Fifty years ago, in signing the Voting Rights Act of 1965, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson called it "one of the most monumental laws in the entire history of American freedom.”

Culminating decades of civil unrest and bloodshed, it banned discrimination based on a voter’s race or skin color and also required states with histories of entrenched racial barriers to obtain federal approval before altering any election procedures. Though African-Americans already had the constitutional right to vote, the legislation provided the federal enforcement to eliminate legal obstacles thrown up by some states and counties.

"Millions of Americans are denied the right to vote because of their color," the president said in his remarks August 6, 1965. He pledged that with this law, the federal government "will not turn aside until Americans of every race and color and origin in this country have the same right as all others to share in the process of democracy."

Since then, U.S. voting rolls have added millions of African-Americans, Latinos, Asian-Americans and others. Americans have voted an increasing number of minorities into public office and have chosen a black man for the nation’s highest elective office – twice. Many states have broadened access to balloting, from improving ease of registration to expanding polling times and absentee voting.

Under siege

But some observers, particularly Democrats, see a Voting Rights Act under siege.

"Across the country, there is a deliberate, systematic attempt to make it harder and more difficult for the disabled, students, seniors, minorities, poor and rural voters to participate in the democratic process," contends U.S. Representative John Lewis, a Georgia Democrat who as a young man was wounded in a 1965 march credited with hastening the voting law’s approval. "The burden should not be placed on citizens whose rights are violated to mount their own defense."

Watch related video report by VOA's Chris Simkins:

In 2011, "a record number of restrictions were introduced in state legislatures nationwide, including photo ID requirements, cuts to early voting and restrictions to voter registration," according to an American Civil Liberties Union timeline. "Many of these states have histories of voter discrimination and are covered under the VRA."

Legislative activity accelerated

States have been tinkering with their voting laws especially since the drawn-out, narrowly decided presidential race of 2000, said Wendy Underhill, who manages the bipartisan National Conference of State Legislatures' election laws section. "States are the laboratories of democracy" and legitimately can make adjustments, she said, adding that, though states have autonomy, they can't violate federal law.

Attention to those changes heightened in June 2013, when the Supreme Court struck down a key VRA enforcement provision that required nine states with histories of flagrant racial discrimination to get federal approval before changing election procedures. The justices’ ruling, by a 5-to-4 vote, found that the "preclearance" formula used on these mostly Southern jurisdictions was outdated.

"Our country has changed," Chief Justice John Roberts wrote on behalf of the majority, "and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions."

Leo Smith, the Georgia GOP's director of minority engagement, applauds the decision for ending what he considers to be unfair, unevenly applied oversight.

"Supporting the removal of restrictive laws is a freeing and liberating thing and we can only be benefited by that," he told VOA in June.

North Carolina in spotlight

A month after the ruling, North Carolina – formerly subjected to preclearance – enacted a combination of new rules that rolled back efforts to make voting more accessible and convenient.

House Bill 589 ended same-day voter registration, stopped preregistering 16- and 17-year-olds, and cut back early voting from 17 days to 10. That last measure eliminated voting on the final Sunday before the Tuesday election, a day often used by Democrats for "souls to the polls" voting drives in black churches.

The U.S. Justice Department and several civil rights groups challenged the new election law, with their respective lawsuits combined in a federal case heard in July in the former tobacco town of Winston-Salem. They said the Republican-sponsored legislation meant to deliberately disenfranchise many black, Hispanic and young voters, who tend to vote for Democrats.

But witnesses for the state testified that there was no discriminatory intent and that the voter turnout rate of African-Americans actually had increased in the 2014 midterms, after the new rules were in place, over 2010.

U.S. District Judge Thomas Schroeder is expected to issue his decision later this year. Because it may set precedent for the 2016 elections and beyond, the case is being closely watched – especially in states such as Florida, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin, where stricter voting laws have been contested.

Responding to Democratic critiques, the head of the Republican National Committee has said his party is embracing, not disenfranchising, minority voters.

Reince Priebus, in a recent op-ed, wrote that "a central part" of the committee’s "mission is to improve voter turnout, to encourage more Americans to make their voices heard and to engage young and new voters in the democratic process."

Uncomfortable reminders

In the flurry of voting restrictions, some see echoes of a grim history.

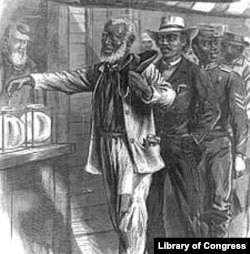

After the Civil War, the Constitution’s 13th Amendment abolished slavery and the 14th Amendment ensured citizenship rights. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, granted African-American men the right to vote. But some states and counties devised impediments.

Barriers were highest in the segregated South, with its history of slavery.

States "started to require things like literacy tests, instituting grandfather clauses, poll taxes, that kind of thing," said Andra Gillespie, a political scientist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. "... There were also changes to state constitutions in many Southern states that actually allowed for voting rights of blacks to be taken away on technicalities."

Blacks risked beating, whipping, lynching and other deadly force for daring to approach the polls. Atlanta's Southern Poverty Law Center counts 40 "civil rights martyrs" – including young bystanders and white civil rights activists – just from 1955 on.

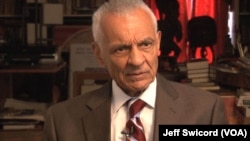

"We were murdered for [seeking] the right to vote," civil rights activist Cordy Tindell "C.T." Vivian told VOA on a hot June afternoon at his home in Atlanta, Georgia. "... We were beaten at night by policemen because they wanted to keep us under constraint."

A Baptist minister, he'd helped launch a Nashville affiliate of the Southern Christian Leadership Council in 1955 and was among the demonstrators in the civil rights movement's first march, in 1960 in the Tennessee city. He was working on the executive staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), at the behest of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., when in early 1965 he went to register voters in Selma, Alabama. Until then, only 2 percent of the city's eligible blacks had been able to sign up.

Vivian recalled confronting Sheriff Jim Clark, who proudly enforced local laws deterring Negros from registering and voting.

Clark, solidly built and armed with a nightstick, blocked Vivian on the Dallas County courthouse steps, the activist recalled. When the lawman turned to walk away, "I told him, 'You can turn your back on me, Sheriff Clark, but you can’t turn your back on justice.' So he decided to do what he always does and beat people.... He really, really hit me right across the face. And down I went."

The blow was so hard that the sheriff broke his own finger, he later said, contending Vivian provoked the beating by grabbing his nightstick.

Vivian sprang back up to show fellow protesters they shouldn't be intimidated for demanding their constitutional right, he said. He recalled telling Clark, "'We are willing to be beaten for democracy, and you misuse democracy in the streets.'"

A signal event

The civil rights movement reached a turning point March 7, 1965, a day that came to be known as Bloody Sunday. Some 600 voting rights supporters planned to march peacefully to Alabama’s state capital of Montgomery from Selma. But as they left Selma, the marchers encountered 150 state troopers and deputies at the Edmund Pettis Bridge.

"They came toward us, beating us with nightsticks, trampling us with horses, releasing the tear gas," recalled Congressman Lewis, who, as head of SNCC, helped organize the march. Then 25, he "was hit in the head by a state trooper with a night stick. I had a concussion at the bridge. I thought I was going to die."

Images of the attack, broadcast on television and splashed on news pages, horrified the nation.

Two days after the violence, before a second attempted march, King stopped at the hospital to encourage the injured Lewis. "'John, don't worry,'" the congressman recalled the civil rights leader saying. "'We [are] going to make it from Selma to Montgomery and the Voting Rights Act will be passed."

King's prediction came true: He and 2,000 others completed the march to Montgomery on a third try late that month. And the act became law roughly five months later.

Bills proposed

These days, Lewis is pushing to restore Voting Rights Act protections he said were "gutted" by the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision.

"If we fail or cannot repair the damage done to this act ... we will be less a democratic country, a democratic society," he told VOA last Wednesday in his House office, crammed with historic photos. One shows him at the White House with Johnson, hours before the president signed the 1965 law at the U.S. Capitol.

The next morning, he joined roughly 40 other Democratic lawmakers in front of the Capitol, where several took turns speaking at a podium adorned with a placard for a #RestoreTheVRA Twitter handle.

They urged House Republicans to bring to a floor discussion two measures focused on fortifying the Voting Rights Act, and they promised to campaign this summer to bring them to voters' attention. Lewis is a co-sponsor of both.

One is the bipartisan Voting Rights Amendment Act, proposed in 2013 and reintroduced this year by House members John Conyers, a Michigan Democrat who's the only sitting member of Congress to vote for the original law, and James Sensenbrenner, a conservative Wisconsin Republican who has been a key supporter for renewing the Voting Rights Act since the 1980s.

The other bill is the Voting Rights Advancement Act, whose lead sponsors are two Democrats. One is Representative Terri Sewell of Alabama, whose district is near Shelby County, the named plaintiff in the Supreme Court case.

"The challenge of Shelby to Congress was to find a modern-day formula," Sewell said in a phone interview.

The new measures offer updated criteria on the preclearance formula determining which states or jurisdictions should be subject to prior federal approval for election changes. Instead of looking at violations over a 40-year period, the proposed legislation would look at more recent infractions: over the last 15 years for the Amendment Act and 25 for the Advancement Act. With that and other criteria, four states immediately would qualify for preclearance under the Amendment Act; 13 would do so under the Advancement Act.

Just after the high court's ruling two years ago, Sensenbrenner joined Lewis in testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee. "Voter discrimination still exists," he said, "and our progress toward equality should not be mistaken for a final victory."

The House Judiciary Committee's chairman, Republican Bob Goodlatte of Virginia, has said it's not necessary to restore federal oversight of once-troubled jurisdictions. His state is one of the nine that had required preclearance.

"We are certainly willing to look at any new evidence of discrimination if there is a need to take any measures," he told the Roanoke Times in June. "But at this point in time, we have not seen that...."

But, according to USA Today, House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California said he would welcome committee debate on the preclearance provision.

Sewell said she and others owe a debt to all who worked toward passage and reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act over the years.

"We who are beneficiaries should play our part to help when we know there are vulnerable communities who are finding it hard" to access the vote, she said, calling that the most appropriate way to observe the law's anniversary.