This is Part 2 of a 5-part series: Africa's Endangered Peoples

Parts 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

For centuries, the Ogiek have made their homes deep in the Mau and Mount Elgon forests of western Kenya.

“The Ogiek look at forests in a different way. To them, there’s no better home. Forests have always provided the Ogiek with livelihoods, like they are some of the best beekeepers and honey harvesters in the world,” says Peter Kitelo, an Ogiek community leader who was born in the Mount Elgon forest.

Kiplangat Cheruyot, an Ogiek from the Mau forest and spokesman for the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program [OPDP] says, “Without the Mau forest, I believe that there could not be the existence of the Ogiek community. That’s where they get their clothing, that’s where they get their shelter. And without the Mau forest, it’s like a fish without being in the water.”

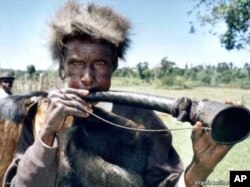

The Ogiek were once purely hunters and gatherers, dressing in the skins of the animals they killed for meat with bows and arrows, but they now also keep cattle and goats and grow vegetables.

“They also have a fantastic medicinal knowledge of a lot of forest plants,” says Fiona Watson, a researcher with Survival International, an organization advocating for the rights of indigenous peoples all over the world.

“So there’s this wonderful identification with the forests [but] much of that now is being stripped away and stolen from them,” says Watson, who’s spent a lot of time with the Ogiek.

Successive post-colonial governments in Kenya have tried to expel the Ogiek from their lands. Kitelo explains, “It was like, the Ogieks were destroying the forests and they had to get out of the forests. The government just doesn’t seem to understand Ogiek culture. For the state, a forest is for animals, not people, and anyone living in a forest is illegally there to poach wild animals.”

‘Fatal raids’

Kitelo says the Ogiek suffer regular “destructive and fatal raids” on their villages by “politically instigated criminals demanding land, the army, the police, and cattle rustlers.”

He’s survived a few of these attacks. He remembers one incident when “soldiers poured down” on his settlement, accusing the locals of stealing farmers’ cattle.

“It was a field day for them. Unfortunately they were not only going for cows, they were also killing [people] because the Ogiek were trying to defend themselves with bows and arrows and you could not go with a bow and arrow [against an automatic rifle],” Kitelo recalls.

In another attack, he says, “The government…came and burnt down houses, killed animals. They were saying, ‘This is a forest; you have to get out.’”

The Kenyan authorities confirm that state-sponsored “operations” have taken place in the forests but insist it’s to clear the areas of “criminal thugs” and not to “eliminate” the Ogiek.

In the latest incident in the Mau forest, Cheruyot says “assailants tried to kill” Ogiek land rights activist James Rana. “He was attacked at night by people with machetes and swords and knives. They destroyed his house and left him injured seriously,” says Cheruyot.

OPDP director Daniel Kobei says the “attempted murder was aimed in keeping Ogiek activists silent…. James has been at the forefront of fighting against injustices perpetrated against the Ogiek.”

Watson says “violent evictions” of Ogiek from their forests are sometimes caused by “neighboring, more powerful tribes, who are settled agriculturalists, who want to cut down the forests for [farm] land.”

The Ogiek ‘destroying’ the environment

The Kenyan government has repeatedly justified its attempts to evict the Ogiek from the forests on the grounds that the indigenous people are destroying “fragile ecosystems.”

Watson responds, “The Ogiek are the people who’ve conserved the forest by and large for centuries. So the very people whose forest it is, and who have looked after that forest as good guardians and stewards, are now being accused of destroying the forest and this is simply not true.”

Kitelo says his father, for example, was one of many tribal elders dedicated to planting indigenous trees. “It’s very strange because where they were going to plant trees [was] where the Kenya forest [department] was actually cutting down the indigenous trees and planting the exotic trees. This really tells you – the government has been more destructive than the Ogiek.”

Watson adds, “[Ogiek] lands have been progressively invaded, and the forests cut down, and this is now creating massive social problems and economic problems for the Ogiek and in fact for Kenya as a whole, because there are a number of rivers that have their source up in the Mau forest and they’re drying up because of this massive deforestation.”

In the recent past, says Watson, forest land confiscated from the Ogiek has not been conserved but rather turned into tea plantations and logging businesses by some “relatively high up” state officials.

Kenyan anti-corruption officials confirm they’re investigating a number of “illegal land grabs” in the forests, but Ogiek activists argue such cases have been “dragging” for years without any conclusions reached.

In the “absence of justice,” says Cheruyot, organizations representing the Ogiek have filed an urgent application at the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights for protection of themselves and their traditional territory.

The Kenyan government acknowledges that “mistakes” have been made in the past with regard to its environmental policies.

Watson indeed credits the Kenyan authorities with finally “waking up” to the fact that the forests represent a very important natural resource that they “simply have to save.”

Survival International has appealed to Kenya’s government to involve the Ogiek in efforts to conserve the forests. “Who better to do this than the people whose ancestral home it is, in whose interest it is to save this environment?” Watson asks.

Ogiek land ownership dilemma

Kitelo remains concerned that all Ogiek will eventually be driven from the forests because they don’t have official title deeds for the lands on which they’ve always lived.

“There’s really nothing they can stand with and say, ‘This is our ancestral land,’ because as far as the government records are concerned, it’s a forest and they must get out – not recognizing really that this is their land,” he says.

Cheruyot says “outsiders” now have official ownership of Ogiek land.

“So these people have the land, they have the title deeds. But the Ogiek is someone who is in the fields down there, in his ancestral home – he doesn’t know even what a title deed is, and then he’s…displaced from where he stays, so he becomes a squatter or a landless [person].”

The Ogiek are, however, encouraged by Kenya’s new constitution, promulgated last year.

“Our new constitution recognizes the rights of hunter gatherers. It recognizes the existence of ancestral lands; it recognizes the rights of minorities,” says Cheruyot. “The new constitution recognizes the need for Kenya to have a clean judiciary. We believe that if this happens, we Ogiek will finally get justice.”

Kitelo adds, “All we hope for now is that the authorities actually implement what’s written on the paper of the new constitution.”

Watson says, “The Kenyan government has been saying the right things, but it needs to be translated into action and they have to tackle the issue of indigenous land rights.… This is something that is recognized under international law. It’s also recognized by the United Nations Declaration on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples’ Rights.”

She says “time is of the essence, because unless the forest is protected, and unless the Ogiek have their land rights recognized, I can’t see how Kenya is going to tackle this massive issue of deforestation and illegal logging.”