Yirgalem Fisseha will never forget the moment her world turned upside down.

On February 19, 2009, Yirgalem, a poet and journalist, was working her shift at Radio Bana, a station in Asmara, Eritrea.

Suddenly, at 4 p.m., Yirgalem and her colleagues were ordered to an impromptu meeting. Government officials accused the station, which broadcast educational programs, of disloyalty. Uniformed soldiers surrounded the building and arrested about 30 journalists inside.

Officials held Yirgalem at Adi Abeto, a prison just outside the capital. As the interrogation dragged on and the questions became more bizarre, Yirgalem believed it was simply a case of mistaken identity.

The officers accused Yirgalem and other Radio Bana journalists of communicating with an opposition radio station.

“I thought, because they’ve already asked me so many questions, they were going to clarify things, and then they were going to send me home,” she said. “I was so confident about my innocence that I was worried about whoever did what they were asking about.”

But Yirgalem wasn’t released.

For the next six years, the government held her in solitary confinement, where she endured beatings and endless interrogations. After some time, they accused her of writing a subversive poem, lengthening her stay in prison.

She denies all charges against her.

“I didn’t even know that the radio station I was being asked about existed,” she said. “Most of my colleagues who were with me didn’t even know that this radio station existed.”

‘Brushed under the carpet’

Yirgalem isn’t the only Eritrean journalist to enter the government’s crosshairs. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Eritrea has 16 journalists in prison, making it the worst jailer in sub-Saharan Africa.

Year after year, the country ranks toward the bottom of press freedom indexes.

In September 2001, officials shut down much of the country’s free press. Seven newspapers were shuttered in the crackdown, and numerous journalists faced arrest. Some remain imprisoned to this day.

The government says the individuals it targets aren’t legitimate journalists, but rather pawns of opposition groups or foreign powers intent on subverting the ruling party.

Temesghen Debesai, a former anchor for state-run Eri-TV who now lives in London, said reporting on jailed journalists isn’t possible within Eritrea.

“To this day, nobody knows where they are, whether they’re alive or not. So that would have been a good story to cover,” Temesghen said. “But this is not the kind of story that you’re allowed to cover. It was just brushed under the carpet, and no one ever heard about them.”

‘No room for maneuver’

Outside Eritrea, family members, activists and government officials have pushed for the release of some of the jailed journalists.

Dawit Isaak, a journalist and Swedish citizen imprisoned since 2001, has been the subject of petitions, extensive global press coverage and diplomatic efforts by the Swedish government. His current whereabouts are unknown.

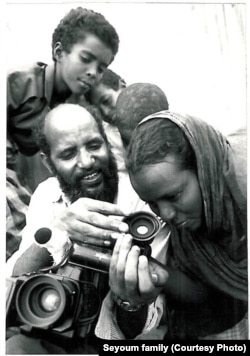

Likewise, Seyoum Tsehaye, a photojournalist imprisoned since 2001, has been held incommunicado for nearly two decades. His niece has taken up his cause and founded an organization, One Day Seyoum, to call for his release.

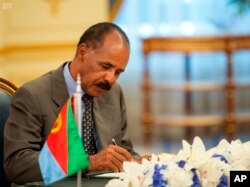

Today, no independent media outlets operate in Eritrea. Negative news about the country’s ruling party, the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice, or criticism of its president, Isaias Afwerki, is unheard of in broadcast or print media.

A handful of international news outlets have been granted access to the country, but the government monitors their reporters and tightly controls their access within the country.

For local journalists, the choice is simple: Broadcast positive news, or face dire consequences.

“There is no room for maneuver. It’s impossible for anyone. The people who work there have to survive,” Temesghen said.

“If they say anything that is out of line, you know, you’re going to get in trouble. But if you want to survive, you have to be able to stick to the rule book, which is sing praises. Say that everything is fine,” he added.

Outside reporting

There are some rays of hope for Eritrean journalism.

Exiled Eritrean journalists in France have founded Radio Erena, which relies on contributing reporters from across the globe and information secretly relayed from within the country to produce news programs in Tigrigna and Arabic. The station broadcasts back to Eritrea via satellite and shortwave radio.

Still, Yirgalem and other Eritrean journalists long for the day when a vibrant, independent press can return to their home country.

“For us, it’s been almost 20 years since it’s been formally forbidden to express our ideas. And within the past 20 years, we have forgotten that it is our right to express ideas, and we have become like we have no right to think, no right to listen, and we have no right to be silent,” Yirgalem said.

“We have so many people who are rotting in jail because they have been listening to other media outlets and radio stations. We have people in jail because they are thinking a certain way.”