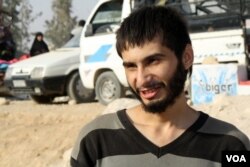

On Wednesday, 20-year-old Yazan Abdulrahman was released from detention after a 10-day investigation, cleared from any suspicion he fought with Islamic State militants. A few hours later, relaxed and smiling easily, he sat on dirty mattresses in a tent with his neighbors from Raqqa. Yazan then told VOA how he lost his family in an airstrike, escaped from IS and got a modicum of revenge on the militants that destroyed his city. He told his story in Arabic, and it is edited for clarity.

Before Daesh, we used to hang out in the gardens. We smoked nargila and played football. After they came, you couldn’t go out. It didn’t feel safe.

I call IS militants Daesh because they hated it. We first heard the term about a year ago on television. It sounded funny and it made them furious. We would whisper the word, but there were spies everywhere. The punishment was 180 lashes.

When I was in 11th grade, the schools closed so I got a job in a phone shop. Militants used to come into the store for help installing apps like Whatsapp. They looked terrifying with their long beards — like they had not showered in years.

iPhones and Android phones were banned from the beginning. They didn’t want anyone to have GPS signals on their phones. Last summer, Daesh banned all mobile phones and I lost my job.

After that I just stayed in the house until Oct. 3 this year. We saw a Daesh fighter climb onto the roof with an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade]. I heard the explosion and I remember seeing the room as I flew in the air, and then it was black. When I opened my eyes, all I could smell was smoke. An airstrike had hit the Daesh fighter on the roof.

My eyes were burnt and bloody, my hair was burnt and my leg was injured. My mother, my father and one of my brothers were dead. Twenty-three people were killed in the house that day, and in the house next door, the same explosion killed about 25.

A man who lived near by took me in and cared for me for a day and a half before I went back to find the bodies. When I got there, I saw destroyed houses had all been lit on fire and a Daesh fighter was guarding the charred rubble. I told him I was there to find the bodies of my family.

He said: “No, go out from here.”

Escape

From there, I went to a neighbor's house and after about a week and a half, Daesh was rounding up civilians to use as human shields. We all hid in the bathroom and locked the door.

Suddenly, someone knocked. I don’t know what time it was. We were all terrified.

It was Abu Hussien, a local drug store owner whose shop had been burned down. He told us Daesh was gone. We filed out of the house one by one, careful to stay in a line so that only the person in the front would be killed if we crossed a landmine.

We heard a voice say “Hey!” and we all froze. We thought it was Daesh and we craned our bodies to get a better look.

[You see, only a week before we had tried to flee. We were caught by a slim woman — veiled from head to toe — carrying a machine gun. “Go back!” she barked in a Moroccan dialect. We went back.]

"What is your name," I asked the man.

“My name is Abdulrahman Soyha,” he said.

I knew the name. My father had bought a car from his cousin, a well-known salesman. It was safe.

He told us to follow him to the Syrian Democratic Forces. From there, they brought us to this camp where I was arrested with other young men, and along with escaped Daesh fighters. I was terrified they would make a mistake. What if I looked like a Daesh on their list? What if one had my same name?

Prison

Civilian prisoners and the guys they thought were the real Daesh prisoners were held in separate rooms. We only saw them in a holding area while we were waiting to be interrogated.

They would make fun of the Daesh guys, and their Jihad “names.” One fighter referred to himself as Abu Dejana. The Syrian Democratic Forces called him Abu Dejaja — father of a female chicken.

Before one interrogation I saw the Daesh who was guarding my house after it was destroyed and burned. He denied being there, but I knew exactly who he was.

“Yes, I worked for the Caliphate State for one year and eight months,” he said, sounding proud. He was fat. They were eating fried chicken and rice while we were starving.

I couldn’t help myself and I attacked, pounding him with my fists until security forces pulled me off of him, saying, “There is no fighting here.”

It was misery for me. My family was dead and they burned their bodies. They wouldn’t let me bury them. It was too much.

No, I didn’t hurt him. I only got in two punches.