An increase in Sino-foreign joint maritime research, particularly in the disputed South China Sea, is helping China improve its regional reputation by contributing to the health and utility of international waterways, analysts say.

China helped Malaysia with atmospheric studies on the high seas last year, among other marine science projects, the Southeast Asian country’s chief news service Bernama reported in December.

This month and next, China will work with the Philippines on exploring an underwater plateau, and Beijing’s official Xinhua News Agency said a vessel of Chinese scientists had reached port in Myanmar on Jan. 17 for joint oceanographic research.

Analysts say these cases, and others, let China and its partners find valuable marine resources while casting Beijing as a trustworthy steward of shared oceans in Asia.

Political will, funding

“This clearly shows there’s a political will of China, which means also it will influence, or it will strengthen its influence, in the region,” said Liu Nengye, senior lecturer at the University of Adelaide in Australia. “China is willing to pay for certain activities like joint marine scientific research. So as long as you pay, you somehow strengthen your influence in the region for sure.”

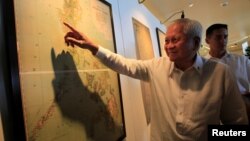

Beijing claims about 90 percent of the South China Sea, which covers 3.5 million square kilometers from Taiwan to Singapore.

Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam all contest China’s claims. They resent passage of Beijing’s coast guard vessels and its land-filling of small islets for military installations.

Science and marine protection

Since a world arbitration court ruled against the scope of China’s claim in mid-2016, Beijing has improved economic ties with other claimants to put the legal dispute behind them.

Those ties dovetail with China’s $900 billion Belt-and-Road initiative to build infrastructure in as many as 65 Eurasian countries to smooth trade.

Joint maritime projects are likely to focus on “low-sensitivity” issues popular with the Chinese partner nations, Liu said. All coastal states want to improve marine research on environmental protection, earthquake predictions, contamination from floating plastics and ocean acidification levels, he said.

Pollution persists because the South China Sea supports one-third of the world’s marine shipping traffic. Land reclamation as well as acidification also hurt coral. The harvests of an estimated 333,000 to 1.6 million fishing vessels have depleted stocks.

As a hint that China sees joint research as diplomacy, a year ago this month Xinhua said China and Vietnam would pursue “research of joint development” as a “transitional solution” to their sovereignty dispute.

In the past, China would do its own research, in some cases drawing protest, such as one from Brunei in 1992.

Two years ago Beijing’s State Oceanic Administration issued a “marine international cooperation framework plan” to run through 2020 covering the South China Sea as well as other Asian waters, state-run Chinese media say. The joint projects fall under this plan, Liu believes.

China is expected to bring better technology to research as scientists onshore develop a seaplane, drones for maritime use and an underwater observation network. A code of conduct being negotiated between China and a 10 member group of Southeast Asian countries would add to Beijing’s image offshore.

A stronger reputation for China would let the militarily and economically powerful country mute any protests as it keeps expanding at sea through land reclamation or military buildup. China cites historical documents as proof of its claims.

The deals as announced often lack specifics, such as who pays and what happens to any findings of value. The South China Sea is rich in fisheries, oil and natural gas.

Research in the Indian Ocean off Myanmar will include “comprehensive ocean observation to promote prevention and reduction of natural disasters,” Xinhua said without giving details.

Receptive but on guard

China’s partners are eager as long as they get a share of findings without compromising maritime sovereignty claims, analysts say.

The Philippines says it will have access to any discoveries, such as natural gas, on the plateau along its continental shelf.

Sino-Malaysian research last year took place mainly in the “internal waters” of Malaysia, the Bernama report said. The Chinese researchers must follow Malaysian laws and regulations, it said.

The ocean research paired with Chinese investment on land, such as in a $12.8 billion east-west railway line, are making China evermore familiar to Malaysians, said Ibrahim Suffian, program director with the Kuala Lumpur-based polling group Merdeka Center.

Bernama calls China’s maritime research with Malaysia a case of “soft diplomacy.”

“China is pretty much in the public radar now,” Suffian said. “I think for many people, particularly those in commerce and in the public sector, they are pretty much aware about the role of China.”

But China is likely to want something in return, some analysts say. The country often “dominates most projects” and is “not consultative enough with needs of local partners” overseas, said Alan Chong, associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

Expect Beijing to want favors in return, such as more infrastructure contracts, from Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, he said.

“China will lean on him, depending on how bold they want to be, either softly or not so softly to give them something in return for their financial backing,” Chong said.