The Hassan Sham Camp, like so many others in Iraq, was built in 2016, as Iraqi and coalition forces retook territories held by the Islamic State terror group.

At least a million people fled their homes at the time and tens of thousands of men were arrested as IS suspects in the chaos.

In the years that followed, many were found guilty. Many were not. But here in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, hundreds of men who were acquitted or released after serving sentences for minor crimes are stuck in camps, with no way home.

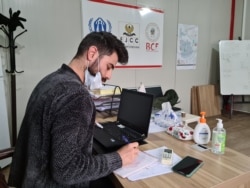

Mahmoud, 25, was arrested and accused of being involved with IS. After he had been detained for two years, authorities found him not guilty and let him go. But his release papers are not recognized outside the Kurdistan region, and if he tries to return to his home, he could be arrested again.

“I was released. I have a paper from the court of [the Kurdistan regional capital, Irbil] that proves my innocence,” he insisted, taking out the paper.

Other young men joked that a paper demonstrating acquittal in Irbil is worse than useless outside the Kurdistan region, encouraging Iraqi forces to make a quick arrest.

About 200 men are now living in Hassan Sham Camp under these circumstances, according to the camp manager, Mivan Akrey, and other camps across the region face the same problem.

The government of Baghdad does not recognize the decisions of Irbil courts in IS cases. And because the men were accused of serious crimes, they are ineligible for permits to move into towns and cities in the Kurdistan region.

“People here are bearing the cold and the extreme heat in these camps with limited humanitarian support,” he said at the camp on Monday, “simply because they cannot find security elsewhere.”

Camp closures

By most counts, roughly 2 million to 3 million people remain displaced from wars in Iraq. In the relative peace of recent years, the Iraqi government has decided to close many of these camps and says it will help people go home, or at least relocate.

“The return of the last family and the closure of the camps will end this file of displacement,” said Iraq’s Minister of Displacement and Migration Evan Faeq Jabro in a visit to the Hassan Sham Camp in July. The minister pledged support for departing families, including financial compensation for those returning to destroyed homes.

Since then, several camps have begun shutting down, and roughly 100,000 people are now “in limbo,” according to the Norwegian Refugee Council. Many people are now camping in abandoned buildings or on the outskirts of cities, towns and villages after leaving camps, the aid group added.

Some people cannot go home because their areas are still in rubble or are without basic services, like water or electricity. Others cannot cross checkpoints because of real or perceived past associations with IS.

“Closing camps before residents are willing or able to return to their homes does little to end the displacement crisis,” said Jan Egeland, the Norwegian Refugee Council’s secretary-general in a press release last week. “On the contrary, it keeps scores of displaced Iraqis trapped in this vicious cycle of displacement, leaving them more vulnerable than ever, especially in the middle of a raging pandemic.”

For Mahmoud, the idea of closing the Hassan Sham Camp now is difficult to imagine. With no legal solution in sight, he said, he is trying to make the desert camp livable.

In recent months, Mahmoud married a woman he met in the camp, and his mother has moved from their village into his tent.

“I was sick from loneliness,” he explained. “But everything changes when your family is with you.”

Stigma

Twenty-one-year-old Mohammad was in ninth grade when he fled the war with IS militants in the oil-rich city of Kirkuk.

Three weeks later, he was arrested and later transferred to a juvenile prison in the Kurdistan region. Then one day, after 5½ months of detention, he was released without ceremony.

“The officers said I was free, and that they hoped this misunderstanding would not happen again,” he explained. “They said, ‘Take care of yourself. Try to go back to school and live a good life. There is no longer a warrant for you.’ ”

He soon found out this was impossible. His brother was also released and attempted to go home, only to be arrested and sentenced to 15 years for a crime for which he had already been acquitted.

In the camp, there is no school, no work and no way to build a future.

And the longer the situation goes on, Mohammad said, the more dangerous it gets to attempt to travel. Stigma surrounding people who remain in camps is growing, he explained.

“If they closed the camps, people will be killed,” Mohammad said. “At the first checkpoint they will ask, ‘Where are you coming from? Why were you living in a camp all this time?’

“‘They will say, ‘Only IS lives in camps nowadays.’ ”