Widespread satisfaction over a pledge for the world to transition away from fossil fuels was tempered at COP28 by the failure of China and India — the world’s most populous nations — to endorse a related promise to triple their sources of renewable energy by 2030.

Experts attending the global climate conference that concluded Wednesday in Dubai said China was reluctant to sign onto the pledge because it has already had a major expansion in renewables in the past few years, making the goal of tripling current capacity that much harder.

In the case of India, the experts say, carbon emissions are already lower on a per capita basis than in most developed countries and the government feels it is unfair for the nation to be held to the same standards.

More than 120 other nations signed onto the pledge, which also calls for a doubling of energy efficiency in the same timeframe. The agreement calls for the world’s renewable energy capacity to be increased from the current 3,400 gigawatts to 11,000 GW by the end of the decade.

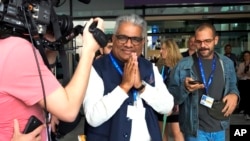

Francesco La Camera, director general of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) welcomed the agreement in an interview with VOA.

“This task is monumental. Yet it is achievable,” he said. “We believe it is the most realistic course-correction to urgently accelerate the global energy transition away from fossil fuels, trigger systematic change and overcome the barriers stemming from fossil fuels.”

China and India, however, will need to play a major role if the world is to reach its goal of limiting global warning to 1.5 degree centigrade. China is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide and India is the third largest, ranking behind the United States.

Both countries are also continuing to build new power plants fueled with coal, the energy source that contributes most to climate change.

Despite their refusal to sign the pledge, both countries have been supportive of the goal of tripling renewable capacity, according to Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Finland-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

“India's existing targets and commitments are already in line with this goal,” he told VOA. “China's current targets fall well short of a tripling, but the actual installations of renewable energy capacity in 2023 are already sufficient to achieve the tripling in practice if maintained until 2030.”

But, he said, China has made clear it believes something less than a tripling should be satisfactory in its case because of its large existing capacity.

Myllyvirta also said China also has qualms about the pledge to cut energy consumption per capita in half.

“China's economic growth has recently become more energy intensive and energy intensity gains have slowed down substantially, leading to difficulties in meeting the country's existing energy efficiency commitments, which it has also pledged internationally,” he said. “This makes the energy efficiency pledge tough for China to support.”

India, for its part, “has a valid argument that their current and historical emissions per capita are still low, so it's unfair for countries with much higher emissions to push them to commit,” Myllyvirta said.

“It's been a key part of [Prime Minister Narendra] Modi's message on renewables that they are being ambitious on renewables because they can, not because they have to."

Anders Hove, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, told VOA that China may also be reluctant to sign onto new commitments when it has not yet updated its own domestic targets, which will be determined as part of the next five-year plan.

Hove also noted that using the year 2022 as the baseline for a tripling of renewable capacity was a problem for China.

The 2020 baseline applied in the Sunnylands Declaration, issued jointly by the United States and China after a summit in California last month, “is a bit more fair, since that gives China some credit for its progress,” Hove said.