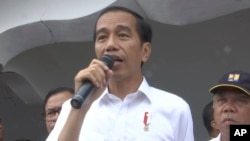

Four years after coming into office, Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s goal of food sovereignty continues to be a work in progress.

In his vision, Indonesia would be able to produce main commodities such as rice, corn and soy. But the government’s recent decision to import 100,000 tons of corn for cattle feed until the end of the year indicates the goal is far from fruition.

The Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture said the decision was made because the price of corn has increased in several areas because of the cost of logistics, not because of a decrease in production.

Agung Hendriadi, the head of Food Security Agency at the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture, said that Indonesia produces enough corn to meet the local demand.

“In fact, our production has a surplus,” he said. As of 2018, Indonesia produces 28.48 million tons.

Food sovereignty vs. security

According to Dwi Andreas Santosa, a professor of agriculture at the Bogor Agricultural Institute, the concept of food sovereignty includes protection of farmers against what he called an unfair international trading system.

“Based on our experiences, too much imports on different commodities is almost always to the detriment of farmers,” he told VOA. Santosa added that the food sovereignty Jokowi is aiming for is different from food security, in which it does not matter where the food comes from as long as it can meet the demand.

Data from the Indonesian National Statistics Agency (BPS) shows Indonesia has managed to increase its agricultural exports by 24 percent to 31 million tons from 2016 to 2017. But Santosa argued the country’s dependency on imported commodities has also increased.

“Import data for seven main commodities rose from 21.7 million tons in 2014 to 25.5 million tons in 2017. This includes rice, soy, sugar, corn, wheat, garlic and tapioca. Last year, Indonesia became the biggest wheat importer. Import data in 2017 shows 12.5 million tons,” he said.

Wheat imports

Indonesia cannot produce wheat. And because the government reduced imports of corn by 60 percent, wheat imports for cattle feed surged from 200,000 tons in 2015 to 3 million tons in 2016. As for soy, Indonesia can only produce 30 percent of the local demand, more than 400,000 tons have to be flown in from overseas in 2018.

Hendriadi explained that his ministry has a program to localize raw materials used in the food industry to reduce imports.

“We will substitute imported commodities. To make flour, we have cassava, corn and banana,” he told VOA.

Widiyanto, program manager of Right to Food at Oxfam, said the biggest homework in Jokowi’s government to achieve food sovereignty is to establish a food authority agency. In Indonesia, production is handled by the Agriculture Ministry, and price stabilization by the Trade Ministry, while stock is kept by Logistics Affairs Agency.

“It’s not easy to harmonize three institutions that are directly related. The government should be serious to discuss the establishment of [a] food agency so there won’t be conflict among those institutions,” he said.

Widiyanto also mentioned Indonesia has lost more than 600,000 hectares of agricultural land within the last five years. That leaves the country with 7.1 million hectares of active land. But the majority of the farmers own less than 2 hectares of land.

Nevertheless, he lauded the president’s commitment to solve inequality and land conflict by issuing the presidential decree on agricultural reform Oct. 10. The decree will deal with land certification for farmers, which would allow them to access financial aid, land redistribution and giving the rights for local people to manage their forest with the social forestry scheme.

Data authority

The government has also admitted that data disparity is one of the main issues facing Indonesian agriculture. Starting this year, rice production data will only refer to statistics from the National Statistics Agency (BPS). Santosa said the BPS does not have conflict of interest in issuing data, whereas other related agencies might manipulate it.

“Only the current government dared to correct the data, and the BPS finally issued it. Data on rice this year, next year BPS will have corn and others,” he said.

But ultimately, according to Santoso, the concept of food sovereignty should have a goal to increase the welfare of farmers as the main actors in food production. The BPS noted that the farmer exchange rate slightly decreased in 2017 to 101.28 from 101.65 in 2016. This year, Hendriadi noted that the rate has increased to 102.25.

Fewer farmers

Santoso explained the farmer exchange rate is one of the indicators used to determine welfare. The rate is counted by subtracting the selling price of the farmer’s products with the price of products that they consume.

“If it goes under 100, that means he is at loss,” he added.

At the moment the agricultural sector is becoming less lucrative and many farmers have left their occupation, while the current government focuses on the amount of production and export.

“Indonesia lost 5 million farmers who stopped farming activities in the last 10 years. And now there are around 26 million farmers. Around 70 percent of active farmers are now above 45 years old,” Widiyanto said.

But Hendriadi said the data has shown an improvement in the country’s agricultural sector.

“Jokowi’s program (for food sovereignty) is running well, we are already self-sufficient in rice,” he added.