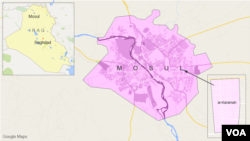

The prize is close. In a village just two kilometers from Mosul, the head of Iraq's Special Forces, General Talib Shaghati, held an impromptu news conference with several reporters to announce “good news” for more than a million civilians trapped in the Islamic State’s last major urban stronghold in Iraq.

With the thud of mortars landing in the background, plumes of black smoke billowing on the horizon, and a warplane roaring overhead as it struck an IS position, the general pledged, to "clear Mosul of terrorists very soon." He confirmed some of his forces have now entered Karama, a neighborhood just inside the city.

Shaghati urged Mosul’s mainly Sunni Muslim civilians to remain in their homes and to avoid going near IS buildings in the besieged city where, two years ago, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared his Sunni caliphate straddling Iraq and Syria.

Surrounded by black-clad soldiers, some wearing face masks and cradling AK-47s in their arms, the general spoke about how well coalition forces are coalescing in the fight against IS.

Ominously, though, some of his men had hoisted a Shi’ite flag on a military truck right by him, and in the nearby wrecked Christian town of Bartilla, recaptured from the jihadists 11 days ago after a fierce days-long battle, several Shi’ite banners fluttered Monday above ruined buildings.

An hour before Gen. Shaghati spoke to VOA and other reporters, coalition cooperation seemed in short supply at a checkpoint four kilometers from Bartilla on the main Mosul-Irbil road, where a brawl broke out between Kurdish peshmerga fighters and mainly Arab Iraqi commandos.

Tempers flare

The allies threatened to shoot each other as they drew their weapons amid angry shouts and an exchange of abuse.

No shots were fired, cooler heads prevailed, but the flare-up scattered dozens of Christians who had been waiting impatiently for hours to be allowed to visit their homes in Bartilla and who had been blocked at the berm-protected checkpoint by the Iraqi military from doing so — to their distress and rising anger.

The peshmerga were frustrated, too, at the rough commands of their Iraqi counterparts. Shi’ite music blaring from a couple of Iraqi Humvees that were waved through the checkpoint aggravated tensions between Kurds, Christians and the mainly Shi’ite fighters of the Iraqi Special Forces.

"The Iraqi military is blocking our people from getting inside Bartilla," Romio Hakari, head of the Christian Bet-Nahrain Democratic Party, told VOA.

"They say it is because of security problems and of danger but that is only partly true," he added, acknowledging there remains the menace of booby-trap bombs and unexploded ordnance, as well as fierce fighting in the nearby villages of Bazwaya and Gogjali right on the threshold of Mosul. But he added, "There is an underlying mistrust and Christians fear what will happen to them and worry about the future of our ancestral towns."

Christian towns

Those fears have mounted with the flying of Shi’ite banners in towns like Bartilla, which Hakari deems "provocative." "Only the regular Iraqi army was meant to be here but it seems like there are many other forces," he said, including fighters, he claims, from the irregular Shi’ite militia Hashd al-Shaabi.

Under an agreement brokered partly by U.S. officials, Hashd al-Shaabi militiamen are meant to be fighting only on the western and southwestern outskirts of Mosul, and only regular Iraqi army troops and peshmerga are meant to be present on the eastern front here at Bartilla. The peshmerga, under the agreement, are standing aside to let Iraqi forces take the battle into the mainly Sunni Muslim city.

VOA could not confirm that Hashd al-Shaabi militiamen are present in the Christian towns of the Nineveh plains, but locals believe they are — adding to their fears about whether they will ever be able to return to their homes or, if they are, whether they will feel safe.

Christians had fled days and in some cases hours before IS fighters arrived in their towns and villages in August 2014. IS threatened to slaughter them. Most fled to the Kurdish capital of Irbil, settling in the Christian district of the city, Ankawa, in what ever accommodation they could find.

Some Christians say they will return to live in the region — especially if their towns and villages are incorporated into Kurdistan, but others are gloomier, arguing the days of Christianity here are over because the social fabric has been torn irreparably by IS.

In conversation with nearly a dozen Christians at the checkpoint waiting to be allowed to visit Bartilla to salvage what they can, no interviewee expressed much confidence.

"There are two problems," said Nimrud, a 54-year-old father of nine. "I would like to go back but I will only do so if we are protected, and if funds are supplied to help us rebuild — otherwise it will be too difficult," he added.

History, community

Rami, a 27-year-old who left Mosul 10 years ago because of tensions with Sunni Muslims in the city, said he has had enough. "I have seen my house on TV and it has been destroyed. I don’t think we will go back to live in the Nineveh plains; I don’t think Christians have a future in Iraq," he said.

Iraqi lawmaker Jamila al-Ubaidy, a Sunni Muslim, also expressed frustration at the checkpoint, where she, too, waited to visit her family’s village on the outskirts of Mosul, saying, "People are worried and want to see what is left of their homes and to make sure more of their property isn’t destroyed in the meantime." She isn't explicit, but she suggests local Christians and Sunnis are scared Shi’ite soldiers will loot what’s left in their properties.

Former US ambassador Alberto Fernandez, who has followed closely the travails of Christianity in the region, is pessimistic.

"For Christians to feel safe there needs to be: security, autonomy [or local rule], and some sort of economic basis for living," he argued. "Traditionally the people of the Nineveh plains had close ties with Mosul and worked or traded with the city, so the whole fabric of life has been ripped apart. It is not impossible to recreate this social fabric, but it requires a care and commitment no one – international community, Baghdad – seem to have,” he lamented.

He added, "What is lost if these communities cease to exist in Iraq is not only a historic presence but a chance of creating a community of real diversity and tolerance. Iraq would just be a grimmer, more intellectually and spiritually impoverished place."