A controversial plan by an Israeli political leader to annex parts of the occupied West Bank has triggered an angry debate in Israel, exposing serious divisions in the coalition government over the future of the peace process with the Palestinians.

This comes in wake of reconciliation between Palestinian political factions, which led to the breakdown of the latest round of peace talks. Israel has said it will not work with a government backed by Hamas, a designated terrorist organization, which runs the Gaza Strip.

“The Oslo era has ended,” Israel’s economy minister and Jewish Home party head Naftalie Bennett told Israeli and international experts who gathered for a security conference in the coastal Israeli town of Herzliya this week. He was referring to accords forged in Oslo in 1990s.

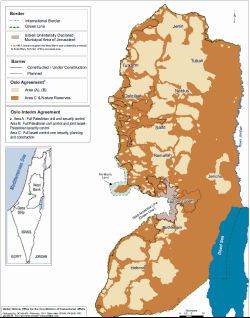

At that conference, Bennett re-introduced a “Security Plan,” first unveiled during his political campaign two years ago. The plan calls for Israel to gradually annex all of Area C, which comprises just over 60% of the West Bank and includes almost all of the controversial Jewish settlements.

The plan, which he referred to in his speech as a "sovereignty plan," would also offer citizenship to Area C’s Palestinian population, estimated at between 50,000 (Bennett’s figure) to 300,000 (the UN estimate).

“But if you choose, for your reasons, that you don’t want to be a citizen, that you want to be a resident, you’re still going to have a status,” Knesset insider and Jewish Home central committee member Jeremy Man Saltan said. “And we don’t want to leave anybody without a status in any areas that we are going to annex.”

The Bennett design would give Palestinians full autonomy over Areas A and B and allow for the free flow of people and goods between them via highways and bridges that would link the mostly non-contiguous zones.

“We don’t want to run their lives for them,” Bennett told his audience Sunday. “On the contrary, we want to upgrade all their infrastructure, their electricity, their transport. We want their lives to be better lives, because true peace only grows from below upwards.”

Bennett’s plan would give Israel control of east Jerusalem and the Jordan Valley east to the Dead Sea. It would not allow for the right of return of millions of Palestinian refugees and their descendants.

The 1995 Oslo II accord divided the West Bank into three administrative zones: Areas A, under full Palestinian civil and security control; Area B, under Palestinian civil control and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control, and C, under full Israeli civil and security control, until a final peace deal could be reached.

The Palestinians are holding out for a future state encompassing all of the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem as their future capital.

Reaction from the left

Yair Lapid, Israeli finance minister and leader of the centrist Yest Atid party, the second largest party in the coalition government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, slammed Bennett’s proposal in his own speech at Herzliya.

“If even one settlement is unilaterally annexed, Yesh Atid won’t just leave the government, it will topple it,” Lapid said.

He said the right wing in Israel is pushing his party into blaming Netanyahu for a rift with Washington and said a political settlement with the Palestinians should not be viewed merely as a “price” to be paid by Israelis, but something in their best political interests.

“We need to implement the two-state solution and to be separate from the Palestinians,” he said, expressing concerns over a growing Palestinian population that could someday threaten Israel’s national identity.

“This is not a marriage we are looking for,” he said. “We want a divorce settlement.”

Speaking at the same conference, Israeli Justice Minister and Hatnuah party leader Tzipi Livni said the settlements are a burden that is preventing Israel from reaching a peace deal with the Palestinians. She, too, threatened to leave the coalition if any settlements were annexed.

Responding to their speeches, foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman lashed out at Prime Minister Netanyahu for allowing so much “chaos” in a single government. And he demanded that Netanyahu come up with a single political plan to unite all the factions.

Palestinian view

“What’s wrong with this plan is pretty much everything,” said Yousef Munayyer, Executive Director of Washington, D.C.-based Jerusalem Fund.

“It’s a plan that starts from the point of view that Israel—and only Israel—gets to determine the future of these Palestinians living in occupied territory, and that they have no role or say in making their own future,” he said.

“It’s based on a colonialist notion that ‘our presence in the land is going to be welcomed by the natives because it’s going to improve their economic status and lift them up into civilization,’” he added.

In recent days, Netanyahu has said little on the issue except to criticize Lapid for political inexperience.

Indecisive or just stalling?

The Israeli prime minister has publicly endorsed a two-state agreement and blames the Palestinians for the stalemate in talks. Netanyahu’s critics, among them New York University professor and negotiation insider Alon Ben-Meir, say otherwise:

“What you have today is very right-wing Israeli government led by Netanyahu and supported by the Jewish Home, Naftali Bennett’s party, who are absolutely committed not to allow the creation of a Palestinian state,” said Ben-Meir, who has been directly involved in various negotiations between Israel and its neighboring countries such as Turkey.

“What that means is rejecting the unity government is only a political maneuver. But the reality is that with or without such government, Netanyahu is not willing to negotiate in earnest in order to resolve the conflict,” Ben-Meir said.

Other blame Netanyahu for being irresolute.

"Netanyahu has always preferred the option of 'do not do today what you can delay for as long as you can', an approach reflecting the sense that time is not necessarily working against Israel, and that the current situation, while not ideal, is the ‘devil you know,'" Israeli political analyst Josef Olmert said.

What is clear is that Netanyahu, by virtue of the makeup of his coalition, is in a political bind: If he opposes right-wing parliamentarians, who make up the majority of his coalition, and concedes to the Palestinians, it will mark the end of his tenure as prime minister.

If he endorses annexation he runs the risk of isolating Israel internationally, and some Israeli analysts fear that this could lead the U.S. and Europe to support a Palestinian appeal to the ICC.

The United States maintains that final status issues such as settlements, Jerusalem and the refugees may only be resolved through diplomatic negotiations.

The U.S., E.U., U.N. and China have said they will work with the new Palestinian government if it continues to adhere to the principle of peace with Israel based on a two-state solution.

This comes in wake of reconciliation between Palestinian political factions, which led to the breakdown of the latest round of peace talks. Israel has said it will not work with a government backed by Hamas, a designated terrorist organization, which runs the Gaza Strip.

“The Oslo era has ended,” Israel’s economy minister and Jewish Home party head Naftalie Bennett told Israeli and international experts who gathered for a security conference in the coastal Israeli town of Herzliya this week. He was referring to accords forged in Oslo in 1990s.

At that conference, Bennett re-introduced a “Security Plan,” first unveiled during his political campaign two years ago. The plan calls for Israel to gradually annex all of Area C, which comprises just over 60% of the West Bank and includes almost all of the controversial Jewish settlements.

The plan, which he referred to in his speech as a "sovereignty plan," would also offer citizenship to Area C’s Palestinian population, estimated at between 50,000 (Bennett’s figure) to 300,000 (the UN estimate).

“But if you choose, for your reasons, that you don’t want to be a citizen, that you want to be a resident, you’re still going to have a status,” Knesset insider and Jewish Home central committee member Jeremy Man Saltan said. “And we don’t want to leave anybody without a status in any areas that we are going to annex.”

The Bennett design would give Palestinians full autonomy over Areas A and B and allow for the free flow of people and goods between them via highways and bridges that would link the mostly non-contiguous zones.

“We don’t want to run their lives for them,” Bennett told his audience Sunday. “On the contrary, we want to upgrade all their infrastructure, their electricity, their transport. We want their lives to be better lives, because true peace only grows from below upwards.”

Bennett’s plan would give Israel control of east Jerusalem and the Jordan Valley east to the Dead Sea. It would not allow for the right of return of millions of Palestinian refugees and their descendants.

The 1995 Oslo II accord divided the West Bank into three administrative zones: Areas A, under full Palestinian civil and security control; Area B, under Palestinian civil control and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control, and C, under full Israeli civil and security control, until a final peace deal could be reached.

The Palestinians are holding out for a future state encompassing all of the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem as their future capital.

Reaction from the left

Yair Lapid, Israeli finance minister and leader of the centrist Yest Atid party, the second largest party in the coalition government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, slammed Bennett’s proposal in his own speech at Herzliya.

“If even one settlement is unilaterally annexed, Yesh Atid won’t just leave the government, it will topple it,” Lapid said.

He said the right wing in Israel is pushing his party into blaming Netanyahu for a rift with Washington and said a political settlement with the Palestinians should not be viewed merely as a “price” to be paid by Israelis, but something in their best political interests.

“We need to implement the two-state solution and to be separate from the Palestinians,” he said, expressing concerns over a growing Palestinian population that could someday threaten Israel’s national identity.

“This is not a marriage we are looking for,” he said. “We want a divorce settlement.”

Speaking at the same conference, Israeli Justice Minister and Hatnuah party leader Tzipi Livni said the settlements are a burden that is preventing Israel from reaching a peace deal with the Palestinians. She, too, threatened to leave the coalition if any settlements were annexed.

Responding to their speeches, foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman lashed out at Prime Minister Netanyahu for allowing so much “chaos” in a single government. And he demanded that Netanyahu come up with a single political plan to unite all the factions.

Palestinian view

“What’s wrong with this plan is pretty much everything,” said Yousef Munayyer, Executive Director of Washington, D.C.-based Jerusalem Fund.

“It’s a plan that starts from the point of view that Israel—and only Israel—gets to determine the future of these Palestinians living in occupied territory, and that they have no role or say in making their own future,” he said.

“It’s based on a colonialist notion that ‘our presence in the land is going to be welcomed by the natives because it’s going to improve their economic status and lift them up into civilization,’” he added.

In recent days, Netanyahu has said little on the issue except to criticize Lapid for political inexperience.

Indecisive or just stalling?

The Israeli prime minister has publicly endorsed a two-state agreement and blames the Palestinians for the stalemate in talks. Netanyahu’s critics, among them New York University professor and negotiation insider Alon Ben-Meir, say otherwise:

“What you have today is very right-wing Israeli government led by Netanyahu and supported by the Jewish Home, Naftali Bennett’s party, who are absolutely committed not to allow the creation of a Palestinian state,” said Ben-Meir, who has been directly involved in various negotiations between Israel and its neighboring countries such as Turkey.

“What that means is rejecting the unity government is only a political maneuver. But the reality is that with or without such government, Netanyahu is not willing to negotiate in earnest in order to resolve the conflict,” Ben-Meir said.

Other blame Netanyahu for being irresolute.

"Netanyahu has always preferred the option of 'do not do today what you can delay for as long as you can', an approach reflecting the sense that time is not necessarily working against Israel, and that the current situation, while not ideal, is the ‘devil you know,'" Israeli political analyst Josef Olmert said.

What is clear is that Netanyahu, by virtue of the makeup of his coalition, is in a political bind: If he opposes right-wing parliamentarians, who make up the majority of his coalition, and concedes to the Palestinians, it will mark the end of his tenure as prime minister.

If he endorses annexation he runs the risk of isolating Israel internationally, and some Israeli analysts fear that this could lead the U.S. and Europe to support a Palestinian appeal to the ICC.

The United States maintains that final status issues such as settlements, Jerusalem and the refugees may only be resolved through diplomatic negotiations.

The U.S., E.U., U.N. and China have said they will work with the new Palestinian government if it continues to adhere to the principle of peace with Israel based on a two-state solution.