This month, the Pakistan government launched a door-to-door vaccination campaign against polio. It's the latest operation in the 20-year global fight against the crippling disease.

While polio cases have decreased by 99 percent worldwide over the past two decades, Pakistan is among the few countries - including India, Afghanistan and Nigeria - where polio remains endemic. American Ellyn Ogden's leadership of the USAID Polio Program has been key in efforts to eradicate the disease.

Getting started

Ogden's father was a business executive who moved the family with his job every two years. That lifestyle suited Ogden.

"For me it was exciting because I would get bored if I knew a place too well," she says. "So I was always looking forward to the next and meeting new people and seeing a new place."

It was a state of mind that set the tone for her future. Ogden went to Tulane University in New Orleans, majoring in international relations and pre-med. Instead of becoming a doctor, as her parents had hoped, she stayed at Tulane for a graduate degree in public health. She also gained valuable clinical skills working in hospitals at the same time.

"I spent a year as a nursing assistant. I worked in the laboratory taking blood samples and seeing how laboratory diagnostics work. I worked in cardiac care."

Gaining experience

What Ogden lacked was field experience. So, she and her husband, who she met in graduate school, joined the Peace Corps. They were assigned to Papua New Guinea in 1987. For two years she ran a provincial disease control program for 80,000 people, managing on a limited budget, with scarce medical supplies and drugs.

"And so I ended up trying to work around some of those obstacles and reach out to women in particular through non-governmental groups, through smaller women's clubs," she says, "and try to provide information in a more sensitive way that would bring them in for services without setting them up to be ostracized by their community."

That experience taught her some valuable public health lessons that remain with her today. "Be flexible. Learn to live with ambiguity. Keep an open mind."

Targeting polio

After leaving the Peace Corps, Ogden continued to work on international public health projects.

In 1997, she took the reins of the USAID polio program, coordinating U.S. efforts with health institutions, governments, community-based groups and donors around the world. Ogden says great strides have been made since 1988, when the World Health Assembly targeted polio for eradication. The disease then was endemic in 125 countries.

"Now we are only in four countries that have never stopped polio: India, Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan, and a 99 percent reduction in cases and a huge restriction geographically of where the virus is located," she says.

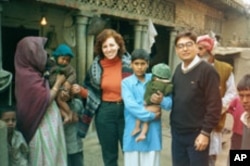

Ogden spends a lot time abroad. So much so that sometimes her husband and their two sons go with her. She manages large grants, attends mass immunizations, visits laboratories and supervises work in many countries. She says war is no excuse to stop immunization and uses well-honed diplomatic skills and technical know-how to forge ahead.

Finding solutions

In 2009, Ogden was honored with the USAID Award for Heroism.

"I was seen as a credible emissary to negotiate the Days of Tranquility in the eastern Congo among the main warring factions," says Ogden. "I had been discussing cease fires with some of the key forces in Angola when Jonas Savimbi was still there. And even today, I have an opportunity in Afghanistan to see where we can allow safe access and the vaccinators safe passage even though there is on-going conflict.

Ogden works in remote areas, in crowded urban centers and slums. Her first question, like the one she asked of textile workers at a dye pit in Nigeria, is always whether their children have been vaccinated.

"And they said, 'No. There's never been a vaccination team here,'" says Ogden. "And this is after almost 10 years of campaigns."

The children in that forgotten slum were vaccinated the next day.

Ogden cautions that the failure to eradicate polio would be detrimental to public health, not only in communities where polio still exists, but worldwide.

"Because if we can't get this simple 13-cent vaccine to all of the children in the world, how are we going to bring the more difficult things to them?"

Ogden says the fight to eradicate polio is one children of the world deserve. It would rescue four million lives over the next 20 years, she says, and it is our moral obligation to do so.