cold rain had soaked the camp and forced classes to be canceled, Larisa Michel Flories kicked off her lower-level Spanish class by speaking into a bullhorn. A former staffer of a Honduras-based NGO that counsels children at risk of criminal involvement, she now lives in the border camp where hundreds of blankets and clothes hung to drip dry after the deluge.

“How was yesterday?” she asked her class cheerfully.

“Bad,” more than 50 kids shouted back.

But without the school and the rudimentary instruction it provides, the responses might have been worse.