NEW DELHI, INDIA —

Health specialists in India are using fingerprint technology to make sure tuberculosis sufferers receive proper treatment for the deadly lung infection.

New Delhi resident Vishnu Maya has already noticed a difference in her health after a few weeks of treatment for the disease.

“I feel better. I have been feeling better for the last two to three days," she says. "I am not in a lot of pain right now.”

Maya goes to a neighborhood health center to take her TB medication in the presence of Neema Mehta, a counselor with the Indian NGO Operation Asha.

Mehta has the difficult job of ensuring that patients do not stop their treatment for any reason.

“We have to explain to them, because they see it is a six-month dose and they get worried that they have to take it for so long," she says. "We have to explain to them that there is no need to worry - that if you take your medication on time, you will get better.”

Tuberculosis remains a major health crisis for India, with two million people diagnosed each year.

Making sure patients complete treatment is crucial. Stopping can cause the lung infection to morph into a deadlier version called multiple drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), which is much more difficult and costly to treat.

India is estimated to be home to 100,000 such cases. But Operation Asha founder Dr. Shelly Batra fears the number is much higher, with thousands of people who remain undiagnosed.

“MDR-TB is the next plague that has the potential to wipe out millions," Batra says. "And if we don’t accept it now and we don’t act now by preventing drug resistance, we are going to be in very big trouble.”

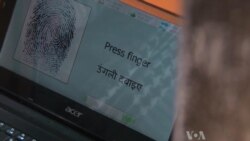

Batra is using biometric technology to ensure TB patients are completing their drug regimen.

Her organization has centers in nearly every corner of the city, where the fingerprints of patients and counselors are recorded as proof of interaction. Those who do not show up to take their medication are sent reminders and tracked down.

The monitoring system has already made a difference and cut the default rate in half, according to Batra.

“We have brought it down to three percent, and with our biometric technology we have brought it down to below 1.5 percent, which I believe is a huge savings," Batra says. "MDR-TB is not just human misery, it is a huge economic loss to the patient, to the country.”

With treatment centers in 3,000 Indian and Cambodian slums and villages, Operation Asha hopes its grass-roots effort, aided by technology, will help stem the tide of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis.

New Delhi resident Vishnu Maya has already noticed a difference in her health after a few weeks of treatment for the disease.

“I feel better. I have been feeling better for the last two to three days," she says. "I am not in a lot of pain right now.”

Maya goes to a neighborhood health center to take her TB medication in the presence of Neema Mehta, a counselor with the Indian NGO Operation Asha.

Mehta has the difficult job of ensuring that patients do not stop their treatment for any reason.

“We have to explain to them, because they see it is a six-month dose and they get worried that they have to take it for so long," she says. "We have to explain to them that there is no need to worry - that if you take your medication on time, you will get better.”

Tuberculosis remains a major health crisis for India, with two million people diagnosed each year.

Making sure patients complete treatment is crucial. Stopping can cause the lung infection to morph into a deadlier version called multiple drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), which is much more difficult and costly to treat.

India is estimated to be home to 100,000 such cases. But Operation Asha founder Dr. Shelly Batra fears the number is much higher, with thousands of people who remain undiagnosed.

“MDR-TB is the next plague that has the potential to wipe out millions," Batra says. "And if we don’t accept it now and we don’t act now by preventing drug resistance, we are going to be in very big trouble.”

Batra is using biometric technology to ensure TB patients are completing their drug regimen.

Her organization has centers in nearly every corner of the city, where the fingerprints of patients and counselors are recorded as proof of interaction. Those who do not show up to take their medication are sent reminders and tracked down.

The monitoring system has already made a difference and cut the default rate in half, according to Batra.

“We have brought it down to three percent, and with our biometric technology we have brought it down to below 1.5 percent, which I believe is a huge savings," Batra says. "MDR-TB is not just human misery, it is a huge economic loss to the patient, to the country.”

With treatment centers in 3,000 Indian and Cambodian slums and villages, Operation Asha hopes its grass-roots effort, aided by technology, will help stem the tide of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis.