The peshmerga general frowned when asked about a top Kurdish bomb-disposal expert killed last month the day after the assault on Mosul, Iraq began. “He was a very brave man,” said Gen. Mahmood Kakaye.

Suleman Sahed Chirukaya was trying to disarm a jihadist bomb in a tunnel near the town of Bashiqa, 24 kilometers from Mosul, one of hundreds he’d defused saving countless lives, when an anti-handling device triggered a blast, critically wounding him. Flown to Germany, where he’d lived a comfortable life for 16 years before returning to Kurdistan, he died in a hospital in Koblenz.

In a television interview, his brother, Salih, said Chirukaya felt he couldn’t just watch from afar the Kurds battling Islamic State, and re-joined the peshmerga early this year.

“Since July 2014, we have defused 14,000 Daesh bombs,” said Gen. Kakaye, who was using an Arabic term for IS. “Chirukaya was a real expert and we’ll miss him; he was a good man, but we have others and the work never stops,” said Kakaye, who oversees the peshmerga's bomb disposal teams.

Like U.S. troops after the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the peshmerga are finding the deadliest weapons being arrayed against them by the jihadists are IEDs and vehicle-borne bombs (VBIEDs). The peshmerga are updated regularly on the tell-tale signs of IEDs, but identifying the bombs is a moving art.

The jihadist bomb makers and the Kurdish bomb disposal teams are competing in a deadly cat-and-mouse game that favors the bombers.

The general wouldn’t disclose how many bomb disposal technicians the peshmerga have deployed, but he says large resources are devoted to battling the jihadist bomb makers, who have been manufacturing on a massive scale more sophisticated devices using civilian components and electronics as well as materiel ranging from cell phones and the parts of battery-operated toys to fertilizer and aluminum powder and pastes used in agriculture.

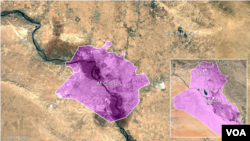

For two years, IS has been running a bomb manufacturing network of makeshift factories set up in towns and villages across their self-styled caliphate straddling Iraq and Syria.

Earlier this year, Conflict Armament Research, a London-based research organization that monitors the movement of conventional weapons and ammunition, warned, “IS forces have manufactured and deployed improvised explosive devices (IEDs) across the battlefield on a quasi-industrial scale.

Responsible for a large number of civilian and military casualties, these improvised bombs endanger and significantly delay ground operations against IS positions, while threatening the safe return of displaced populations. Made of components that are cheap and readily available, IEDs have become IS forces’ signature weapon.

Kakaye said, “They have refined their designs creating new types of IEDs ranging from suicide and car bombs to landmines, booby traps and improvised mortars, and they experiment where to plant their IEDs. There are the obvious places where IEDs can be found; opening a front door or a fridge door can trigger a blast; but, there are twists and they are ingenious in what they do,” he adds.

IEDs are planted in everything from food jars and cans to toys and clothes. They have been found in trash and in the carcasses of dead animals.

Iraqi security forces battling their way into Mosul and Shi’ite militias in the countryside are also suffering heavy losses from the IEDs.

When the peshmerga or Iraqi units manage to take ground, their first order of business is to clear remaining IEDs, and as they do so, they can come under attack from jihadists mounting ambushes and commando-style raids. That was seen in the battle for Bashiqa last week, when peshmerga were caught in a huge IED blast before coming under sustained IS gunfire.

Kakaye’s bomb disposal experts do not have the advantages of their counterparts in Western militaries - they don’t have modern blast-proof suits. Nor do they have motorized robots to help with the defusing of IEDs.

According to Conflict Armament Research, IS acquisition networks set about quickly to secure a steady flow of parts and materiel needed to make their IEDs, leaning “heavily on lawful commerce.” The CAR inquiry found much of what IS needs came from Iraqi and Turkish companies.

CAR researchers noted, “Both Iraq and Turkey have large agricultural and mining sectors, in which many chemicals and explosive components are employed extensively. At the same time, many small-scale commercial enterprises appear to have sold, whether wittingly or unwittingly, components to parties linked to, or employed by, IS forces.”

Most IEDs being encountered by the peshmerga use ammonium nitrate, found in fertilizer, mixed with other chemicals commonly used in farming, quarrying and mining.

They also are using the plastic explosive C4. The IEDs can be triggered by pressure pads, detonated by remote control or by trip wires, says Gen. Kakaye.