Torture in prison, chemical weapons, the direct targeting of foreign media, and hundreds of thousands of deaths. Syria's President Bashar al-Assad stands accused of a long list of crimes against his people.

Since the beginning of the conflict in 2011, journalists and human rights lawyers have been part of the process of documenting what appeared to be war crimes and abuses committed by forces loyal to the president.

As attempts to intervene by the international community largely failed, it fell to media and private citizens to demand accountability — and with some success.

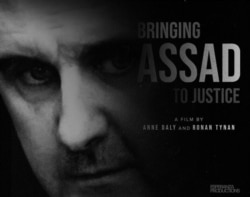

A new film, "Bringing Assad to Justice," highlights those efforts.

"People need to be made aware that Syria is one of the world's biggest crime scenes," said Ronan Tynan, the film's director, who is based in Dublin, Ireland. In Syria, "torture is systematic, disappearances continue, and hundreds of thousands have already been victims of these notorious crimes as well as arbitrary killing."

The United Nations said last month that Syria's decadelong conflict has left more than 350,000 people dead.

Rights groups say the Syrian government is largely responsible.

Assad's administration has denied accusations of war crimes, in some cases blaming opposition groups and their Western backers.

Collecting evidence

British journalist Paul Conroy is among the international journalists who have covered the conflict.

The photographer was with U.S. journalist Marie Colvin and French photojournalist Remi Ochlik in the city of Homs in Syria in 2012 when Syrian forces targeted their makeshift media center. The shelling killed Colvin and Ochlik and critically wounded Conroy.

The journalists had been in the city covering shelling and civilian casualties.

In 2016, Colvin's family filed a lawsuit in a U.S. court against the Syrian government for her killing, which included evidence collected by Syrian and Western journalists.

"After Marie was killed, we had to depend on local citizen journalists who paid a terrible price in deaths and disappearances," Conroy, who features in the documentary, told VOA.

"Evidence is the key to this, and it's been a joint effort all around. The Western press have played a part, but the real tribute should go to the young Syrian activists who've taken cameras and gone into the most horrifying situations to gather this evidence," he said.

In 2019, a U.S. court found the Syrian government responsible in the murder of Colvin, ordering it to pay $300 million in punitive damages.

Filmmaker Tynan said much of the archival footage he used in the film was produced by Conroy and local citizen journalists in Syria.

"These people are not just media workers; they are human rights defenders in the truest sense of that word. And without them, we would not have the evidence we have today against crimes against humanity in Syria," Tynan said.

Footage and accounts collected by citizen journalists have also been integral to the work of human rights organizations.

Since its founding in 2016, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), a France-based advocacy group that documents violations in Syria, says it has relied almost solely on local journalists to gather evidence of alleged crimes carried out by the Syrian government and other forces that have controlled various regions in the country.

In the Syrian context, citizen journalists have been playing a critical role in documenting abuses and crimes carried out by all sides of this conflict, said Bassam al-Ahmad, STJ's executive director.

"They go to places that other journalists can't go to. They have access to information and places that others don't," he told VOA. "The many chemical weapons attacks in Syria were first reported to the world by citizen journalists."

Rights groups have accused Syrian government forces of carrying out chemical weapons attacks against civilians across the war-torn country.

In June, the intergovernmental Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) told the U.N. Security Council that an investigation into 77 allegations against the Syrian government concluded that chemical weapons were likely or definitely used in 17 cases.

Syria's U.N. representative, Bassam Sabbagh, this month denied the use of chemical weapons. He said members of the OPCW were welcome to visit with the exception of one individual who, Sabbagh said, had failed to be objective.

Accountability

The International Criminal Court in The Hague has not been able to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Syria, citing lack of jurisdiction because Syria is not a member state of the Rome Statute, which established the ICC.

But several European countries, including France and Germany, have begun initiatives to hold Syrian government officials accountable for their crimes.

In July, a military doctor accused of torturing dissidents in military facilities in Syria was indicted by a German court on charges of crimes against humanity.

Tynan said two prominent Syrian lawyers and journalists, Anwar al-Buonni and Mazen Darwish, who are also featured in his film, have been instrumental in that case as well as helping to secure arrest warrants for Syrian government officials in Europe.

"There are many different justice initiatives going on," he said. "France and Germany have issued international arrest warrants against key [Syrian] regime leaders."

Journalist Conroy hopes the content and evidence the film gathered will contribute to achieving accountably for Syria.

"The Syrian people deserve justice, and I think it's up to everyone who's involved and sees what's happening to keep this story alive and point fingers and go 'these people should not be allowed back [into the international community],'" he said. "They are de facto war criminals, and they shouldn't be dealt with as if they are any other government who made a few mistakes."

"Bringing Assad to Justice" was released in Berlin on Wednesday and is available for viewing on digital streaming services.