As Indonesians head to the polls Wednesday to decide a tight presidential race, there’s concern that corruption and a complicated electoral process will discourage eligible young people from casting votes.

The third presidential election in the Southeast Asian island nation’s history pits Joko Widodo, the governor of Jakarta, against Prabowo Subianto, a former military general.

Almost 55 million of Indonesia’s nearly 190 million registered voters fall in the 17- to 29-year-old age range, according to the Central Statistics Agency. At nearly 30 percent of the electorate, they could play a key role in the presidential race, now considered too close to call.

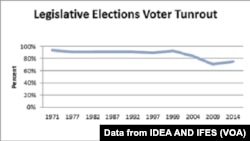

“There is a concern that turnout could be less than in previous elections, and this is of particular concern when it comes to young voters,” said Vikram Nehru, chair of Southeast Asia studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington-based think tank. Nehru estimated there are 22 million eligible voters ages 17 to 21.

One nongovernmental organization looking to improve civic participation among young voters is Ayo Vote or Let’s Vote, conceived during the 2012 Jakarta gubernatorial elections.

Ayo Vote aims to engage youth by educating them and demystifying Indonesia’s election process.

“There is no media in Indonesia that covers the election specifically for the young voters, and it’s a different type of information that they need,” said Pingkan Irwin, the organization’s co-founder. “We wanted to make the process as simple as possible and information easy to digest for them so they get interested in talking about the election.”

Indonesia’s election process is so complicated that, in recent national and local parliamentary races, almost 235,000 candidates vied for more than 19,000 seats.

Voter-eligibility rules are confusing, too. For example, while the minimum voting age is 17, anyone who is married and has an identity card can vote. Females as young as 16 can marry legally.

In the April 9 legislative elections, many young people did not even know the district in which they could vote, Irwin said. “How can they choose their candidates wisely if they don’t even have the basic information for that?”

Ayo Vote provides such information on its website and social media accounts.

During recent presidential debates, Ayo Vote held viewing parties so young voters could discuss the candidates and their platforms. Some events – sponsored by the local election commission and NGOs – attracted hundreds of participants, Irwin said.

“It’s better to watch it together and flip through the information together, because sometimes it gets pretty technical and sometimes you get lost in the debate,” Irwin said.

Hurdles to youth participation

Irwin said it’s challenging to engage some young, prospective voters, who might feel powerless or be easily misled by campaigns.

Nehru said scandals involving various Indonesian political parties also have fostered “a certain amount of apathy toward politics.”

Last week, the former chief justice of Indonesia’s constitutional courts was given a life sentence for corruption and money laundering.

Young people may be less inclined to vote because they take democracy for granted, Nehru said. They experienced little, if any, of Suharto’s repressive authoritarian rule from 1965 to 1998.

“They were very young during the time of Suharto’s departure, and all they’ve really known is a free and independent and democratic Indonesia,” Nehru said.

Tuning out social media ‘noise’

Each presidential candidate’s camp has used social media extensively, often to attack his rival. Widodo, identified as a Christian of Chinese descent, has called Subianto a “psychopath” who had failed a mental health test while in the military, The New York Times reported.

Young Indonesians are increasingly savvy about social media, said Michelle Chang, who manages technology programs for the Asia Foundation, a nonprofit development organization. Jakarta has been called the world’s No. 1 Twitter city based on the number of tweets.

But Irwin suspects the extensive use of social media – by candidates and young people – may be distracting attention from substantive issues.

“They’re talking so much on social media, and it’s very noisy,” she said. “Sometimes a lot of the discussion is making fun of people.”

Instead, her organization wants to “drive the conversation about the real issues.”

One is employment.

“A big concern amongst young voters is: Will I be able to get a job, will this economic growth allow me an improvement in my own standard of living?” said Nehru, of the Carnegie Endowment.

While Indonesia’s economy has grown rapidly over the past decade, there hasn’t been a commensurate increase in jobs, Nehru said. “This has been largely ‘jobless growth’ and in fact amongst the unskilled population, real wages have either stagnated or even declined. And as a result, inequality has increased.”

Indonesia, along with Russia, saw the highest levels of income inequality from 2006 to 2011, according to Euromonitor International, a London-based market research company.

Nehru said the political parties as well as organizations like Ayo Vote must engage young people.

“Young voters need to be energized, they need to feel themselves as important in shaping Indonesia’s future by voting for a candidate and therefore take greater interest… and deciding who they would want to vote for based on how their candidates stand on these issues.”