France’s youngest head of state since Napoleon Bonaparte presented himself as president of all the French Sunday as he was sworn into office in Paris, following in the Fifth Republic footsteps of political giants Gen. Charles De Gaulle and Jacques Chirac.

Much is riding on the 39-year-old Emmanuel Macron, who two years ago set out on what many dismissed as a Quixotic quest — to get himself elected to the French presidency as a centrist, pro-European Union candidate on his first ever political campaign and without the support of the country’s established parties.

Macron was greeted midmorning at the Élysée Palace by outgoing President Francois Hollande, who for many of the French exemplifies more than most of his predecessors the old saying that all political careers end in failure.

Macron has the reputation, reinforced by his election, as a man who always succeeds. Now he has the greatest of all challenges — to fulfill objectives even grander than those outlined by Hollande at his inauguration five years ago.

Just before Macron's arrival, Hollande stood on his office balcony taking one last sweeping glance from it of the palace grounds.

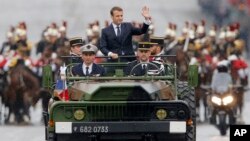

Amid the pomp and circumstance Sunday, future challenges were half-forgotten by the crowds lining the Champs-Élysées, where at the Arc de Triomph, Macron lay flowers at the memorial to the unknown soldier Inside the Élysée's ballroom earlier, Macron was presented with the grand collier de la Légion d'honneur once owned by Napoleon I. One of his supporters, Axelle Tessandier, a marketing consultant, tweeted “Émotion immense.”

But the task ahead wasn’t forgotten long. At his swearing-in ceremony, Macron, a former investment banker who served a mere two years as an appointed minister in Hollande’s government, told France his goal is to renew the Fifth Republic and to unify the French.

“The world needs what the French have always taught. For decades France has doubted herself,” he said. The world, and Europe, need France more than ever, he added.

“My mandate will give the French back the confidence to believe in themselves.” He said he would convince the people that "the power of France is not declining - that we are on the brink of a great renaissance.”

Unifying France will be a tall order. Twenty-one million people voted for Macron in the second round of the elections, but 12 million backed far-right nationalist Marine Le Pen, despite her lackluster campaign. Millions more didn’t turn up at the polling stations. And four million destroyed their ballot papers as a sign of disapproval of both candidates, the largest number ever to do so in a French election.

Having set himself the monumental tasks of trying to expand the center, and of convincing half the country which disapproves of EU membership that the European bloc is something to be valued, Macron has the immediate challenge of securing a parliamentary majority to back him.

He can do that either by leading his one-year-old En Marche! Movement -- renamed last week République en marche — to victory in parliamentary elections next month, or by cobbling together a center coalition. Polls suggest he might be able to pull off a parliamentary victory, one as unthinkable as his presidential win, and secure, a majority in the 577-seat lower house. Much will depend on who he names Monday as his initial prime minister.

If his party fails to win the majority of seats, the alternative would be La Cohabitation with a prime minister from an opposing political party, something the Fifth Republic has seen three times since 1958. La Cohabitation, analysts agree, would likely spell major trouble for Macron’s highly ambitious policy program. Macron wants to cut public spending and reorder a rigid labor market to allow businesses to hire and fire more easily, all in a bid to revive a stagnant economy.

At the same he says he wants to ameliorate the downsides of globalization for those left behind.

One of Macron’s rivals for the presidency, the conservative Republican Francois Fillon warned during the first round of presidential voting that Macron in office would be forced to “cook up parliamentary dishes of impotence and compromises.” Grubby legislative deal-making risks fueling public disillusionment with government — paving the way, some fear, for a Le Pen victory in five years time and a defeat of Macron’s aim to turn the French away from the extremes of left or right.

Meeting with Merkel

On Monday, France’s new President will endure his first rite of passage — a flight to Berlin to meet German Chancellor Angela Merkel. On his election, Merkel acknowledged the expectations many Europeans have of Macron, saying he carried “the hopes of millions of French people and also many in Germany and across Europe.”

He’s likely to enjoy smoother relations with Merkel than Hollande. He has been courting assiduously German leaders the past two years. He intends to push for closer cooperation between EU members as well greater centralization of the countries in the eurozone with the creation of a budget.

But he won’t please EU federalists in Brussels by likely also arguing the bloc has to be more flexible and in the recent words of Jean Pisani-Ferry, his chief economic adviser, recognize that “the governance of the eurozone remains excessively cumbersome and technocratic.”

Macron has talked tough about Britain when it comes to Brexit, but his approach will likely be shaped by Pisani-Ferry. In a policy paper last year for Bruegel, a think tank in Brussels, Macron’s aide argued the EU should use Brexit as a chance to shape a “Europe of two circles,” with the EU at its core and an outer circle of countries in a structured partnership.