Driven from their homes in Syria, thousands of refugees in Lebanon are once again in search of shelter.

An estimated 8,000 to 12,000 refugees are on the move amid what is likely to be the biggest mass eviction of its kind in Lebanon since the war began.

The evictions, led by the Lebanese army and justified on the basis of security, have prompted concerns for the welfare of those affected, plunging them further into uncertainty and debt.

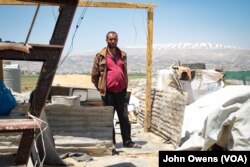

“What are you supposed to feel when you have settled and rested,” asked Hussein Muhammed Michel, “and someone comes and tells you that you have to move to another place?"

With the camp next to them now flattened, Michel, his wife and his four children are among those desperately searching for a new place to live. Their possessions are piled up outside the shelter that they have lovingly turned into a home in anticipation of the move.

About 330,000 Syrian refugees live in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, which borders their homeland. The Michels are among those unlucky enough to live in a camp close to Rayak airbase, the site believed to be the root cause of eviction notices.

The airbase has, according to local reports, recently been receiving American planes delivering military aid to the Lebanese army as it fights Islamic State on its borders and there are rumors the airbase could be expanded.

Many Syrians who spoke to VOA had not been told why they had to move. A spokesman for the Lebanese Army described the evictions as part of “normal regulations” before requesting an emailed inquiry for more specific details, an email that has not been responded to.

Piling debt

Whatever the reason, the need to move is piling on financial pressure for those already deeply in debt.

The family of Iman Hashem, who fled IS-held Raqqa a year ago, has managed to find a new camp to live in, but lost the $800 advance annual rent they paid at the start of the year in their previous site.

“This has affected me a lot and I became depressed,” she told VOA. “Where am I going to get the money to feed my children, my two little ones? How am I going to provide for them?”

According to Josep Zapater of the U.N. refugee agency the cost of moving can be between $600 to $1000, with the true financial impact felt far beyond these immediate expenses.

“If refugees are moving far ... they are going to lose jobs, so that going to have an impact on debt,” he said, explaining families then have to find ways of dealing with such debt.

“For quite a while we’ve seen problems relating to child work in difficult conditions, children six or seven years of age working and not going to school, while prostitution is also a problem in Bekaa.”

The eviction notices were first given at the end of March and about 4,000 people have so far moved, many to other camps in the region.

According to observers, evictions have so far been largely voluntary and peaceful, and some local mayors have allowed the displaced to settle anew.

But Zapater warned that such mass movements threatened to spark tensions between Syrians and Lebanese communities in a country that has felt the strain of hosting more than one million refugees, and seen political chatter from some quarters of returning Syrians to their homeland.

No contest

Syrians have no way of contesting such evictions.

The situation is all too familiar for Majid Muhammad, who is rebuilding his home, made mainly from wood and tarpaulin, in a new camp. Since fleeing the Syrian city of Aleppo for Lebanon four years ago he has been evicted from his home three times. For Mohammed, it is not just the financial burden that weighs heavily.

“It’s the strain, the strain on your self and your mind, having to go and sort out another place,” he explained. “Any decision the government has made, you are obliged to execute it, no matter what it is,” he adds.

With official camps not allowed in Lebanon, the UNHCR estimates 38 percent of refugees in the Bekaa region live in the informal camps that have been affected by the decision to clear Rayak.

In a separate incident in March, a mayor in the northern Lebanese town of Minyara threatened to evict refugees, citing the impact on infrastructure and demanding more financial aid.

“I have spoken to many refugees who have been forced from one location to another,” said Bassam Khawaja, a researcher for Human Rights Watch.

“Around 60-70 percent of Syrians don’t have [Lebanese] residency, and the consequence is a fear of going to the authorities to get past an eviction order - in fact, speaking to the authorities with legal status can result in backlash and arrest,” he added.

There is little sign that such evictions will stop.

“What can we do? ” asked Mohammed. “Hopefully our country will calm down, and then we can go home.”