As rogue states and terrorist organizations continue to exploit cyberspace, governments around the globe must do more to curb illicit online funding, U.S lawmakers say.

"We really need to prioritize creating the cyber equivalent of the Geneva Conventions," Jim Himes, a Democratic representative from Connecticut and a member of the House Financial Services Committee's subcommittee on terrorism and illicit finance, said during a panel discussion Tuesday at the U.S. Institute of Peace in Washington.

"All of these problems get a lot easier if nation-states act responsibly," he added.

The United States and its allies are concerned that countries like Iran and North Korea and international terror organizations are developing sophisticated cyber capabilities to evade international sanctions and make money online.

Himes said the lack of global cooperation to counter illicit online funding could lead to intensified cyberwarfare between countries and continue the stream of revenues for terror groups like Islamic State.

IS was once the world's richest terror group, making millions of dollars from oil sales, ransom, extortion, taxes and other activities. As its physical caliphate crumbled and it lost the ability to generate revenue, the group has increasingly turned to the internet as an alternative financial source.

Cryptocurrency

Counterterrorism officials have reported dozens of pro-IS social media accounts on Twitter and Telegram that have asked supporters to fund the jihadists by sending funds in cryptocurrencies.

Last December, U.S. government officials said they charged a 27-year-old Long Island resident, Zoobia Shahnaz, with money laundering and bank fraud after she was found transferring $85,000 to support IS, with $62,700 of it in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

In February, Vasily Nebenzya, Russia's ambassador to the United Nations, accused IS members of seeking to fund their operations with online casinos.

There are national and international organizations who have been cracking down on terror financing, including the U.N.'s Working Group on Countering the Financing of Terrorism and the U.S.-led coalition's Counter IS Finance Group.

But officials said these efforts are often hindered by disagreement over mechanisms and lack of harmony between international law and domestic legislation.

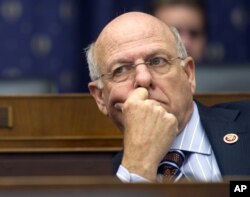

Steve Pearce, a U.S. Republican representative from New Mexico who also chairs the House Financial Services Committee's subcommittee on terrorism and illicit finance, charged that terror organizations and rogue states are getting better at misusing the innovative technologies, making it difficult for the international community to keep pace.

"The systems have to be very, very fast-moving, and I am not seeing that in the U.S. system and the world systems," Pearce told the audience at the peace institute. "The other side is making billions without risk. So, the stimulation for them to create problems is greater than ours to solve the problems."

Pearce said IS has been able to outsmart governments by selling ancient relics online and collecting revenues by exploiting legal platforms such as the crowdfunding website GoFundMe. At times, they have resorted to using the Hawala system.

"It [Hawala] is a legitimate forum of commerce, except it can easily be misused. Finding that misuse is extraordinarily difficult," Pearce said.

Hawala is an unregulated equivalent of Western Union and a common tool for transferring money in the Middle East; money is paid to an agent who then instructs a remote associate to pay the final recipient in a different country.

Citizen mobilization

Himes said an effective solution would ultimately require officials to mobilize citizens, especially in countries where debate about online privacy and encryption converge with cybersecurity and counterterrorism.

"I don't ever want somebody to crack strong encryption that is not us, because that means everything we do — our military, nuclear command and control — becomes observable to somebody who cracks strong encryption," Himes said.

"Citizens of the country need to think hard about what that means, and what they want us to do about it," he said. "If the government can crack strong encryption, there is no, theoretically, privacy anywhere, ever. So, what constraints do you want to put on that, or how much do you want us to keep up with our ability to use tools like that?"