Bernie Sanders, who won 23 state contests in his fading quest to become the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee, was buoyed for months by supporters’ small average donations of $27. Conversely, Republican contender Jeb Bush flamed out in February despite his well-heeled connections.

Both experiences point to the limits of big money in U.S. politics, at least in the 2016 election cycle. But some political experts and most average Americans nonetheless see growing financial influence – which can vary with the primary or general election, increase further down the ballot and shape policies affecting daily life.

Americans of all stripes agree that money holds greater sway than ever, and the effects are mostly negative, a Pew Research Center survey found. The center reported in December that "large majorities favor limits on campaign spending and say the high cost of campaigning discourages many good candidates from running for president."

"There’s no country with longer and more expensive elections than the United States," said Ken Goldstein, a University of San Francisco professor and political advertising expert.

Campaigning for the presidency begins well over a year out; Republican Ted Cruz was the first to announce his candidacy in March 2015.

Spending in 2012 — the election cycle that included the last presidential race — topped $6.3 billion, the watchdog Center for Responsive Politics calculated.

This election cycle is expected to set records in spending by campaigns, political parties and outside interest groups, the center has forecast.

As of late May, candidates and the super PACS (political action committees) backing them raised more than $1.2 billion, according to campaign filings. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's campaign alone generated nearly $85 million, and supporting super PACs raised more than $204 million.

Real estate magnate Donald Trump largely has self-financed his campaign, but last month made a joint fundraising deal with the Republican National Committee enabling rich donors to contribute up to $500,000 apiece. He initially said he needed to raise $1 billion for the general election, but he has since scaled back.

His aides are expected to meet in coming days with those of billionaire industrialist Charles Koch, USA Today recently reported. The powerful Koch network of donors and policy developers may bypass the presidential contest — chafing at Trump’s stated opposition to free trade deals, for example — to focus on helping Republicans retain Senate control.

Concerns down the ballot

Norman Ornstein, a political scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, said he doesn’t “look at presidential politics as the be-all and end-all of the campaign funding system.”

Candidates for the nation’s top office already have “an enormous amount of name recognition” and extensive media coverage that lessen the impact of campaign spending on advertising.

More worrisome is what happens further down the chain — in congressional, legislative and local contests, he said.

Ornstein told VOA that “a whole bunch of senators” had privately divulged their fears about voting for legislation that could antagonize big donors.

“The part that troubles me most is judicial elections,” he added, noting heavy partisan spending aimed at tilting the composition of state Supreme Courts in Wisconsin and North Carolina. Ornstein speculated that a judge “may think twice” in deciding a case involving a giant corporation or wealthy individual whose support might be vital in future elections.

Landmark court decisions

Supreme Court decisions on Citizens United in 2010 and McCutcheon in 2014 relaxed campaign finance restrictions implemented in 2002.

The decisions have opened up "the wild West period of political spending," complained Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, a nonprofit advocacy group that seeks greater curbs on special-interest lobbying.

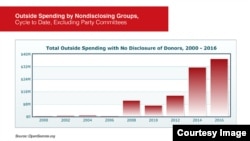

Weissman’s group is especially concerned about so-called dark money spent by politically active nonprofit groups that don’t have to disclose all their donors. The Center for Responsive Politics’ Open Secrets project notes that such spending surged "from less than $5.2 million in 2006 to more than $300 million in the 2012 presidential cycle."

"By and large, the dominant corruption in the United States is not bribery. It’s the shaping and influence of policy, and it’s done by and on behalf of the super-rich and the corporate class," Weissman said. "Those are the ones who make the political contributions and the ones to whom they [politicians] feel obligated. … Since the U.S. is the most powerful country, the corruption of our politics — the distortion of our politics — really affects everybody around the globe."

Candice Nelson, an American University government professor who heads the Campaign Management Institute, noted that, "compared to a lot of countries, the U.S. system is fairly transparent."

She, too, shared concern about dark money. "If any reform would be necessary, that would be it," Nelson said. "That said, I don’t really see that happening."

Opposed to restrictions

Cleta Mitchell, a partner and campaign finance expert in the Washington law office of Foley & Lardner, represents conservative causes and clients. She argues against any restrictions on campaign fundraising.

“You have to have money to get your message out. That’s just the truth,” Mitchell said. Referring to a new report on campaign news coverage, from the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, she noted that Trump "had more than $2 billion in free advertising. There was no way anybody, even poor Jeb Bush, could compete," she added.

“I think candidates need to be able to raise unlimited amounts of money,” Mitchell said, “so they can compete with whatever the media corporations decide they’re going to spend.”