Researchers have devised a way to generate electricity using raw sewage and special bacteria.

Engineers at Stanford University call the invention a “microbial battery” and hope one day the technology will be suitable for use at sewage treatment plants.

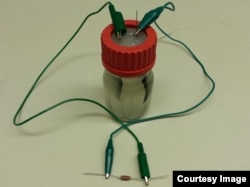

For now, the prototype is about the size of a D-cell battery and looks like a “chemistry experiment with two electrodes, one positive, the other negative, plunged into a bottle of wastewater.”

Inside that murky vial, attached to the negative electrode like barnacles to a ship's hull, an unusual type of bacteria feast on particles of organic waste and produce electricity that is captured by the battery's positive electrode.

"We call it fishing for electrons," said Craig Criddle, a professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering.

The electrons come from exoelectrogenic microbes – organisms that evolved in airless environments and developed the ability to react with oxide minerals, rather than breathe oxygen as we do, to convert organic nutrients into biological fuel.

For years, scientists have tried to tap the energy produced by these creatures, but until now it has proved challenging.

The Stanford researchers approach was new.

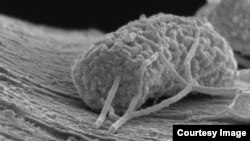

At the battery's negative electrode, colonies of wired microbes cling to carbon filaments that serve as efficient electrical conductors.

"You can see that the microbes make nanowires to dump off their excess electrons," Criddle said. To put the images into perspective, about 100 of these microbes could fit, side by side, in the width of a human hair.

As these microbes ingest organic matter and convert it into biological fuel, their excess electrons flow into the carbon filaments, and across to the positive electrode, which is made of silver oxide, a material that attracts electrons.

The electrons flowing to the positive node gradually reduce the silver oxide to silver, storing the spare electrons in the process.

According to Xing Xie, an interdisciplinary researcher, after a day or so the positive electrode has absorbed a full load of electrons and has largely been converted into silver.

At that point it is removed from the battery and re-oxidized back to silver oxide, releasing the stored electrons.

The battery, scientists say, is about 30 percent efficient in extracting the energy from waste water. While that may sound small, it is roughly the same efficiency as the best commercially available solar cells.

And while waste water will never offer the same potential solar energy could, the Stanford researchers say it’s worth pursuing because at the very least, it could offset some of the electricity used to treat sewage, or about 3 percent of the total electrical load in developed nations.

One drawback with the battery is the expense of silver.

"We demonstrated the principle using silver oxide, but silver is too expensive for use at large scale," said Yi Cui, an associate professor of materials science and engineering.

"Though the search is underway for a more practical material, finding a substitute will take time."

Engineers at Stanford University call the invention a “microbial battery” and hope one day the technology will be suitable for use at sewage treatment plants.

For now, the prototype is about the size of a D-cell battery and looks like a “chemistry experiment with two electrodes, one positive, the other negative, plunged into a bottle of wastewater.”

Inside that murky vial, attached to the negative electrode like barnacles to a ship's hull, an unusual type of bacteria feast on particles of organic waste and produce electricity that is captured by the battery's positive electrode.

"We call it fishing for electrons," said Craig Criddle, a professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering.

The electrons come from exoelectrogenic microbes – organisms that evolved in airless environments and developed the ability to react with oxide minerals, rather than breathe oxygen as we do, to convert organic nutrients into biological fuel.

For years, scientists have tried to tap the energy produced by these creatures, but until now it has proved challenging.

The Stanford researchers approach was new.

At the battery's negative electrode, colonies of wired microbes cling to carbon filaments that serve as efficient electrical conductors.

"You can see that the microbes make nanowires to dump off their excess electrons," Criddle said. To put the images into perspective, about 100 of these microbes could fit, side by side, in the width of a human hair.

As these microbes ingest organic matter and convert it into biological fuel, their excess electrons flow into the carbon filaments, and across to the positive electrode, which is made of silver oxide, a material that attracts electrons.

The electrons flowing to the positive node gradually reduce the silver oxide to silver, storing the spare electrons in the process.

According to Xing Xie, an interdisciplinary researcher, after a day or so the positive electrode has absorbed a full load of electrons and has largely been converted into silver.

At that point it is removed from the battery and re-oxidized back to silver oxide, releasing the stored electrons.

The battery, scientists say, is about 30 percent efficient in extracting the energy from waste water. While that may sound small, it is roughly the same efficiency as the best commercially available solar cells.

And while waste water will never offer the same potential solar energy could, the Stanford researchers say it’s worth pursuing because at the very least, it could offset some of the electricity used to treat sewage, or about 3 percent of the total electrical load in developed nations.

One drawback with the battery is the expense of silver.

"We demonstrated the principle using silver oxide, but silver is too expensive for use at large scale," said Yi Cui, an associate professor of materials science and engineering.

"Though the search is underway for a more practical material, finding a substitute will take time."