When dinosaurs ruled the earth, life was tough for our mammalian ancestors. So they learned to hunker down during the day and venture out only in the relative safety of night. Scientists believe that this caused a sudden shift in the construction of their eyes from color vision to light detection.

In other words, dinosaurs caused mammals to develop night vision.

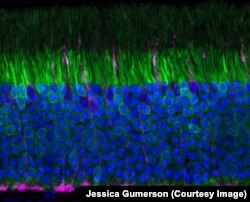

Mammalian eyes are different than those of amphibians, birds and fish because they are dominated by rods. Rods act like a black and white camera picking up subtle differences in brightness. The eyes of the other species are mostly cones, which detect color. During the age of dinosaurs, many species, including the first mammals, were active at night. When the eyes of our ancestors transformed from mostly cones to mostly rods -- and what caused the switch --are the main drivers behind centuries of work.

Transformer genes

The details of this switch are particularly important to researchers studying diseases that cause vision loss in humans, such as macular degeneration and Stargardt disease. Most of these diseases attack the rods in our eyes first, then move on to other cells in the retina, leading to permanent blindness. Although we have many more rods than cones in our eyes, we actually rely on the small number of cones to see. Understanding how these two structures form could lead to new ways to combat vision loss.

In a previous study, the lab of Anand Swaroop, a neurobiologist at the National Eye Institute, discovered that removing a specific gene kept rods from forming in the retina of mice. But if this gene is present in a cone, the cone turns into a rod. So this led Swaroop to supervise another study which isolated the rods and cones in newborn mice to observe which genes were present as they grew. “We were startled to find that in newborn rods there was some ... footprint of these ... cones.” Further research showed that cones start developing in the eye first and this gene turns most of them into rods.

But why does this gene exist and when did it start showing up in mammals? Swaroop's team enlisted the help of evolutionary biologists to look at sequenced genomes of 30 mammal and non-mammal species. The gene is present in the majority of mammals but is absent from non-mammals such as zebrafish. Since it is widely accepted that most dinosaurs were daytime hunters or foragers, mammals had to turn to the night to survive. The researcher suggest that coaxed this gene to acquire a new role, turning color vision cones to light detecting rods.

More than one way to know your past

But those researchers are missing a large component of the evolutionary record, according to paleontologists like Kenneth Angielczyk, at the Fields Museum in Chicago. In an email to VOA, he notes that without access to ancient DNA, paleontologists look at the size and shape of eye holes of synapsids - species that were ancestors to the first mammals. “But evidence [from] the fossils record suggests that change could have happened as long as 100 million years before the origin of modern mammal lineages,” Angielczyk explains.

The work of paleontologists shows the eye structure of most species indicates they spent most of their time in the dark. So this switch from cones to rods could have happened much earlier than the genetic information suggests it did. "It puts a boundary on by when it should have happened," says Christopher Heesy, professor of anatomy at Midwestern University, whose research focuses on the evolution of vision in mammals. But, he explains, it doesn't tell us when it first showed up.

Genetic information is only available for species that are not extinct so evolutionary biologists can only look back so far. “That’s the nature of evolutionary biology. We are always constrained by the species that are existing,” says David Plachetzki, evolutionary biologist and co-author of the study, which appears in the journal Cell. Based on the data available to them, they can say with confidence that the first mammals were converting their cones to rods to survive at night, at least as far back as when dinosaurs ruled the Earth.

Future transformations

But when that genetic mutation occurred in our ancestral lineage is not what has Swaroop excited. “If during evolution, cones became rods, can we make rods into cones? All we need is to keep some cones alive,” to reverse the effects of vision loss, he explained to VOA. Humans have more rods than they need so if some could be transformed into cones, they could slow down or even reverse vision loss.

The dinosaurs may not have forced our eyes to produce more rods than we need, but scientists are discovering how those extra cells can be useful to humans once again.