A U.N. agency tapped to run new migrant centers around the Mediterranean says the plan won't solve the European Union's immigration challenge.

Irregular migration across the sea has been dramatically reduced; only about 45,000 people have made it to Europe that way this year. But the hot-button issue is driving the EU's political agenda.

Last week, EU states agreed to tighten their external borders and spend more in the Middle East and North Africa to bring down the number of arrivals.

Chancellor Angela Merkel, trying to save her coalition, on Monday agreed to set up migrant camps on the German border, highlighting how the EU is unable to agree on joint migration policies and how governments increasingly go it alone.

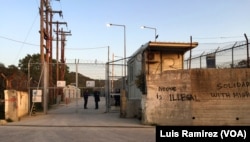

One thing EU leaders have agreed is to look at setting up "disembarkation platforms" to handle those rescued from the dangerous crossing. Most are brought ashore in Italy, but more than 1,300 people perished this year.

'Responsibility to govern'

"The Mediterranean is a shared space, north-south. We have a joint responsibility to govern what happens in that space, including avoiding that people drown," Eugenio Ambrosi, the head of the International Organization for Migration's EU mission, told Reuters.

The IOM and its sister U.N. agency for refugees, the UNHCR, would run the new sites.

Ambrosi said 10 existing migrant centers in Greece and Italy could first be beefed up and new ones could then be added in Malta. But opening others on the southern rim of the Mediterranean, as some EU states want, would take time.

"Before going outside of Europe, asking other countries to help, we have to make sure that enough European countries help each other," Ambrosi said in an interview.

Eventually, depending on where in the Mediterranean they were rescued, people would be taken to EU or African centers.

The much-publicized idea of Mediterranean camps would work only if more legal ways to get to Europe from non-EU countries are opened up, Ambrosi said.

Some deny admission

EU states would have to share legitimate asylum-seekers from the centers, an idea that has divided them bitterly since 2015. As more than a million people entered the EU in 2015, overwhelming Italy, Greece and Germany, eastern nations led by Poland and Hungary refused to help by taking in a share.

With this internal dispute still festering, the EU will turn to Tunisia and Morocco to host new sites. The African countries have a good opportunity to bargain hard.

Ambrosi said he opposed locating migrant centers in strife-torn Libya and said populists in the EU had failed to recognize how far the number of arrivals had dropped since 2015.

"It's not a migration issue, it's a political and functioning-of-the-EU issue," he said. "There is no quick fix — there has never been."