Millions of Africans suffer from mental illness, but local superstition — and, some say, ignorance — can leave them undiagnosed and forced to suffer mistreatment and abuse.

That's why a new approach to counter the problem has been headquartered in Ngong, a town of in Kenya's Kajiado county, where a local initiative known as "Reason to Hope" is sending volunteers into surrounding villages teach people about psychiatric illness and identify those in need of care.

A recent visit to a Massai village in the north illustrated what the team is up against.

“Do you have any sick people here, people you think may be mad?” said one of the volunteers, who asked that his name be withheld.

No, said the local resident, allowing only that the village had had a history of "bewitched" individuals, and that one, a mad man, had recently died.

According to “Reason to Hope,” such exchanges are typical.

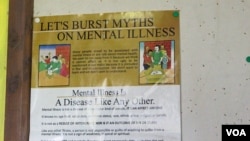

Launched by the Ngong-based Kenya Schizophrenia Foundation (KSF), the program raises awareness about mental illness.

“[People in some communities] still believe that mental health is not a sickness but something that can be dealt with by the community spirits, exorcism of demons and other things," says Reason for Hope Program Director Mary Wahome. "So for us, our main work is to let them know that it is an illness which, if treated well and given early intervention, can be managed.”

Working with rural health clinics, Reason for Hope has reached over 30,000 mentally ill people in rural areas all over Kenya.

For some clients, the intervention is life-altering.

“My mum is bipolar, by the way, and sometimes you think it’s that curse from the ancestors, especially if you come from the western region like I do," says 25-year-old Sheldon Moses, who was diagnosed with the disorder only after finishing high school. "Sometimes it’s alluded to that stuff but I think it’s also ignorance.”

Cost factor

Sheldon is covered under his parents' private health insurance, otherwise he couldn’t afford the medicine that controls his symptoms, which costs about $30 a week.

“It is seriously expensive and I am [wondering] if a policy can be put in [place] on how to take care of this, the way HIV/AIDS has been taken care of with [antiretroviral drugs] being brought in by ... USAID, which has chipped in and made it so much affordable to curb," he said. "I know it's not as much disastrous as how HIV/AIDS is, but if a program like that is to be done, it would really be helpful.”

Mainly funded by program members and outside supporters, KSF lakcs funding to cover regular treatment for all those in need.

But Wahome says dispelling myths and stigmas surrounding mental illness has made communities more proactive in caring for members who suffer.

“When the communities are aware, it is lifetime support [mental health sufferers] need, and the communities take over," she said. "We have places where the communities are very strong, where they are the ones who go for their own people, they know that in such a family there is this person. They get them medication. They even assist in cleaning them, they assist in helping them so we have seen the strength is through the communities.”

Still, she added, that effective treatments for psychiatric disorders do exist, she believes the government should help provide them to those in need.