Ice wedges are a particularly cool surface feature in the Arctic tundra. And new research suggests they are melting fast, which is bad news for the ecosystem at the top of the world — and the planet in general.

Ice wedges are formed when groundwater freezes, then — when the air gets cold enough at minus 17 degrees Celsius or lower — the ice begins to expand and contract, with more ice filling the cracks.

Eventually the wedge gets big enough to reach the surface, where it splits the earth like cracks in a sidewalk.

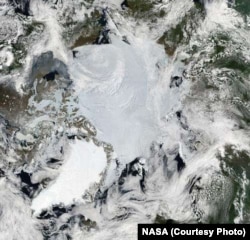

These ice wedges look like giant honeycombs on the frozen landscape. In the spring, the Arctic tundra looks like a jigsaw puzzle of small ponds with the ice wedges acting as the border between each little pond.

More carbon, more runoff

But new research published in this week's journal Nature Geoscience suggests these wedges play a significant role in maintaining huge stores of carbon dioxide held captive in the permafrost.

"The unique structure of ice wedge polygon landscapes promotes ponding of water and the accumulation of vast stores of soil carbon as wetland vegetation dies off seasonally and is buried and frozen over thousands of years" said Cathy Wilson, the Los Alamos National Laboratory geomorphologist who co-authored the paper.

While researchers have seen the collapse of ice wedges before, Wilson's study is the first to find that the rapid melting of ground ice has become widespread, with a ripple effect across the entire Arctic.

These collapses are called thermokarsts, and Wilson says they can change the area's hydrology by "creating a lot of new ponds, or by draining and drying polygon-shaped ponds by connecting them into a continuous drainage network."

The researchers also found that the melting ice wedges are speeding up the rate at which permafrost is thawing.

Permafrost is ground that has stayed frozen for at least two years. Most of the northern permafrost has been frozen for tens, or even hundreds, of thousands of years. It locks away season after season of plant life on ice, nearly 1,700 gigatons of organic carbon.

That's a whole lot more than all the greenhouse gas floating around our atmosphere in the form of methane and carbon dioxide, and it is released into the atmosphere as the permafrost thaws.

Tipping point

The scientists are concerned about the speed at which the arctic wedges and the permafrost are degrading.

"Change is happening so fast,” Wilson said. “I never thought I'd see thermokarst occur over the course of a few years at our field site. It's pretty exciting, but scary too."

The team noted that some of the wedge melting has occurred just from season to season, and in the case of one unusually warm summer, the surface wedges melted about 10 centimeters.

"It's really the tipping point for the hydrology," said the paper's lead author, Anna Liljedahl from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. "Instead of being absorbed by the tundra, the snowmelt water will run off into lakes and larger rivers. It really is a dramatic hydrologic change across the tundra landscape."

That change could release even more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, potentially speeding up climate change.