Riga's Russian Theater stands as a testament to the endurance of Russian culture in Latvia, as well as a bridge between the two, despite political tensions.

"The theater is 135 years old. This is the oldest [Russian] theater beyond Russia. And within these 135 years it has quite harmoniously been incorporated into the context of Latvian culture," said the theater's director, Edward Cekhoval.

He shows visiting journalists the awards he has received from the Latvian government, as well as the Order of Friendship from Russian President Vladimir Putin.

At a March performance of Russian poet and writer Mikhail Lermontov's Princess Mary, Latvian subtitles flash on a screen above the stage as the actors in period costume speak only Russian.

"There is no discrimination as far as the language is concerned or any other life aspect because the [Russian] people who live here, they should clearly realize that they live in a different country, that this is not Russia," said Cekhoval, who was himself born in Russia, but has lived in Latvia for 28 years.

"They should observe all the laws existing in this country. And naturally [that includes] the Law about the Language."

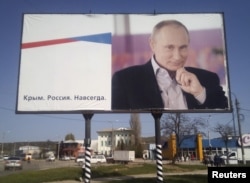

Russia justified its 2014 annexation of Crimea and its ongoing support for rebels in east Ukraine by claiming ethnic Russians there were threatened by nationalists, and faced discrimination because they spoke Russian. That raised alarm bells in the Baltics, where a quarter of the population in Estonia and Latvia, and about eight percent in Lithuania, are Russian, and where similar allegations of discrimination have been made.

Like Ukraine, many of the ethnic Russian minority in the Baltics are immigrants from when they were all part of the Soviet Union.

Occupier status

Since independence, though, Latvians openly call the Soviet Union an invader and occupier, along with Nazi Germany.

"The difference is that Germany has apologized and keeps on apologizing," said Gunars Nagels, director of the Occupation of Latvia Museum. "We often see in our guest book, people have written in German that they are sorry, after seeing all this. However, Russia does not consider all of this to have been something bad."

Soviet persecution and forced relocations controlled local populations through fear and intimidation that can still be felt at the former KGB offices in Riga called the Corner House. European tourists walk past open cell doors where political prisoners were crammed in small, dark spaces, many of them sent to prison camps or executed.

Critics say Russia is returning to Soviet fear tactics with its rhetoric about protecting ethnic Russians and its military posturing.

"Clear recognition of Soviet occupation and apology would be the right way how to gain some trust," said Latvia's foreign minister, Edgars Rinkevics.

Calls of discrimination

After independence in 1990, Latvia reasserted its culture with laws on citizenship that required a Latvian language test for the right to vote or to get a government job. Thousands of ethnic Russians were made "non-citizens" overnight.

Russia and Russian-Latvian critics call it discrimination, or even punishment for the Soviet past.

"It is a problem when in political life and it is a problem ... from Latvian society, actually," said IT worker Dmitry Prokopenko after showing a journalist his passport marked "alien."

Prokopenko learned Latvian in school, but he refuses to take the citizenship test on principle, arguing he shouldn't have to prove his proficiency to earn his civic rights.

"The living standards here in Latvia and in Estonia are much higher than in Russia," Rinkevics said. "Those Russian speakers are enjoying all the same freedoms that Latvian or Estonian citizens are enjoying."

Despite having ethnic Russian political parties, and an ethnic Russian mayor of Riga, some Russian-Latvian politicians claim the rights of non-citizens are being glossed over.

"They're not speaking about Russian education, they're not speaking about non-citizens, and so on. They're completely passive in these issues," said co-chair of the Latvian-Russian union, Miroslav Mitrofanov.

His party lost their seats in parliament in recent elections, and Mitrofanov says they now have go to Moscow for support.

"Because our voters here, they are consumers of this content produced in Russia," he said. "So, when we are speaking in Moscow, our people here in Latvia they say, 'Oh, guys, we have seen you. It is great that you are there among those politicians.'"

Rinkevics says Russia's influence in Baltic politics is nothing new.

"Guys, you are not used to it, in the United States or Germany or France," he said. "We are used to it. This is [a] concern. But, we also know how to tackle it. And we are ready also to share a little bit of our experience if asked with those countries that are very surprised that they [Russia] can be meddling in their election process through different means."

Looking to EU

Even the most critical Russian-Latvians still see the European Union as their future and look to Russia for their past and culture.

Mitrofanov laments that Russian propaganda portrays ethnic Russians in the Baltics as victims and the European Union as a failed project.

"And we do not agree with this. Because, Russia is not ready to support Latvia financially and the only source of existence of this country is the support which is provided by European Union," he said. "So, it's the main source of our stability nowadays."

And while Russian does not have the same status as Latvian, it is common in the city, and ethnic Russians make up about a quarter of the population.

"The unique feature of our geography and generally the position of the country gives a lot of choice to children," said Liudmila Smirnova, a Russian literature teacher at Riga Secondary School 40. "They may consider themselves Europeans to a greater extent because they study not only the language, but Russian literature and some Russian history. They have a chance to feel Russian."

VOA’s Ricardo Marquina Montanana contributed to this report.