A father and son, part of a family of seven who left the United States to join Islamic State in Syria, are back on U.S. soil, charged with supporting the terror group.

Emraan Ali, 53, and his 19-year-old son Jihad appeared in federal court in Florida on Tuesday, charged with material support violations.

According to court documents, the pair surrendered to the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) near Baghuz, Syria, in March 2019, as the terror group’s final stronghold collapsed.

Another minor son, identified only as I.M.A., was with them at the time, but U.S. officials have yet to comment on his whereabouts or those of other family members, including a sister who was married to a British IS fighter and had his child when she was just 15.

The criminal complaints filed with the court say Emraan and Jihad Ali began speaking voluntarily to FBI agents in August 2019, several months after their surrender.

The elder Ali, who is also a citizen of Trinidad and Tobago, told the agents he first became interested in traveling to Syria in late 2014, after his wife’s sister sent the family photos and videos showing how good life was in IS’s self-declared caliphate.

Ali said he made the decision to go in March 2015, taking his wife, Sulaimah, his son Jihad, who was just 14 at the time, and five other children.

Jihad Ali told the agents the family left from their home in Trinidad, traveling to Brazil and then to Turkey, before smuggling themselves into Syria.

Jihad Ali told agents that while he was excited to make the journey, he also felt he could not go against his father’s wishes.

He also said that he was reluctant to take part in IS military training after the family arrived in Syria because he did not want to be separated from his family, though he also described some of the training, involving machine guns, rocket-propelled grenade launchers and urban warfare as “cool.”

FBI agents said that Jihad Ali later bragged about his military exploits and those of his now 15-year-old brother, in a series of WhatsApp messages to his biological mother.

But Ali told agents he was exaggerating to impress other IS fighters. He claimed that while he did take part in several battles, including the battle for Baghuz, he never killed anyone.

Emran Ali, likewise, told the FBI he did almost no fighting for IS, saying he got a medical discharge after experiencing heart problems after going on his first and only raid.

Instead, Emraan Ali said he made a living doing construction work and other odd jobs for IS, including the procurement of weapons and cellphones, and facilitating money transfers.

It appears the elder Ali’s activities were enough for U.S. officials to pay attention.

In September 2018, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Ali as one of two key IS financiers working on behalf of fighters from the Caribbean.

“For several years, a number of citizens of Trinidad and Tobago in Syria received money transfers through Ali,” the department said at the time.

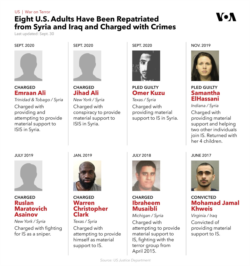

With Emraan and Jihad Ali back on U.S. soil, the U.S. has now repatriated at least 12 IS-affiliated adults and 10-IS affiliated children since 2017.

Earlier this month, 23-year-old Omer Kuzu, a Dallas, Texas, native, pleaded guilty of conspiring to provide material support to terrorism.

The fate of Kuzu’s wife and child, as well as that of his brother, remains unclear.

Mohamad Jamal Khweis of Virginia was convicted on terror charges and sentenced in October 2017.

Samantha Elhassani, pleaded guilty last November.

Charges against three others are pending. Two women who were repatriated last June have not been charged.

What to do with IS foreign fighters and their families has been a source of debate among the U.S. and its allies since the terror group’s caliphate collapsed.

The U.S. has long been pushing for countries to repatriate those who left to join IS, but many countries, especially those in Western Europe, have been reluctant to do so.

The SDF continues to hold about 2,000 foreign fighters in makeshift prisons in northeastern Syria. Another estimated 10,000 foreign women and children reside in displaced-persons camps in the region.