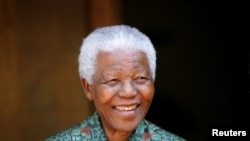

In her memoir, “Good Morning, Mr. Mandela,” Zelda la Grange, who worked for the late Nelson Mandela for nearly two decades, writes about her journey serving the man she called “Khulu” - the Xhoso word for grandfather.

La Grange, who served as the first black South African president's secretary, gatekeeper and close confidante takes readers from her awkward start to what she says became a bitter end within his inner circle during the final months of his life.

La Grange grew up in South Africa -- a white Afrikaner who supported the segregation of the races under apartheid. “We were, I suppose, racists,” she writes.

“I was a young Afrikaner girl whose views and mindset were changed by the greatest statesman of our time," Le Grance says, explaining how she got over her childhood racism to love the man she was once told was a “terrorist."

"Yet to me, he was more than my moral conscience. I had learned to care for him, because he cared for me. He shaped and changed my thinking because for him to employ a white Afrikaans-speaking young woman as his personal assistant was not only unprecedented, it was unheard of," she notes.

Melt Myburgh, the Afrikaans Commissioning Editor for Penguin South Africa, which published the book says the book sends a very important message in terms of Afrikaners and their place in the new South Africa.

"I think for many conservative Afrikaans speakers, or even white English speakers in the country, the book reminds us that there is a place for everybody in South Africa and that is the way Nelson Mandela wanted it to be," Myburgh says.

The bulk of the book focuses on Mandela’s life after his presidential term ended in 1999. La Grange paints an ugly picture of politics and family infighting. Neither The Mandela Foundation nor the government have issued public statements but Myburgh says the book is not intended to be anything but one woman’s recollections.

“There are some issues that come out in the book that are quite contentious or proved to be contentious. But it is an honest book about Zelda’s experience with Nelson Mandela," Myburgh says.

La Grange alleges that family power struggles and political interests compromised Nelson Mandela’s health as factions battled to control the former president's medical care.

The memoir goes further with la Grange recalling how Mandela’s wife, Graca Machel, was “emotionally brutalized” by one of his daughters and later sidelined with regards to making decisions about Mandela. In fact, la Grange says, Machel was forced to obtain a pass to attend Mandela’s memorial service due to hostility from some family members.

There were of course, better times. In one exceprt, la Grange recounts a visit to London to see the Queen, whom Mandela always greeted as “Elizabeth.”

“I think he was one of the very few people who called her by her first name and she seemed to be amused by it," la Grange writes. "When he was questioned one day by Mrs. Machel and told that it was not proper to call the Queen by her first name, he responded: ‘But she calls me Nelson.’ On one occasion when he saw her he said, ‘Oh Elizabeth, you’ve lost weight!’ Not something everybody gets to tell the Queen of England.”

Some of the book’s other anecdotes include a dinner with late Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, who was a staunch supporter of the African National Congress during the years of struggle against apartheid.

La Grange also recollects how Mandela referred to “this Bono chap” when referring to the U2 frontman. On meeting Brad Pitt, Mandela asked the actor for his business card, failing that, he asked Pitt what he did for a living.

Zelda la Grange’s book may not be a literary masterpiece but critics say it does offer a unique perspective on the liberation hero at close range. That alone, they say, makes the memoir stand out from the deluge of books on Mandela released since his death in December 2013.