Mali’s griots - the traditional historians, story tellers, poets and musicians - say they have a role to play as the country struggles to heal from conflict. With negotiations ongoing in Algiers between northern separatist rebels and the Bamako government, famed singer Khaira Arby and her fellow griots think their country needs to have lasting peace.

When Mali was divided by the 2012-2013 Islamist occupation, Arby said, the country’s griots appealed to politicians to focus on reconciliation. Had the president accepted the griots’ offer to mediate, things might have taken a different turn, said the Timbuktu singer.

She said that while “many Malians feel their leaders have failed them,” despite this, her role is to promote forgiveness so that the north and the south of the country can reconcile and put the past behind them.

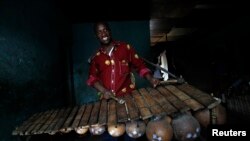

Traditionally, griots have been central in Malian society and throughout much of West Africa. They play prominent roles at baptisms, funerals and a Bamako wedding would not be complete without a griot.

But they are also the oral historians of the region, focusing on conflict resolution. They are often called upon to help make peace among feuding families and help to solve community problems. Arby said she promotes this message through her music.

“Music is a very effective way to get people to listen,” and, she said, “weddings are important not only for their cultural significance but to spread awareness.”

She notes weddings brings groups together - Tuareg, Songhai, Peuhl and Arabs - and all ethnic groups understand they are equally affected by the crisis in Mali.

Mali's northern desert region, home to the nomadic Tuaregs, has sought greater autonomy for decades. They last rose up in 2012, a rebellion that resulted in al-Qaida linked Islamists seizing the northern two-thirds of the country.

The Islamists imposed a violent form of Sharia, or Islamic law. Music was banned along with performances by griots. Arby fled south to Bamako and she only recently returned to her home in Timbuktu.

“The Islamists turned Timbuktu into a ghost town,” she said. “When you take away music, you take away the joy. Without music there’s no air, no life, especially in a country like Mali where music plays such an important role.”

Life in Bamako was difficult, she added. While the Islamist takeover didn’t affect the city directly, many northerners who had fled the extremists’ regime struggled to support their families. Musicians struggled to find work when clubs closed, public concerts were postponed and very few weddings took place.

“People still got married, but the weddings were more modest,” Arby said.

Many couldn’t afford to hire a griot.

More than a year after elections, reconciliation talks between the new government and former separatists remain in the fledgling stages. And as the French intervention force draws down, Malian troops and United Nations peacekeepers have not been able to provide the security needed as armed groups, jihadists and drug traffickers filter back into the vacuum in the north.

Arby, together with other prominent griots, such as musicians Bassekou Koyate and Toumani Diabate, continue to urge the government, the separatists scrambling for control of the north, and the population to reconcile.

“Without forgiveness, without reconciliation, there will be no peace. And I believe women play a key role in resolving conflict,” Arby said.

During the northern occupation, women were particularly targeted by the Islamists - facing beatings and arrest for not wearing a veil. Rape and forced marriages happened on a regular basis. The armed groups also enlisted children as fighters. Following the liberation of the north, women are speaking up about these abuses.

So Arby is calling on these women to take an active role in the peace process.

“Women should pass on the message of forgiveness to their children. If they share the same message, the men have no choice but to listen,” said Arby.

In Timbuktu the refugees are slowly returning. Women can walk in the streets without covering. Many Arab shopkeepers who fled during the French-led intervention have returned.

However recent months have seen an increase in violence against the U.N. peacekeeping force, MINUSMA, and hijackings of aid vehicles that has left many Timbuktu residents feeling unsafe. The town is still too dangerous for tourists and unemployment is widespread. Yet Arby is optimistic.

“A few days ago my family called me from Timbuktu. There was a marriage and over the phone I could hear the tam tam, the small drum played at weddings… Step by step peace is returning and life goes back to normal,” said Arby.

In Bamako the adored singer is back to work and back promoting a message of peace.