The Afghan family expected by members of Kittamaqundi Community Church in the story below arrived Valentine's Day, February 14, after courts put a temporary stay on President Donald Trump's executive order banning refugees from Syria. When VOA contacted church members, the family was on their way from the airport to their new home, six days later than expected, but ready to start their new life.

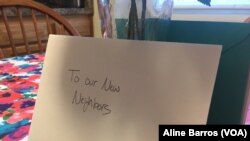

A “Welcome new neighbors” card sits on a kitchen table covered with a red, white and blue flowered tablecloth in a three-story townhouse in Columbia, Maryland. The living room is fully furnished, including a rocking chair. It is waiting for its family to come home.

The calendar in one room shows February 8 ... “because that’s the day they are still scheduled to arrive. … I mean, they won’t be arriving that day,” says Rev. Heather Kirk-Davidoff of Kittamaqundi Community Church, known as KC.

Kirk-Davidoff is the minister of the 100-member church that took on the resettlement of a refugee family from Afghanistan.

“Americans all over the whole country were [heart]broken by stories all over the news, especially in the summer in 2015, about people who were fleeing Syria and other areas in the Middle East, and dying in the Mediterranean as they try to cross,” Kirk-Davidoff said.

Her church started small, assembling welcome kits with household items for newly arrived immigrants.

Watch: Refugee Ban Leaves Resettlement Organizations in the Lurch

Small effort led to big one

That effort led to a contract with Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area, a nonprofit that partners with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to help legal immigrants start a new life through the refugee resettlement program.

Families who are assigned to a community or a church sponsor through the LSS Good Neighbor Program do not have family or other ties in the U.S.

All through December, KC members said they prayed to be assigned a refugee family.

But they also were very aware, Kirk-Davidoff said, of President Donald Trump’s campaign promise to curb the influx of refugees.

“So it became really a matter of urgency for us to get the family here to the United States before inauguration,” she said.

The Sunday before the new president was inaugurated, they were told a family was on the way.

House rented, furnished

With the support of five other faith communities, including a nearby mosque, the church rented a townhouse, raised $20,000, furnished the house with donated furniture, and assigned volunteers to meet the family at the airport and provide guidance on shopping, transportation and other local resources.

Members of the mosque donated a prayer rug and placed it in the home’s living room in the direction of Mecca.

KC members do not know much about the Afghan refugees except that the parents speak some English and have four kids: 11- and 6-year-old girls, and two boys — a 9-year-old and a 14-month-old baby who was born when the family was in a refugee camp after having fled their homeland.

“We really had this child [14-month-old] particularly in our minds,” Kirk-Davidoff said. “We figure this kid will only remember this house. He’s really the one whose life will start in the United States.”

Hopes dashed

But he and the rest of the family will not be moving into the carefully prepared townhouse in Columbia — at least not yet.

On January 27, Trump signed an executive order that barred all refugees from entry into the U.S. for 120 days. He said the action was needed to keep Americans safe from terrorism.

Even then, Kirk-Davidoff still had hope.

“We thought because the family at that point had a visa, had a date of entry. We actually celebrated that Sunday ... we felt we had made it,” she said.

But then reality set in.

“I was heartbroken,” church member Don Link said. He was the one who originally felt the call to this outreach mission.

“Some of us cried. We all prayed for our family. This is affecting us in our own hearts and our plans, but that’s nothing to what it is doing to the family. I just can’t imagine how these parents tell the kids that they are not coming to the U.S. How do they go forward?” he said.

Sense of loss

In the living room of the rented house, Kirk-Davidoff sits on one of the donated couches. She talks about the journey of six congregations with different religions that came together to welcome a family fleeing war and persecution. She fights to hold back tears, but her voice breaks.

“We don’t have a photograph of the family, but we have a picture of them in our minds’ eye. We have a sense of them walking in this home and finding a new life here. They had become very real for us,” she said.

Colin Richardson, an LSS case manager, said the organization does not get into politics, but is deeply saddened that tens of thousands of people may have lost their opportunity for a new beginning with a promise of freedom and prosperity.

“Over the next four months we will be concentrating on the families we have here. … And just waiting to see how things play out in the future of resettlement,” Richardson said.

According to LSS, 1 percent of refugees are resettled to a third country. The United States has been the world’s top resettlement country. In fiscal 2015, the organization and partners, like Kittamaqundi Community Church, helped more than 1,000 refugees.

Moving forward

In the meantime, stuffed animals sit on beds without children, the prayer rug lies beside the empty couch, and the welcome card on the kitchen table stays sealed.

Neither Richardson nor any of the volunteers knows where the family is now.

Link, however, is optimistic that he can somehow reach out to organizations overseas responsible for resettlement of refugees, to see if they can offer assistance.

“Somewhere there are people who have interacted with this family, whether it’s an NGO, the United Nations folks or State Department folks. We don’t know yet. [But] I’m hopeful,” he said.