The end of the Korean War in 1953 did not end the hostilities between North and South Korea, or with the United States. U.S. administrations have been grappling with how to solve a problem like North Korea for decades.

In Seoul Friday, at a ceremony honoring the Korean War dead, General Walter Sharp, the commander of U.S. forces in Korea sounded a familiar call.

"True peace cannot exist when North Korea resorts to force and violence. Therefore we call on North Korea to cease its provocations and other aggressive acts."

General Sharp also warned that further provocations will be dealt with swiftly and decisively.

Seoul's accusation that North Korea sank one of its warships last March has again raised concerns about stability in the region.

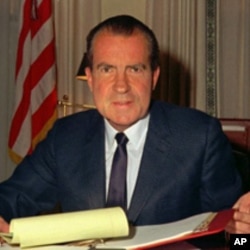

It is a familiar situation for Washington. In 1969, the North Korean military shot down a U.S. reconnaissance plane over the Sea of Japan, sending defense strategists scrambling to come up with a response. Recently declassified documents at the National Security Archive in Washington show that during that time, former U.S. President Richard Nixon considered full-scale war using tactical nuclear weapons.

President Nixon was quick to demonstrate America's presence in the region said Robert Wampler, a senior fellow at the National Security Archive.

"Nixon decided to resume reconnaissance flights, you know, more armed escort to in essence warn North Korea that if this happens again, the response will be much more severe," Wampler said.

The newly elected president and his key advisors, including National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, came up with at least two dozen plans targeting North Korea's military. One, code-named FRESH STORM, involved taking out Pyongyang's military air power. Another, code-named FREEDOM DROP, called for the select use of tactical nuclear weapons on command centers, air fields and naval bases.

Initial casualty estimates were modest, ranging from 100 to several thousand civilian deaths. But Nixon's team soon realized that striking North Korean targets could escalate into a bigger conflict than they wanted, said Wampler.

"In the end, it was always seen that the risk of setting off a broader conflict or even war always seemed to be greater than any possible benefit to be had."

Ultimately, President Nixon and his advisors took no military action, leaving diplomacy the only remaining option. It is a pattern repeated by U.S. presidents ever since.

After North Korea tested nuclear weapons in 2006 and 2009, analysts say U.S. war strategists debated whether to reign in the Pyongyang government with force. Instead, North Korea's provocations were addressed with sanctions at the U.N. Security Council.

Since then, said Wampler of George Washington University, military action has become even less likely because of North Korea's increased military strength.

North Korea says its nuclear program is a key defense against what it considers to be a hostile U.S. policy. It has pulled out of international nuclear talks and shown no indication of returning.

Despite the dramatic changes in world politics in the last 60 years, the standoff over North Korea appears frozen in time.