They called the makeshift machines used to print underground pamphlets and papers "Vietnamitas" in homage to the war waged by the Viet Cong in Vietnam.

It was symbolic of the odds faced by Spanish communists, socialists, students and dissident priests who saw themselves as a kind of guerrilla force fighting the might of the dictatorship of General Francisco Franco.

Despite the ruthlessness of the regime, they believed that by spreading the word, they hoped to bring down El Caudillo — The Leader — as Franco was known.

Faced with stringent censorship, many paid with their lives for challenging the dictatorship.

Pedro Patino, a Communist Party activist and union official, was shot dead by the Spanish civil guard in 1971 as he tried to distribute a pamphlet called El Socialista.

Patino used his daily wages and a large part of his time to produce the paper. He is among the cases recorded in a new book about Spain's own samizdat —clandestine movement — that fought Franco.

Jesus A. Martinez, a professor of contemporary history at Complutense University of Madrid, spent six years investigating what he calls the “ink battle” against the dictatorship.

He uncovered 5,000 documents from public and private archives that attest to the efforts undertaken to present an alternative to the narrative propagated by Franco and his right-wing National Catholicism government.

His book Vietnamitas Contra Franco (Vietnamitas Against Franco) details those findings.

A law enacted during the Spanish Civil War said that "nothing could be published without the permission of the regime,” Martinez told VOA. That conflict lasted from 1936 to 1939.

“But these people were never censored. They always lived in a world away from that, a dissident world,” said Martinez, who expressed surprise at the sheer size of the underground world.

Martínez said the Franco government imprisoned and fined those caught producing underground publications or anything else that challenged the narrative of the regime.

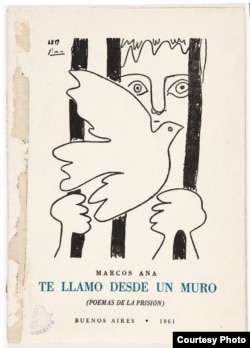

The fight against Franco extended beyond newspapers to women’s magazines, poetry, drawings and posters.

The book details the ingenuity of the underground campaigners, who believed that one day they could topple the dictatorship with words. They used suitcases with false bottoms and hid speeches by left-wing leaders in the covers of recipe books, which were smuggled from France into Spain to inspire the communists and socialists living there.

During the 1960s, the regime turned its attention from communists to rebellious students, as the rest of the world underwent a social revolution from which Spain was isolated.

Researchers have uncovered how, in two months in 1969, police raided the homes of 415 students and 390 workers, leading to 383 arrests.

From 1964 to 1973, the Public Order Court prosecuted 53,500 people. Of the 11,261 cases, 2,622 were for illegal propaganda and 3,658 for illicit association — a charge that could be brought in connection with producing underground media.

Ultimately for many, the hope of toppling Franco came to nothing. The dictatorship lasted from 1939 until 1975, when the general died in his bed.

Soledad Fox Maura, a professor of Spanish and comparative literature at Williams College in Massachusetts, told VOA that underground opponents of military rule played a vital role in bringing democracy to Spain.

Fox Maura is the author of Exile, Writer, Soldier, Spy, a book about the life of Jorge Semprun, an author, French resistance fighter and Nazi concentration camp survivor who worked undercover for the communists during the dictatorship and later became a government minister.

She recounted the story of Domingo Malagon Alea, a so-called master forger who produced fake passports for communists.

“This man was an artist before the war, and he was a genius at forging these passports,” Fox Maura told VOA.

“The clandestine anti-Franco militants had an important role in bringing democracy to Spain. It took nearly four decades, but they had laid much of the groundwork before Franco’s death.”

Samizdat comes from the Soviet era when underground media in Russia and other Eastern Bloc communist states sought an alternative narrative to that of the totalitarian communist states.

In modern-day Russia, this tradition has been revived by activists who seek to combat media crackdowns by President Vladimir Putin.

As Russia tries to control information on the war in Ukraine, online news producers and aggregators face the threat of fines.

Apps and even people who share information online have been hit with penalties.

In July 2022, a Russian court fined Google more than $370 million for refusing to remove information about the war from its platforms, including YouTube.

In March 2023, a Siberian court sentenced a freelance journalist to eight months’ corrective labor for “knowingly distributing” in social media posts “false information” about the Russian army.

Andrei Novashov, who worked for media outlets including RFE/RL’s Siberia Realities project, is also barred from posting online for a year.

Modern-day Spain has one of the better records for defending the press. Media watchdog Reporters Without Borders describes the country as “tolerant” of diversity and notes few journalists are pressured by authorities.

Alfonso Bauluz, president of media watchdog Reporters Without Borders, says there is no comparison to the Franco era censorship of the media, but challenges remain.

"There are some changes, maybe more violence in the street towards journalists because of greater political polarization,” he said.