On March 24 in Washington, D.C, an unexpected speaker at the March for Our Lives gun control rally arrested the crowd’s attention with a bold statement: “My grandfather had a dream that his four little children would not be judged by the color of their skin, but the content of their character,” said nine-year-old Yolanda Renee King. “I have a dream that enough is enough and that this should be a gun free world, period."

WATCH: Yolanda Renee King at the March For Our Lives

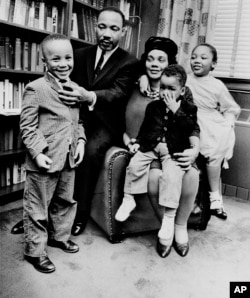

Young Yolanda — named for her aunt, Martin Luther King Jr.’s eldest daughter, who died of heart disease in 2007 — is the only grandchild of the late civil rights leader. Her father, Martin Luther King III, has carried on the work of the family, as have his two remaining siblings.

The late Yolanda King, an actress, gave an interview in the year 2000 about the pressures of being the child of Martin Luther King, Jr.

“As soon as people heard me speak, they would compare me to my father,” she said. “My siblings had the same kind of pressure. There was such a need, like they [King’s followers] were looking for a miracle."

“It was impossible to escape it, really,” she continued, speaking to a reporter for the Orlando Sun-Sentinel. “I found myself trying to be all things to all people. I felt a tremendous sense of responsibility and the pressure of expectation.”

The four siblings did not agree on everything. Yolanda King spoke out in favor of gay rights, while youngest daughter Bernice, a church pastor, spoke out against them. Martin Luther King III, like Bernice, stayed in Georgia. Dexter King, like Yolanda, moved to California.

All four King children have had positions of leadership at the King Center at one time or another, but none drew universal praise. The siblings have opposed each other in lawsuits over the fate of the King Center, the use of the funds generated there, and the future of precious objects owned by their father, such as his Bible. The siblings have also had to try to work with their father’s former colleagues.

Both Martin Luther King III and Bernice King have been elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the civil rights organization founded in 1957 and led by their father. But both struggled with the governing board over the direction of the group. Bernice King ended up turning down the job.

More work to do

Meanwhile, racial tensions in the United States are still depressingly high. The country elected a black president — twice — but white supremacist groups are growing bolder, both online and at demonstrations. There are repeated protests over white police killing black men — most recently, this past week in Sacramento, California.

So how should we assess the work of the King family business? Success? Failure? Work in progress?

The work is not finished, says Calvin Baker, a novelist and essayist who chronicles the African American experience in America.

“African Americans have always understood this to be a generation over generation struggle,” Baker said in emailed comments Tuesday. “Every black family is a part of it.” The fact of the Kings’ continued activism in the face of discouraging circumstances, he says, “tells as well on the Kings as it does poorly on the nation.”

“We are in another moment of great trouble, directly descended from our unwillingness to [defend racial equality] 50 years ago, or 40 years ago, or 100 years ago,” he says. “Will we have this same conversation fifty years hence?”

While that question remains unanswered, the three living King siblings seem to have arrived at an answer of their own: it’s time to pass the baton.

On Monday, they sat for an interview with CBS television, the first time the three have been interviewed together in more than a decade. Bernice King told interviewer Michelle Miller that despite family squabbles, the three are “very close.” Miller reported that former U.S. President Jimmy Carter encouraged the three to transition out of the work on their father’s legacy, or “get out of the family business.” While the specific reason was not divulged, all three children talked about their difficulties coming to terms with their father’s death. “All of us, to an extent, have not fully had the chance to grieve,” Dexter King told the interviewer. “I’m still working on it.”

Meanwhile, Martin Luther King Jr. has only one grandchild, the preternaturally composed nine-year-old who beamed as she quoted her grandfather’s most famous speech.

Yet as inspiring as she is, one more King family member is not enough, according to Baker. Lasting change, he says, needs to come from “a plurality of the people [who] are willing to embrace this as our shared legacy to fulfill . . . . for as long, and as many generations, as it takes.”