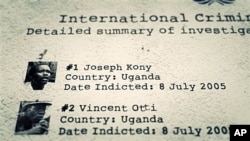

Tonight thousands of teenagers hit streets of the United States armed with T-shirts and posters as part of a campaign to make Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony even more famous than he already is.

In parts of Uganda, the U.S.-based group and its documentary have been accused of arrogance, over-simplification and misrepresentation of the country in order to make money.

In the northern region, a place ravaged by decades of LRA violence, reactions are more mixed.

Kony 2012 Teaser from INVISIBLE CHILDREN on Vimeo.

A place for survivors

Twenty kilometers outside Gulu sits a modest orphanage. Comprising just three concrete blocks in a tall grass, the structures are home to more than 30 children whose families were killed by LRA forces.

For many of them, capturing Kony is the only thing that matters.

For youth such as fifteen-year-old Nancy Apio, memories of the war between the Ugandan government and the LRA are still fresh.

"My dad was in the garden and then the rebels, they came and they killed him," she says. "They just cut him in two pieces. There was an uncle to me, he went to the garden. He was making charcoal. When they found him there, they killed him and they threw him in the fire."

A local screening

Most of these children have not seen Kony 2012, but several weeks ago a public screening was held in Gulu, and over 10,000 people showed up. It did not go well.

"When they went for the screening, they expected to watch a film where they were going to see Joseph Kony capturing young children, killing them one by one, and doing all the destruction that had been happening before," says Roy Arnold, a young man working in a Gulu café. "But then unfortunately, they brought a documentary where a white guy was speaking throughout the movie, and some young kid was playing."

According to 19-year-old Okane Francis Otim, an orphanage resident who was in the audience that night, things quickly got out of hand, and riot police were called in to control the crowd.

“They just started shouting, they destroyed many things," he says.

While Otim personally thinks Invisible Children’s campaign is a good thing, unlike many other Ugandans he says he would even be willing to wear a T-shirt with Kony’s face on it, if it would help the cause.

“That one I can do," he says, echoing a sentiment shared by most of the orphans. "It will be showing the sign that there is something that people should do, and that T-shirt will be showing it."

An unending war

For the orphans and their facility manager, the war is not yet over. Some are missing family members who were abducted and could be fighting with the LRA across the border in Congo.

"We have a girl whose father was taken, and up to now she still doesn’t know whether he is alive or not," says Apiyo. "But she is still having hope that one day their father will come back. So I believe if they come and then they chase away Kony, the relatives of people here will come back."

Fourteen-year-old Concy Attoo was born in a rebel camp in the bush, and has no memory of her parents, both of whom are dead.

"[My] life has been very hard, but at least things are improving," she says. "They no longer have to hide in the forest, and now they have enough to eat every day."

There is no question that things are looking up in the region. Although the LRA may have fled Uganda, says Apiyo, the campaign to capture Kony remains paramount.

"It’s not peaceful," she says. "What Kony has done ... led to poverty. People are still suffering, because some other people, they can’t produce. If you produce, and your leg is not there, how can you manage to get food for your children?”

One hundred U.S. troops were sent to central Africa last year to advise the Ugandan military in their continuing hunt for Kony, whose weakened rebel group is now scattered throughout the region.

Regardless of what they think of Kony 2012, many in Gulu hope the hunt for Kony succeeds.