A halting and sometimes violent transfer of governing power is under way in Yemen and if the transition goes smoothly, one of the biggest beneficiaries could be the nation’s women.

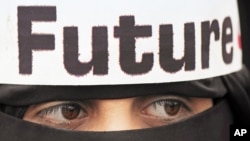

When protests rocked the capital Sana’a last year, part of uprisings across the Arab world, tens of thousands of women were prominent among the demonstrators, many taking a leading role.

Yemen’s president at the time, Ali Abdullah Saleh, responded by appealing to religious sensitivities, accusing the women of “un-Islamic” behavior.

Saleh is out of office now, forced to turn over power to Vice President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi this past February. But Yemen’s women are still demonstrating, still pressing for their rights and arguing that their cause is fully compatible with Islam.

In the forefront of that struggle is Tawakul Karman, a charismatic journalist, politician and women’s rights activist who led many of the anti-government demonstrations last year and became the first Arab woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Islam, like other religions, is not in conflict with women’s rights, democracy or any human rights principles or values like equality, justice and dignity,” Karman said in a telephone interview. “These are the values of the divine faiths.”

Convictions like these may be difficult to promote in Yemen, a poor and deeply traditional society where women have a literacy rate only half that of men.

Despite the difficulties, Yemeni women are pushing ahead, many using social media techniques to press their case. One of them is an activist and blogger who calls herself “NoonArabia.” She doesn’t use her real name because she still fears retaliation.

“There is nothing in Islam that says a woman cannot work or play [a] vital role in society beyond the walls of her home,” said NoonArabia. “Fundamentalists always misuse Islam as a means to suppress women.”

Yemeni men and women who want Sharia as source of new legislation:

Women 58% Men 68%

Women who believe they should have same legal rights as men:

Women 68% Men 53%

Women and men who agree boys and girls should have equal access to education:

Women 91% Men 90%

Men and women who support women working outside the home:

Women 87% Men 59%

Source: Gallup’s After the Arab Uprising: Women on Rights, Religion, and Rebuilding

According to NoonArabia, the main things hindering women’s progress in Yemen are social customs and tribal laws, not religion. Women who march in demonstrations, she said, are taking a “huge step in breaking the taboo barrier.”

“Yemeni women have proved themselves as partners in the struggle for change,” NoonArabia said, adding that their aim is to use their activism as a step to decision-making roles at all economic and political levels.

And the expectation among Yemeni activists is that Karman, with her Nobel Peace prize and prominent role in the ongoing uprising, will be leading the way.

“Women have to be present at all levels of the transitional government and future structures,” Karman said. “And this is what we’re fighting for. We don’t fight just for the rights of women as women, but as citizens.”

But Isobel Coleman, a Middle East scholar at the Council on Foreign Relations in (New York or Washington) advises caution when it comes to expectations about Yemen.

“This is a very traditional society,” Coleman said, adding that Yemen may have to undergo a “wholesale cultural revolution” before it deep-seated change is possible.

Yemen’s traditional resistance to change is, perhaps, most visible in Sana’a’s Taghyeer, or “Change,” square, which has been the symbolic center of the uprising since last year.

When the uprising against the Saleh government began in earnest last year and Change Square became the opposition rallying point, women were prominent in the demonstrations. They were side by side with the men as the uprising gained momentum and even slept in tents set up in the square.

Traditionalists were horrified and that’s when Saleh issued his decree that the women were behaving in an “un-Islamic” way.

These days, other opposition groups have taken the lead in Change Square and erected a shoulder-high wooden fence to separate the male from female demonstrators.

“Traditional gender segregation had insinuated itself into the center of the revolt from the Islamic groups who put a fence around them,” said Rahma Hugaira, president of Yemen’s Media Women, an opposition group.

She said many women demonstrators concluded they were being manipulated by political groups vying for power and decided to leave the square and give up the public demonstrations.

Complicating the political and rights struggle is Yemen’s ongoing violence. Tribal clashes continue unabated in the north of the country and the military is battling al-Qaida-linked militants in the south. In recent days, pro-Saleh factions of the military even tried to take over the Defense Ministry in Sana’a.

But Coleman of the Council on Foreign Relations said despite the violence and political upheavals, Yemen’s women have made their demands for equal rights an important issue in the nation’s political development. She said a more educated generation of women is emerging in Yemen and in neighboring nations and that demands for equality will only increase.

And Susan Markham, director of women’s political participation at Washington’s National Democratic Institute, said Yemen is “moving in the right direction.”

Markham said Yemeni women have established what amounts to “a school of scholars” studying Islamic texts and finding ways to accommodate gender equality with Sharia religious law – a necessity if further progress is to be achieved.

One signal of possible progress comes from Yemen’s Minister for Human Rights, Hooria Mashoor, who said the country’s National Women’s Conference has proposed adding language to a new constitution requiring a 30 percent quota for women in all state agencies.

The country is just beginning to discuss the content of a new constitution, but experts say the fact that women’s rights issues are being seriously discussed is an important step in an evolving process.

“No one can now marginalize them; and they are now moving on,” Mashoor said of Yemeni women.

“My guess,” said Coleman, “is there will be one step forward, one step back; two steps forward, one step back. But, you know, history is on the side of women.”

When protests rocked the capital Sana’a last year, part of uprisings across the Arab world, tens of thousands of women were prominent among the demonstrators, many taking a leading role.

Yemen’s president at the time, Ali Abdullah Saleh, responded by appealing to religious sensitivities, accusing the women of “un-Islamic” behavior.

Saleh is out of office now, forced to turn over power to Vice President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi this past February. But Yemen’s women are still demonstrating, still pressing for their rights and arguing that their cause is fully compatible with Islam.

Yemen Uprising Photo Gallery

In the forefront of that struggle is Tawakul Karman, a charismatic journalist, politician and women’s rights activist who led many of the anti-government demonstrations last year and became the first Arab woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Islam, like other religions, is not in conflict with women’s rights, democracy or any human rights principles or values like equality, justice and dignity,” Karman said in a telephone interview. “These are the values of the divine faiths.”

Convictions like these may be difficult to promote in Yemen, a poor and deeply traditional society where women have a literacy rate only half that of men.

Despite the difficulties, Yemeni women are pushing ahead, many using social media techniques to press their case. One of them is an activist and blogger who calls herself “NoonArabia.” She doesn’t use her real name because she still fears retaliation.

“There is nothing in Islam that says a woman cannot work or play [a] vital role in society beyond the walls of her home,” said NoonArabia. “Fundamentalists always misuse Islam as a means to suppress women.”

Yemen Gallup Poll

Gallup poll on Yemeni women's rights after the uprising:Yemeni men and women who want Sharia as source of new legislation:

Women 58% Men 68%

Women who believe they should have same legal rights as men:

Women 68% Men 53%

Women and men who agree boys and girls should have equal access to education:

Women 91% Men 90%

Men and women who support women working outside the home:

Women 87% Men 59%

Source: Gallup’s After the Arab Uprising: Women on Rights, Religion, and Rebuilding

“Yemeni women have proved themselves as partners in the struggle for change,” NoonArabia said, adding that their aim is to use their activism as a step to decision-making roles at all economic and political levels.

And the expectation among Yemeni activists is that Karman, with her Nobel Peace prize and prominent role in the ongoing uprising, will be leading the way.

“Women have to be present at all levels of the transitional government and future structures,” Karman said. “And this is what we’re fighting for. We don’t fight just for the rights of women as women, but as citizens.”

But Isobel Coleman, a Middle East scholar at the Council on Foreign Relations in (New York or Washington) advises caution when it comes to expectations about Yemen.

“This is a very traditional society,” Coleman said, adding that Yemen may have to undergo a “wholesale cultural revolution” before it deep-seated change is possible.

Yemen’s traditional resistance to change is, perhaps, most visible in Sana’a’s Taghyeer, or “Change,” square, which has been the symbolic center of the uprising since last year.

When the uprising against the Saleh government began in earnest last year and Change Square became the opposition rallying point, women were prominent in the demonstrations. They were side by side with the men as the uprising gained momentum and even slept in tents set up in the square.

Traditionalists were horrified and that’s when Saleh issued his decree that the women were behaving in an “un-Islamic” way.

These days, other opposition groups have taken the lead in Change Square and erected a shoulder-high wooden fence to separate the male from female demonstrators.

“Traditional gender segregation had insinuated itself into the center of the revolt from the Islamic groups who put a fence around them,” said Rahma Hugaira, president of Yemen’s Media Women, an opposition group.

She said many women demonstrators concluded they were being manipulated by political groups vying for power and decided to leave the square and give up the public demonstrations.

Complicating the political and rights struggle is Yemen’s ongoing violence. Tribal clashes continue unabated in the north of the country and the military is battling al-Qaida-linked militants in the south. In recent days, pro-Saleh factions of the military even tried to take over the Defense Ministry in Sana’a.

But Coleman of the Council on Foreign Relations said despite the violence and political upheavals, Yemen’s women have made their demands for equal rights an important issue in the nation’s political development. She said a more educated generation of women is emerging in Yemen and in neighboring nations and that demands for equality will only increase.

And Susan Markham, director of women’s political participation at Washington’s National Democratic Institute, said Yemen is “moving in the right direction.”

Markham said Yemeni women have established what amounts to “a school of scholars” studying Islamic texts and finding ways to accommodate gender equality with Sharia religious law – a necessity if further progress is to be achieved.

One signal of possible progress comes from Yemen’s Minister for Human Rights, Hooria Mashoor, who said the country’s National Women’s Conference has proposed adding language to a new constitution requiring a 30 percent quota for women in all state agencies.

The country is just beginning to discuss the content of a new constitution, but experts say the fact that women’s rights issues are being seriously discussed is an important step in an evolving process.

“No one can now marginalize them; and they are now moving on,” Mashoor said of Yemeni women.

“My guess,” said Coleman, “is there will be one step forward, one step back; two steps forward, one step back. But, you know, history is on the side of women.”