Cyber espionage has cost U.S.-owned businesses about $14 billion in reported economic losses since last October, according to the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). But private security experts said this is a fraction of a huge problem that will take a cultural shift to put corporate America ahead of today’s high-tech spies.

Martin Libicki, a Washington-based senior management scientist with RAND, a non-profit research and analysis institution, said nobody knows how big the problem is. “It takes a lot more worth than we’ve been willing to give it to try to estimate the size of the problem.”

“I don’t have an even good theoretical estimate, much less a practical estimate,” he added.

Companies are often too embarrassed to announce a security breach because people don’t always notice it when it first happens. “It takes an average of a year and a half before you realize that something is wrong,” said Libicki.

- "In the US ... most companies are careful about their source code, but they send people into the field with sales leads and customer lists stored on mobile devices or unencrypted laptops."

- Damien Miller, CEO of Comet Way

Canada’s telecommunications company, Nortel, for example, told the Wall Street Journal in February that it lost data for nearly a decade before realizing it was being spied on.

Randall Coleman, FBI Section Chief at the agency’s Counterintelligence department in Washington said hacking by both organized groups and state-backed actors has taken off in recent years. “It is certainly the wave of the future,” he said.

“There are state-sponsored corporations throughout the world that spy on the United States and attempt to steal our technology,” Coleman added.

One of the most frequently accused is China. But the Chinese government has repeatedly denied involvement in cyber espionage, saying it also suffers from the problem.

But Jody Westby, CEO of Global Cyber Risk, a consulting company said it is hard to know if the perpetrator is “the kid down the street, a teenager seeking gratification, a terrorist, a hacker, a nation-state, an insider - you don’t know.” She said it all starts from the premise that this was an unauthorized illegal activity.

The biggest threat is not coming from nations, but from other corporations, said cyber security expert Damien Miller, CEO of Comet Way, a cyber security company.

A case in point is the legal action American Superconductor Corporation (AMSC), a global energy solutions provider, has brought against China’s Sinovel Wind Group Company. While AMSC has declined interview requests, its website stated that the company is seeking more than $1.2 billion in damages stemming from “contractual breaches and property theft.”

Roel Schouwenberg, Senior Researcher with IT security company Kaspersky said cyber criminals typically go after companies with the weakest defenses. But with the kinds of targeted attacks taking place today, he said “everybody needs to have very strong security. It’s no longer about being better than the weakest one.”

The Stuxnet and Duqu era

A few years ago, industrial spies mostly targeted Fortune 100 companies, but now all sorts of companies all over the world are being affected. “That’s definitely worrisome,” said Schouwenberg, because “for the longest time we’ve been working under the impression that as long as you are more secure than your competitors, you are fine.”

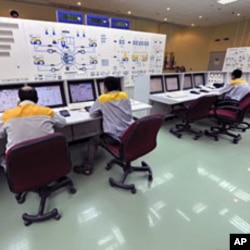

But the increasing sophistication of recent malicious software or malware has raised the threat level. Schouwenberg specifically cited Duqu, an intelligence tool that looks for data that could be useful for attacking industrial control systems, and its 2010 predecessor, Stuxnet, a ground-breaking cyber-weapon designed to sabotage machinery in an Iranian nuclear enrichment facility.

While security experts believe Duqu and Stuxnet were probably created by the same developers, Schouwenberg said this top-tier malware is now functioning “as a source of inspiration for regular cyber criminals.”

Today’s threats sneak in and lie undetected for months before making a move, said Westby. They can circumvent anti-virus software - even change it to remain undetected - and load other software on the computer. “You can get a malware kernel in there that’s then starting to bring in keystroke loggers [and] Trojans, these kinds of other malware that they can use to then steal data.”

She added that “companies are just not prepared to deal with this level of sophistication.”

She said businesses have a “false sense of security” that firewalls and anti-virus programs provide enough protection. “They need to re-evaluate how they are approaching threats. And it’s not just going to be a technological solution,” she said.

How to protect corporate data

Some of the immediate steps companies can take, Westby said, include re-evaluating whether or not they have the right personnel and adequate budgets, and whether roles and responsibilities are aligned so that their various entities communicate effectively when anomalies occur.

“All you can do is defend well and have good mitigation and practices in place,” said Schouwenberg. “So, that means different layers of security, and so on, where you try to stop these guys from ever getting in. Or, be very aware if somebody does manage to get in that you catch them very, very quickly and minimize the damage,” he said.

“The first question you have to ask yourself,” said Libicki, “is when it comes to things like protecting your network is what do you have that’s worth protecting?”

Companies also could be overestimating the need to share information via live connections, he said. And Miller agreed, saying U.S. businesses are not good at identifying at-risk assets. They guard their source code, he said, but then send into the field sales leads and customer lists stored on mobile devices or unencrypted laptops that hackers can easily break into.

Even in critical U.S. infrastructure, Schouwenberg said some networks that should not be connected to the Internet, in fact, are. “And this is because people are not following proper procedure,” he said. “So, access controls - that’s really what it boils down to - are definitely something which is very important.”

“There has to be due diligence in what is out there, in what a company decides to put out there,” said Coleman. “And then a company really has to make sure that there’s auditing and monitoring capabilities to ensure that their information is protected.”

As a Carnegie-Mellon Cylab fellow, Westby conducts annual surveys on how boards and senior executives govern and practice security. She said surveys she has done since 2008 show “very little change” in how boards and senior executives look at these threats.

Wanted: new thinking, fewer mandates

But a cultural shift is slowly taking place, said Miller, with some companies issuing “blank” laptops and mobile phones to employees traveling to high-risk areas. He said other businesses are starting to adopt federal standards of authentication and data security.

Schouwenberg said what is needed is legislation that incentivizes better security, similar to Massachusetts‘ aggressive Data Privacy Law, which fines companies that fail to follow best practices.

A proposed cyber espionage bill being debated by the U.S. senate lets the U.S. Department of Homeland Security set cyber security standards for private companies.

But Westby questioned whether Congress is on the right track with this legislation, saying cyber security will never get better unless cyber crime is addressed. “Right now, we can’t catch the bad guys,” she said.

“When you have laws around the world that don’t even consider certain acts of cyber crime, when they don’t have anyone that’s skilled to help with an investigation, when there aren’t even 24/7 points of contact to call, then it’s difficult,” Westby said. “And it’s difficult not just in developing countries. It’s difficult here.”

Westby said this requires the United States to exert more leadership globally to enhance cooperation and ensure that countries have harmonized laws and trained law enforcement personnel.

“The threats are going to remain there,” she said, adding that requiring companies to comply with more federal mandates is not the answer because it takes resources away from “deploying the best mousetrap or taking the best approach to security.”

And in this high-tech cat-and-mouse game, U.S. companies cannot allow technology to leave them behind, cautioned the FBI's Coleman.