At a central square in Serbia’s capital of Belgrade, dozens of Russians gathered recently to denounce President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine, holding up photos of political prisoners from their homeland.

Across the plaza, a billboard touts the Russian propaganda outlet RT, which has launched an online news portal in the country but is banned elsewhere in Europe. Heroic portraits of a bare-chested Putin adorn souvenir T-shirts and coffee mugs, or are painted on city walls.

These conflicting images reflect the complex and delicate relationship these days between Russia and Serbia.

The Slavic country is Moscow’s closest ally in Europe, with historic, religious and cultural ties that are bolstered by Kremlin political influence campaigns. Russia backs Serbia’s claim over its former province of Kosovo, which declared independence in 2008 with Western support. And Serbia has refused to impose sanctions on Moscow over the invasion.

At the same time, Serbia wants to join the European Union. Populist President Aleksandar Vucic has denounced the invasion, and about 200,000 Russians have flooded into the country in the past year, with many seeking a new life in a brotherly land free of Kremlin oppression.

“Here in Belgrade, we are not perceived with hostility, and that means a lot,” said Anastasia Demidova, who arrived in the Balkan nation from Moscow three months ago.

“I’ve been talking to a lot of Serbian people here and other foreigners. When they ask me ‘what are you doing here,’ I say: ‘We are against Putin and for a democratic Russia and we are against the war in Ukraine, obviously,’” she told The Associated Press.

Others say they fled to avoid being drafted or because Western sanctions crippled their businesses or took away their jobs.

As a result, Russian can be heard spoken everywhere in Belgrade, a city of about 2 million. Russian-owned restaurants and bars have sprouted. Private Russian enterprises have mushroomed, especially in the IT sector. The influx has sent the price of real estate soaring.

This reminds some here of the wave of Russians fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and many of those who stayed in Serbia left their mark on its culture and art.

These modern Russians, however, are maintaining links to their homeland, including financial ties, said historian Aleksej Timofejev. Unlike their predecessors, he said, they can’t go onward to the West because of the sanctions and still need visas to travel to richer countries in Europe.

“They did not choose this country but came here because it is the only one that would have them,” Timofejev added.

The newcomers say they can still feel Moscow’s heavy-handed influence, especially when it comes to Serbians’ approval for Putin, via media outlets like RT.

Russian activist Petar Nikitin calls it a “coordinated propaganda effort.”

Nikitin first came to Serbia in the early 2000s. Back then, “this admiration for the Russian government was a lot more marginal ... and I saw it grow exponentially,” he said.

Russians “who recently arrived, who didn’t know much about Serbia before, yes, many of them told me they were completely shocked to see this idolization specifically of Putin, and this picture of Russia that is completely divorced from reality,” Nikitin said.

Moscow has boosted this sentiment in the pro-Russia media by feeding Serbian anger with the West over Kosovo following the breakup of former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. The dispute between Serbia and Kosovo has been a source of tension since the war in 1998-99 that ended when a NATO bombing campaign forced Serbia to pull out of the former Serbian province after a bloody crackdown against Kosovo Albanian separatists and civilians.

Serbia’s rejection of Kosovo’s declaration of independence has Moscow’s support — one of the reasons why Belgrade maintains friendly relations with Putin and has refused to join Western sanctions.

While Vucic has criticized the invasion of Ukraine, he puts a uniquely Balkan spin on it.

“We do support territorial integrity of Ukraine, as we do support territorial integrity of Serbia,” he told the World Economic Forum in Davos last month. “So … they ask me, ‘Is Crimea part of Ukraine or Russia?’ Yes, it’s part of Ukraine. Donbas is part of Ukraine. If you ask us.”

His country “will stick to that, and we will be more loyal to territorial integrity of U.N. member states than many others that changed their stance on territorial integrity of Serbia,” Vucic added, referring to the support for Kosovo’s independence from Washington and other countries.

Western officials have stepped up pressure on Vucic to make a decisive turn away from Moscow if Serbia wants to join the EU. They fear that Russia could stir trouble in the Balkans through its Serbian proxies to avert some of the international attention from Ukraine.

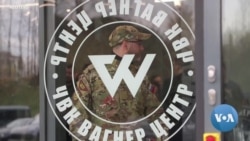

Recently, the Russian private military contractor Wagner Group ran advertisements on RT’s Serbian-language outlet recruiting Serbs to fight in Ukraine. It is illegal for Serbs to take part in conflicts outside the country, although about a dozen joined Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine after battles broke out there in 2014.

Owned by Putin-linked oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner has taken a prominent and active role in Ukraine and also has sent its mercenaries to several African countries. Last month, U.S. State Department Counselor Derek Chollet held talks with Vucic to voice concerns about Wagner’s activities in Serbia.

Nikitin, the Russian activist who has formed a group called Russian Democratic Community, has teamed up with a Serbian lawyer to file a lawsuit demanding an investigation of the mercenary group. That led to increased threats against more liberal Russians from right-wing Serbian organizations with close links to Wagner and Moscow.

“The threats that I receive directly and to my inbox are quite carefully worded — they are quite obvious,” Nikitin said. “They range from ‘get out of Serbia’ to very obscene insults involving my family. And veiled threats that I am soon going to meet people who are dead.”

Nikitin said his more liberal-minded countrymen in Serbia are eager to show they don’t support Putin’s war or his crackdown on opposition groups at home.

“We want to be very open about who we are and why we hold the views that we hold,” he said.

Artem, a 33-year-old web developer from St. Petersburg, said that he fled to Serbia with his wife and two pets shortly after the war began on February 24. He spoke with the AP on condition that his last name not be used for “safety reasons.”

Speaking at a Belgrade bar that’s an unofficial hub for more liberal Russians — its Wi-Fi password is “Nowar2402” — he said he’s been helping Ukrainian refugees in Serbia through online aid campaigns, providing information on how to start a new life.

Leaving Russia “was some kind of protest because I didn’t agree at all with the war,” Artem said. “War for me is not an answer for any conflict or anything.”