For extinct creatures like dinosaurs known only from fossils, it is notoriously difficult to differentiate the males from the females of a species because sex distinctions are rarely obvious from the skeletons.

But in the case of the well-known Jurassic dinosaur Stegosaurus, a study published Wednesday may provide a handy how-to guide on telling the boys from the girls based on the shape of the big, bony plates protruding from its back.

Stegosaurus, which roamed the western United States about 150 million years ago, was a large, four-legged plant-eater with two rows of plates along its back, as well as two pairs of spikes at the end of its tail for clobbering predators.

The largest Stegosaurus species reached about 30 feet (nine meters). The species in this study, Stegosaurus mjosi, measured roughly 21 feet (6.5 meters).

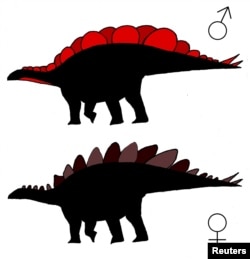

A Montana Stegosaurus "graveyard" contained fossils of several individuals, with plates coming in two distinct varieties: some wide, others tall. The wide ones reached sizes 45 percent larger in surface area than the taller ones, which were nearly 3 feet (90 cm) high.

"Males typically invest more into their ornamentation than do females, so the larger wide plates were likely from males," said Evan Saitta, 23, a paleontology graduate student at Britain's University of Bristol whose study appears in the journal PLOS ONE.

"The broad, thin structure of the plates and their positioning on the back of the animal suggest that they were used in sexual display, analogous to the tail of a peacock," Saitta said. "The broad, wide plates likely made a continuous display surface along the animal's back to attract mates, like a billboard."

To test whether the plate differences could instead be attributed to age, CT scans and microscopic analyses were performed that showed the bone tissue had ceased growing, meaning both varieties came from full-grown adults.

Anatomical and other differences between the sexes of a single species, like a male lion's mane or a male deer's antlers, are called sexual dimorphism.

Sexual dimorphism examples have been proposed in other dinosaurs, but many scientists have found them inconclusive. Saitta said the Stegosaurus plates might be "the most convincing evidence for sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs to date."

University of Bristol paleontologist Michael Benton added, "It suggests that many dinosaurs used sexual display, as birds and mammals do today, usually the males displaying or mock fighting to attract attention of females."