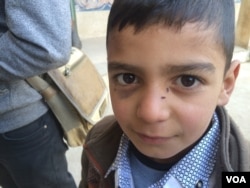

"My father was killed by the militants," says seven-year-old Mohammad, after wandering out of his schoolyard. "And IS didn't send me to school."

Mohammad meanders back through the gates, as other students study math and Arabic language in classrooms, without lights or heat. But bright pictures of balloons, numbers and animals decorate the walls.

Students say they are delighted to be back to school after three years at home, often not allowed to play outside because of the violence. By mid-February all students in eastern Mosul are expected to be attending school, and placement exams will determine their grade levels, according to Saab Ali, the school manager of the Al-Kufa boys' school.

Some students may have kept up with their learning at home, and will advance beyond the grade they left after IS took over in 2014, he says. Others will pick up where they left off, or go back to repeat grades.

"We are slowly coming back to life," explains Ali, while conducting a tour of the school.

All the windows, the water tanks and the bathrooms are recently repaired after being broken under IS and on one wall is a mural, depicting people practicing good sanitation. Like other pictures in Mosul, IS blocked out the people's faces with green paint, saying putting people's faces in art is sinful.

Every few minutes, the boom of outgoing mortar fire is heard, as IS is targeted in western Mosul. In the classroom, math students are asked if they are afraid of all the noise. "No!" they say almost unanimously, many of them smiling.

"They all know that's the Iraqi Army firing at IS to free all of Mosul," says Ali.

Children say they are not just happy to be going back to school because it gives them something to do. Resuming their education, they say, means once again being able to have dreams.

"I want to be a doctor because I want to cure sick people," says Mohammad's brother Omar, 11, grinning.

His smile fades as a teacher quietly tells us that Omar's father was a police officer, killed by IS like so many other members of Iraqi security forces.

IS traumatic ideology

Some teachers say the trauma the children experienced under IS goes deeper than the physical violence they witnessed and the people they lost.

Under IS rule, parents may have privately taught children that IS ideology, which aggrandizes violence and hate, is morally wrong. But publicly, residents did not insult IS, lest they risk imprisonment or death. Hearing both scorn and praise for the militant group can be confusing for children, says Ibrahim Ghanim, an Arabic language and Islamic studies teacher.

"Education is the key to ending Islamic State ideology," he adds. "It needs to start with opening schools and teaching them that IS ideology is wrong. We need to pay careful attention to education because years have been wasted."

In his neighborhood on Friday, schools had not yet opened and IS mortars continued to fall from the sky. Schoolbooks were not yet available, but Ghanim was still hoping his children will be prepared for the upcoming placement exams.

Thirty eastern Mosul schools are currently open and 16,000 children are attending, according to UNICEF. Other schools are being repaired after airstrikes, mortars or other attacks.

But as Iraqi forces prepare to attack IS in the west, locals say across the Tigris River families are not yet looking forward to schools opening. Instead, they are just trying to stay alive.

"We talk to our relatives in western Mosul secretly," says Mohammad, a baker. "On the other side, people are destroying their furniture to burn just to cook food. If anyone tries to escape, they are killed."

IS uses religion to justify killing fleeing families, he says. "They say, ‘You are going to a place of infidels, so you should die.'"