DUBLIN —

What surprises Irish author Colm Toibin about his latest book is that it hasn't been burned.

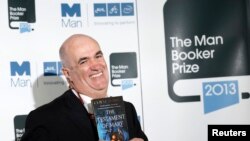

But he hopes the lack of controversy will not hold back his dark retelling of the Gospels, “The Testament of Mary,” from winning the Man Booker Prize on Tuesday at his third attempt.

In the novel, an aging, broken Mary bitterly recounts how “malcontents and half-crazed soothsayers” surrounded her son, helped lead him to a cruel death and then twisted his story to build a new faith.

In a country where just a few decades ago the Catholic Church could end the careers of writers it disapproved of, there has not been so much as an email to complain about a work that describes the gospels as “poisonous berries.”

“It is really interesting that you can write a book like this here and publish it and not a word,” said Toibin, 58, in an interview en route to the prize ceremony in London from Los Angeles.

“It hasn't been controversial. It isn't as though it's been burned anywhere.”

Toibin's is one of six novels in the running for the annual Booker, a coveted award that comes with a cheque for 50,000 pounds ($80,000), and, more importantly, a sizeable spike in international books sales.

The prize is open for the first time to authors from any country from 2014 as opposed to the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Commonwealth. Favorite in 2013 is Toibin's friend and English writer Jim Crace for “Harvest”.

Also shortlisted were Canadian Ruth Ozeki for “A Tale for the Time Being”, Indian/American Jhumpa Lahiri for “The Lowland”, New Zealander Eleanor Catton with “The Luminaries” and Zimbabwean NoViolet Bulawayo for “We Need New Names”.

“Lapsed Catholic"

Toibin, who explored European Catholicism in a 1994 travel book, describes himself as a “lapsed Irish Catholic," but has no time for mockery of the church that dominated his childhood.

“I waver between fierce doubt and a sort of awe at the grandeur of the business of building an entire world view, a religious faith on the death of one man and three years of his life,” he said.

The novel, he said, was not intended as an attack on the church or its teachings, but as an exploration of images and stories that were seared onto his psyche as an altar boy in Ireland in the 1960s.

Its darkness, he said, echoes his memories as a seven-year-old in a dimly-lit church, with vast images of a bloodied Christ and a priest warning “death comes soon and judgment will follow.”

As the novel opens, Mary's memories are being twisted by two unnamed Gospel writers who want a version of events worthy of the son of God.

She listens patiently as one explains to her how her son was conceived and how she helped take his body from the cross.

Instead she feels pangs of shame as she recalls fleeing the crucifixion when she realized her life was in danger and how she stood by as a family was robbed by her companions.

Mary voices doubt

The novel does not attempt to disprove the miracles, but lets Mary voice her doubts: that the wine in the jugs she saw was ever water and whether Lazarus had ever really died.

Toibin sees an echo of Mary's pain in the mother of suicide bombers or political hunger strikers chosen to die for a higher cause. “It's a much more pressing issue now than it has been for a long time,” he said.

While the novel has largely avoided controversy, a staging of the play on which it is based attracted around 100 protesters in New York this year, and a number of U.S. Catholics have sent him emails with abuse, “some of it true”, Toibin says.

Toibin seems more weary than excited about the idea of “putting a monkey suit in his bag” and attending another Booker Prize dinner next week after two previous novels “The Blackwater Lightship” and “The Master” both lost after being shortlisted.

But he is not paying any heed to the bookmakers, who have Crace as favorite.

“The judges could have something entirely surprising, in which case you just to bow your head and applaud the winner,” Toibin said. “I won't have a speech in my inner pocket,” he said. “I'm not doing that this time. I promise.”

But he hopes the lack of controversy will not hold back his dark retelling of the Gospels, “The Testament of Mary,” from winning the Man Booker Prize on Tuesday at his third attempt.

In the novel, an aging, broken Mary bitterly recounts how “malcontents and half-crazed soothsayers” surrounded her son, helped lead him to a cruel death and then twisted his story to build a new faith.

In a country where just a few decades ago the Catholic Church could end the careers of writers it disapproved of, there has not been so much as an email to complain about a work that describes the gospels as “poisonous berries.”

“It is really interesting that you can write a book like this here and publish it and not a word,” said Toibin, 58, in an interview en route to the prize ceremony in London from Los Angeles.

“It hasn't been controversial. It isn't as though it's been burned anywhere.”

Toibin's is one of six novels in the running for the annual Booker, a coveted award that comes with a cheque for 50,000 pounds ($80,000), and, more importantly, a sizeable spike in international books sales.

The prize is open for the first time to authors from any country from 2014 as opposed to the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Commonwealth. Favorite in 2013 is Toibin's friend and English writer Jim Crace for “Harvest”.

Also shortlisted were Canadian Ruth Ozeki for “A Tale for the Time Being”, Indian/American Jhumpa Lahiri for “The Lowland”, New Zealander Eleanor Catton with “The Luminaries” and Zimbabwean NoViolet Bulawayo for “We Need New Names”.

“Lapsed Catholic"

Toibin, who explored European Catholicism in a 1994 travel book, describes himself as a “lapsed Irish Catholic," but has no time for mockery of the church that dominated his childhood.

“I waver between fierce doubt and a sort of awe at the grandeur of the business of building an entire world view, a religious faith on the death of one man and three years of his life,” he said.

The novel, he said, was not intended as an attack on the church or its teachings, but as an exploration of images and stories that were seared onto his psyche as an altar boy in Ireland in the 1960s.

Its darkness, he said, echoes his memories as a seven-year-old in a dimly-lit church, with vast images of a bloodied Christ and a priest warning “death comes soon and judgment will follow.”

As the novel opens, Mary's memories are being twisted by two unnamed Gospel writers who want a version of events worthy of the son of God.

She listens patiently as one explains to her how her son was conceived and how she helped take his body from the cross.

Instead she feels pangs of shame as she recalls fleeing the crucifixion when she realized her life was in danger and how she stood by as a family was robbed by her companions.

Mary voices doubt

The novel does not attempt to disprove the miracles, but lets Mary voice her doubts: that the wine in the jugs she saw was ever water and whether Lazarus had ever really died.

Toibin sees an echo of Mary's pain in the mother of suicide bombers or political hunger strikers chosen to die for a higher cause. “It's a much more pressing issue now than it has been for a long time,” he said.

While the novel has largely avoided controversy, a staging of the play on which it is based attracted around 100 protesters in New York this year, and a number of U.S. Catholics have sent him emails with abuse, “some of it true”, Toibin says.

Toibin seems more weary than excited about the idea of “putting a monkey suit in his bag” and attending another Booker Prize dinner next week after two previous novels “The Blackwater Lightship” and “The Master” both lost after being shortlisted.

But he is not paying any heed to the bookmakers, who have Crace as favorite.

“The judges could have something entirely surprising, in which case you just to bow your head and applaud the winner,” Toibin said. “I won't have a speech in my inner pocket,” he said. “I'm not doing that this time. I promise.”