Merle Haggard, one of the most recognizable voices in American Country music, died Wednesday — his 79th birthday — at his home in Palo Cedro, California, following a months-long bout with double pneumonia.

Over the course of his career, Haggard released more than 80 albums, and 38 of his songs topped U.S. Country music charts, including “Hungry Eyes,” Momma Tried,” and “Okie from Muskogee,” which became an unintentional rallying cry of sorts against the hippie subculture during the late 1960s.

Haggard’s music centered primarily on his impoverished life growing up on the outskirts of Bakersfield, California. His gruff lyrics championing the hard life of blue-collar workers made him a favorite of working-class people across the country, but he infused his songs with more insight and tenderness than most

honky-tonkers. He also broadened the genre by writing about poverty, loneliness and social issues.

"Merle was one of the greats. He really embodied the Country music singer-songwriter," said Jay Orr of the Country Music Hall of Fame.

"He drew from his own experience, and he drew from the experience of working men and women in America. I think of a song like 'Working Man's Blues' which is a phrase that people use to describe Country music."

Haggard's sound drew from traditional Country but also touched on folk, pop, blues and rock. He referred to the improvisations of his band, the Strangers, as "Country jazz,'' and in 1980 he became the first Country artist to appear on the cover of the jazz magazine Downbeat.

Haggard's songs were covered by the likes of the Grateful Dead, Elvis Costello, Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Byrds, Emmylou Harris, Dwight Yoakam, Lucinda Williams and Reba McEntire.

"I can't remember when I haven't listened to him," said Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards. "Some of the best songs and best delivery you can get."

Along with his albums of original songs, he recorded tributes to such early influences as Country pioneer Jimmy Rodgers and Western swing king Bob Wills, and paired up with Willie Nelson and George Jones, among others. He also resisted the slick arrangements favored by some pop-Country stars.

"I'll tell you what the public likes more than anything,'' he told the Boston Globe in 1999. "It's the most rare commodity in the world — honesty.''

Distinctive voice

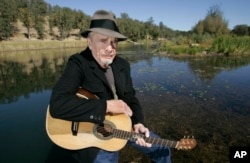

Haggard once said he preferred playing guitar to singing, but it was his voice that made him stand out.

"Haggard's exceptionally true intonation, his command of varied vocal textures and his insinuating phrasing would make him a superior vocalist in any idiom," The New York Times said of Haggard in his prime. "Like Muddy Waters in the blues field and only a handful of other performers, he both embodies and

transcends his rich American musical heritage."

He was born in 1937, the son of two Okies — Dust Bowl refugees from Oklahoma who moved west to escape the Great Depression and settled in Bakersfield. Haggard and his parents lived in an old railroad boxcar that his father, James Haggard, a railway worker, converted into their home.

Haggard, who was nine years old when his father died of a brain tumor, quit school in the eighth grade and began hopping freight trains. He also took up the guitar and petty crime and frequently was placed in — and escaped from — juvenile reformatories.

Later convicted of burglary — he had tried to break into a cafe but was too drunk to realize that at the time it was still open and serving customers — he served more than two years at the maximum-security state prison in San Quentin, near San Francisco, where he attended a concert for convicts by Johnny Cash, another legend in the world of American Country music, in 1958.

Haggard decided to turn his life around and try to build a career in music. (He was pardoned years later by California's governor at the time and a future U.S. president, Ronald Reagan.) He returned to his hometown in 1960 and, along with Buck Owens, helped define what became known as the "Bakersfield sound" — a more raw Country sound than the highly produced music that was coming out of Nashville at the time.

The subject matter of the songs Haggard wrote was more blunt than some of his fans were accustomed to — "Irma Jackson" was about interracial romance — and he rebelled when record company executives wanted to change his style.

"I've never been a guy that can do what people told me," he told the Times. "It's always been my nature to fight the system."

Haggard released his first independent album in 1963 and signed with Capitol Records in 1965, when he released his first number-one single, “I’m a Lonesome Figure.”

After that first success, one hit followed another and Haggard’s career soon attained epic proportions. Hits such as "Workin' Man Blues" and "If We

Make It Through December," the plaintive story of a laid-off factory worker trying to salvage Christmas for his young daughter, were likened to the populist works of Woody Guthrie.

Haggard's other hits included "Lonesome Fugitive," "Silver Wings," "Sing Me Back Home," "Daddy Frank (The Guitar Man)," "The Bottle Let Me Down," "The Fightin' Side of Me," "I Think I'll Just Stay Here and Drink" and "Pancho and Lefty," a duet with Nelson.

On the road

Haggard toured constantly with his band and once described his life as "a 35-year bus ride" — and that was in 1996, long before his bus stopped rolling.

Haggard's fame skyrocketed in 1970 with "Okie From Muskogee," an anti-hippie song ("we don't smoke marijuana in Muskogee, we don't take our trips on LSD") that came to be embraced by conservatives. Haggard said in interviews the song started out as a joke and a character study and that it did not necessarily reflect his views.

Haggard often told interviewers he was not political but his songs showed he was certainly opinionated and a libertarian thinker. In 2003, he defended the Dixie Chicks from fans' backlash after they criticized President George W. Bush, and he wrote a song in tribute to former first lady Hillary Clinton when she was seeking the presidency in 2007. Two years later he penned "Hopes Are High'' to commemorate Barack Obama's inauguration.

In "America First,'' he opposed the Iraq War, singing "Let's get out of Iraq, and get back on track.'' But he also wrote "Crippled Soldiers and Me" to protest the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said burning the American flag was an expression of free speech.

Stardom took a toll on the man known to his fans as "The Hag," and his career waned in the late 1980s amid personal problems. He filed for bankruptcy protection in 1992 after years of hard living, four divorces, gambling and bad investments. He once estimated that he had blown $100 million.

But by his mid-60s, Haggard had settled down and spent his spare time fishing on his ranch in Northern California. Musically, he remained as active as ever into his 70s, and received strong reviews for his 2010 album "I Am What I Am.''

Many musicians expressed their condolences and paid tribute to Haggard on Wednesday.

Country singer Carrie Underwood tweeted, "Merle was a pioneer...a true entertainer...a legend," while rock pioneer Jerry Lee Lewis said, "I will miss one of my best friends over all these years."

Longtime friend and frequent collaborator Willie Nelson told Entertainment Weekly, "He was my brother, my friend. I will miss him."

"We've lost one of the greatest writers and singers of all time. His heart was as tender as his love ballads,'' said Dolly Parton. "I loved him like a brother.''

Hall of Famer

Haggard once said in a PBS documentary. "I'm living proof that things go wrong in America, and I'm also living proof that things can go right." He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1994, the same year he won a Grammy for best male Country vocal performance in "That's the Way Love Goes.''

In 2008, Haggard underwent surgery to remove a tumor in his lung, but was back onstage performing within a few weeks. In February of this year, Haggard canceled a number of tour dates as he tried to recover from pneumonia, and he was unable to resume performing.

Haggard's son Ben, the Strangers' lead guitarist, said his father had predicted the day of his death.

"A week ago, Dad told us he was gonna pass on his birthday, and he wasn't wrong," Ben wrote on Facebook. "An hour ago he took his last breath surrounded by family and friends."

He lived his last years outside Redding with his fifth wife, Theresa Lane. He is also survived by his six children and his sister, Lillian Haggard Rea.

Some material for this report came from Reuters and AP.