Iran, with a little help from China, is putting together its own closed version of the Internet to keep its citizens from viewing material it considers unsuitable. Experts say the project is struggling and unlikely to work.

The project, begun a few years ago, is driven by concerns over national security as well as censorship, according to Mahmoud Enayat, director of Small Media, a London-based organization that works to increase the flow of information in closed societies.

Enayat says the Iranian government concluded that it was facing security threats whenever its government and banking information moved on the Internet through computer servers outside the country.

“So what they started doing was to build infrastructure inside Iran. So that allows them to keep the traffic internally; and also they can manage it,” Enayat said.

Around 90 percent of the government’s websites have already been moved onto Iranian-based servers, according to Freedom House research analyst Adrian Shahbaz.

“There is no doubt the Iranian government has been looking to other repressive countries, such as China, as a model and even vendor for the sort of sophisticated hardware and software controls that it needs to maintain strict control over how Iranians use the Internet,” said Shahbaz.

And Eva Galperin, an analyst with the Electronic Frontier Foundation in California, says Iran appears to be copying the Chinese model of creating native tools and social networks similar to Weibo, China’s Twitter counterpart. “But it turns out that building these services is very hard.”

Iran, a nation under international economic and political sanctions, faces special difficulties in buying the equipment and expertise to deploy sophisticated systems that can provide the security and control it is seeking for online communications. As a workaround, Shahbaz said Iranians are trying to build many of their own surveillance systems from scratch and pirating software demonstration versions to tailor them to their needs.

Chinese Suppliers

Some equipment is still being acquired clandestinely, said Enayat. But more often, he said the hardware comes from Chinese companies or proxy companies in Malaysia or Thailand.

“No Western companies sell this equipment to Iran because … there’s been enough pressure by the Western governments on Western companies that sell these things,” Enayat said. “The Chinese is where the problem is still there. And actually the Chinese government doesn’t care. The companies themselves, because of fear of losing business in the U.S., have slowed it down, but they haven’t shut it down completely.”

But Galperin notes that while there is evidence that Iran is using Chinese networking hardware in its project, the extent of Chinese help is still unclear.

One example of Chinese assistance came to light last year, according to Shahbaz, when it was learned that China’s ZTE company had signed a contract with Iran to provide more than $130 million in surveillance and interception equipment. He said a there was also a 2010 deal for China to sell Iran “deep packet inspection” technologies that could monitor Internet communications.

All of this, Shahbaz said, is designed to enable Iran to set up its internal Internet services and crack down on access to regular Internet services.

The internal network is also designed to prevent Iranians from surfing the Internet, even the internal one, anonymously.

Clampdown on Anonymous surfing

“All Internet Protocol [IP] addresses are going to need to be registered, and that’s going to make it easy to identify who is looking at what websites at any given time,” Shahbaz said.

And Enayat notes that Tehran is looking to block access to commercial tools and services that large numbers of Iranians have already used to bypass filtering of websites such as Facebook and YouTube.

That is exactly what happened ahead of the June presidential election, said Galperin, when authorities turned off some of the Internet’s encrypted communications to make secure browsing more difficult.

“The control comes and goes and they can’t really manage a … sustained control. And this is not merely some sort of technical problem, but a social problem,” said Galperin. “If you stand between people and certain types of secure communications for too long, you’re going to get social unrest.”

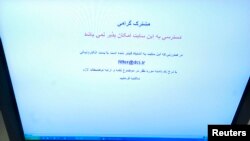

Iran’s National Information Network project would create two internets: one based on domestic servers, the other a very slow and filtered international Internet.

“It’s going to force a lot of Iranians, whether they like it or not, to be using this clean version of the internet,” Shahbaz said. “And that’s going to consist of only pre-approved sites and products that the Iranian authorities will offer.”

But he cautioned that it will be very difficult to accomplish this “in a country where even the supreme leader [Ali Khamenei] has his own Twitter account.”

Even the former Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, had a Facebook page. And newly-elected President Hassan Rouhani has come out recently in favor of Facebook and said attempts to filter Internet access were futile, despite the fact that Facebook is blocked in the country and Internet filtering continues, said Galperin.

‘Soft War’ with the West

But whatever its leaders do in their personal Internet use, Shahbaz says Iran’s national policy is based on the view that it is in a “soft war” with the West and that Tehran is “looking to close itself off and build its national Internet - because it really sees itself as under attack in this ‘soft war.’”

Jeffrey Carr, an analyst with Taia Global, a cyber security corporation in Washington State, says there is a good reason Iranian leaders feel this way.

“There was a period of time when at least a half-a-dozen major cyber espionage tools were found on Iran’s networks,” Carr said. “So I think that that actually is a huge motivation for them to try to find ways to isolate their network.”

But despite its efforts, Carr says Iran’s network project is a poorly-thought out solution. “Iran still has to be connected to the outside world,” he said, and “so as long as it has those connections in place, it’s going to have its population attempting to utilize those connections for Internet access.”

Carr predicts that Iran will either back away from its project or have to modify it extensively.

“They’ll probably wind up with something akin to China’s great firewall, but that’s going to be it. I really don’t expect them to succeed in completely isolating the population from the Internet. You simply cannot remove yourself from the global Internet.”

The project, begun a few years ago, is driven by concerns over national security as well as censorship, according to Mahmoud Enayat, director of Small Media, a London-based organization that works to increase the flow of information in closed societies.

Enayat says the Iranian government concluded that it was facing security threats whenever its government and banking information moved on the Internet through computer servers outside the country.

“So what they started doing was to build infrastructure inside Iran. So that allows them to keep the traffic internally; and also they can manage it,” Enayat said.

Around 90 percent of the government’s websites have already been moved onto Iranian-based servers, according to Freedom House research analyst Adrian Shahbaz.

“There is no doubt the Iranian government has been looking to other repressive countries, such as China, as a model and even vendor for the sort of sophisticated hardware and software controls that it needs to maintain strict control over how Iranians use the Internet,” said Shahbaz.

And Eva Galperin, an analyst with the Electronic Frontier Foundation in California, says Iran appears to be copying the Chinese model of creating native tools and social networks similar to Weibo, China’s Twitter counterpart. “But it turns out that building these services is very hard.”

Iran, a nation under international economic and political sanctions, faces special difficulties in buying the equipment and expertise to deploy sophisticated systems that can provide the security and control it is seeking for online communications. As a workaround, Shahbaz said Iranians are trying to build many of their own surveillance systems from scratch and pirating software demonstration versions to tailor them to their needs.

Chinese Suppliers

Some equipment is still being acquired clandestinely, said Enayat. But more often, he said the hardware comes from Chinese companies or proxy companies in Malaysia or Thailand.

“No Western companies sell this equipment to Iran because … there’s been enough pressure by the Western governments on Western companies that sell these things,” Enayat said. “The Chinese is where the problem is still there. And actually the Chinese government doesn’t care. The companies themselves, because of fear of losing business in the U.S., have slowed it down, but they haven’t shut it down completely.”

But Galperin notes that while there is evidence that Iran is using Chinese networking hardware in its project, the extent of Chinese help is still unclear.

One example of Chinese assistance came to light last year, according to Shahbaz, when it was learned that China’s ZTE company had signed a contract with Iran to provide more than $130 million in surveillance and interception equipment. He said a there was also a 2010 deal for China to sell Iran “deep packet inspection” technologies that could monitor Internet communications.

All of this, Shahbaz said, is designed to enable Iran to set up its internal Internet services and crack down on access to regular Internet services.

The internal network is also designed to prevent Iranians from surfing the Internet, even the internal one, anonymously.

Clampdown on Anonymous surfing

“All Internet Protocol [IP] addresses are going to need to be registered, and that’s going to make it easy to identify who is looking at what websites at any given time,” Shahbaz said.

And Enayat notes that Tehran is looking to block access to commercial tools and services that large numbers of Iranians have already used to bypass filtering of websites such as Facebook and YouTube.

That is exactly what happened ahead of the June presidential election, said Galperin, when authorities turned off some of the Internet’s encrypted communications to make secure browsing more difficult.

“The control comes and goes and they can’t really manage a … sustained control. And this is not merely some sort of technical problem, but a social problem,” said Galperin. “If you stand between people and certain types of secure communications for too long, you’re going to get social unrest.”

Iran’s National Information Network project would create two internets: one based on domestic servers, the other a very slow and filtered international Internet.

“It’s going to force a lot of Iranians, whether they like it or not, to be using this clean version of the internet,” Shahbaz said. “And that’s going to consist of only pre-approved sites and products that the Iranian authorities will offer.”

But he cautioned that it will be very difficult to accomplish this “in a country where even the supreme leader [Ali Khamenei] has his own Twitter account.”

Even the former Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, had a Facebook page. And newly-elected President Hassan Rouhani has come out recently in favor of Facebook and said attempts to filter Internet access were futile, despite the fact that Facebook is blocked in the country and Internet filtering continues, said Galperin.

‘Soft War’ with the West

But whatever its leaders do in their personal Internet use, Shahbaz says Iran’s national policy is based on the view that it is in a “soft war” with the West and that Tehran is “looking to close itself off and build its national Internet - because it really sees itself as under attack in this ‘soft war.’”

Jeffrey Carr, an analyst with Taia Global, a cyber security corporation in Washington State, says there is a good reason Iranian leaders feel this way.

“There was a period of time when at least a half-a-dozen major cyber espionage tools were found on Iran’s networks,” Carr said. “So I think that that actually is a huge motivation for them to try to find ways to isolate their network.”

But despite its efforts, Carr says Iran’s network project is a poorly-thought out solution. “Iran still has to be connected to the outside world,” he said, and “so as long as it has those connections in place, it’s going to have its population attempting to utilize those connections for Internet access.”

Carr predicts that Iran will either back away from its project or have to modify it extensively.

“They’ll probably wind up with something akin to China’s great firewall, but that’s going to be it. I really don’t expect them to succeed in completely isolating the population from the Internet. You simply cannot remove yourself from the global Internet.”