Long seen as an enclave for free speech in the region, Lebanon’s bustling and influential media landscape is facing an uncertain future.

Amid widespread reports of media outlets failing to pay their journalists, leading daily newspaper As-Safir announced it was closing at the end of last month.

Despite the decision being reversed shortly after, the news spawned editorials signaling the inexorable decline of the country’s newspaper industry.

It also sparked warnings of a “black day” for Lebanon should the country’s flagship titles go under from the country’s information minister, who reacted with a raft of proposals to prop up the tottering industry.

But amid the gloom, new voices are being heard and arguing that Lebanon’s relative freedoms deserve a better kind of journalism.

Not helped by heritage

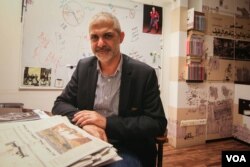

“Lebanese journalists helped establish much of the Arab media, and in the Gulf region most papers hosted Lebanese writers who helped spread the profession,” claimed Ahmad Salman, deputy general manager of As-Safir.

Salman spoke to VOA from an office decorated with headlines from the 42-year history of the paper.

“We were the only newspaper that published that day,” he said, pointing proudly to a front page from 1982, when Israeli forces attacked Beirut.

But history is not helping As Safir’s present-day finances.

In attempting to successfully respond to news consumption shifting online, As-Safir’s struggle is one faced by journalists across the world.

In Lebanon, however, strictly local problems are further stirring troubles.

Party power

Salman blames the paper’s decline on the country’s corruption and continual political stalemate, which he said had bred growing apathy and disinterest from readers.

But Ayman Mhanna, director of regional press freedom group SKeyes, told VOA that the main issue lies with who controls much of the country's press.

“Lebanon is a beacon is free speech, not free press,” he said.

“To say we have journalistic freedom is to imply a level of accountability and independence that doesn’t exist here.”

While meddling owners with political interests is a universal phenomenon, Mhanna said, in Lebanon “press are often either fully owned by political parties or kept afloat by political money.”

As well as driving divisive sectarian discourse and stifling criticism, this has stifled innovation.

“Money was always coming from political pockets,” he added, “so the need to be better was weak.”

As conflict rages in Syria and Yemen, that money appears to have diminished as the priorities of regional superpowers shift elsewhere.

Last week, for example, a Saudi-owned news station closed its Beirut office in what is being seen as the latest fallout from a recent stoking in Saudi-Iranian tensions.

Setting the agenda

But others feel that change is in the air – change for the good.

“The civil war paused media development,” said investigative reporter Habib Battah, referring to the series of conflicts from 1975 to 1990.

“People didn’t want to be confrontational afterwards. But that’s changing now. There’s growing willingness to confront power.”

Battah, who runs an independent news blog called The Beirut Report, pointed to the development in recent years of a vibrant grassroots activist movement prepared to “ask the right questions”.

Some mainstream outlets are now following their lead in challenging government decisions that would formerly have passed uncontested, he added.

The start of the country’s rubbish crisis last summer provided a crystallizing moment for activists in leading the news agenda, as the "You Stink" movement – which now has nearly 200,000 likes on Facebook - played a major role in feeding the slew of videos and reports bubbling up through social media.

“The audience of old-school papers owned by parties is dwindling, and some of these blogs are getting greater reach than mainstream TV channels,” Battah added.

As Kareem Chehayeb, the young co-founder of website Beirut Syndrome, puts it:

“Me and many of the youth are no longer buying into the rhetoric where other sects are being scapegoated.”

Fighting the odds

The jury remains out on whether such online communities and sites are financially viable in the long term and able to reach a genuinely diverse readership.

Meanwhile, there are suggestions aplenty for Information Minister Ramzi Joreige.

Some point to a French model, in which a Google-bankrolled fund offers cash to subsidize innovative media ideas, or call for the state-led consolidation of an oversaturated market.

Chehayeb believes “outdated” laws must be changed to embrace the work of independent journalist who he says currently have no legal protection from harassment and the security forces.

Back at the offices of As-Safir, which is not owned by a political party but is seen to be largely pro-Hezbollah, Salman struggles to muster hope for help from a government barely able to deal with a raft of other problems blighting the country.

Instead, the best he can do is try to fight the odds.

“Staying open is a gamble,” he said. “We might lose it all. But we might also find a way.”