Authorities in Egypt shut down the country's last remaining Internet service provider on Monday - essentially taking the entire nation offline. As officials take other measures including shutting down train service and limiting cellphone connectivity to try and slow the growing swell of protests, questions are rising over just how big an impact Egypt's tough tactics could have on other tightly-ruled countries across the globe.

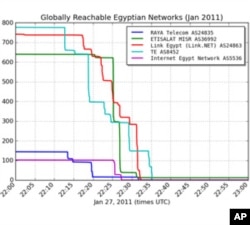

Late last week, Jim Cowie, the chief technology officer at Renesys - a company that monitors global Internet traffic - says his organization saw something unprecedented going on with the Internet in Egypt.

"As we watched it [the Internet] last Friday, we observed something that we've really never seen before, at that scale," he said. "All of the paths that go to Egyptian providers - with a very few exceptions - vanished. And in about the space of about 20 minutes, one by one, each of the providers of Internet service that has international connections in Egypt turned them off."

Watch Carolyn Presutti's Related Video Report

One ISP or Internet service provider did remain online, Noor Group, an ISP that services some 83 customer networks - including the Egyptian Stock Exchange, the clearinghouse for the stock market, multinational companies and other financial related entities.

But Noor Group, Cowie says, was taken offline on Monday morning as well.

"For them to undertake this level of disconnection from the Internet in such a, such a sudden blunt instrument kind of strike against themselves, that it took those of us who monitor Internet routing, pretty much by surprise," he said.

It also took activists by surprise.

"All of the Egyptian dissidents I speak with on G-Chat [Google Chat] suddenly disappeared in one fell swoop and they haven't reappeared yet," said David Keyes, director of cyberdissidents.org, an organization that advocates for the rights of online activists. He says that while authorities decision to pull what some are calling the "Internet kill switch" has made his work more difficult, it ultimately will hurt autocratic regimes.

"People will see this blunt instrument of shutting down the Internet for what it is: a great fear of the power of the people," he said. "And I think it actually might embolden dissidents and bloggers."

Internet experts note that Egypt is not the first country to pull the kill switch on the Web, similar tactics have been used in Burma, China and Nepal in the past. But, they say, it is the first instance where it has been so widespread.

And while authorities ordered ISPs to shut down, the public is still finding ways to circumvent the blackout.

Some have been using old fashion dial-up telephone services to connect to the Internet. Google and Twitter teamed up to provide a service called Speak2Tweet. The service allows individuals from Egypt and around the world to listen to and leave voice messages like this one on Twitter.

"Peace be with you. I'm Ehab from Cairo. I want to say one message. We are 85 million pharaohs. We fight this man, we want him to leave Egypt."

It is unclear how long Egypt's Internet blackout will last, however, most experts say it is unlikely to be too long, given the impact on society and the economy.

"The global economy is constructed around the Internet and around digital communication more generally, whether it be Skype calls or mobile phone calls having to do with international trade. It simply presupposes a robust ability to communicate internationally," said Steven Livingston, a professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University. He says Egypt's decision to cut off the Internet has undermined its already precarious economic situation.

"Egypt's economy is lagging, it needs as many observers have noted just to stay, to keep up with the need for jobs of a very large and young population," he said. "It needs to have the growth rates of China or India and it is far from that."

Although some authoritarian governments may see the Egypt model as a possible way of trying to squelch unrest, Jim Cowie, CTO of Renesys, adds that the growing need for connectivity could also serve as a deterrent.

"My hope is that other countries will take a look at this," he said. "Take a look at the economic impact and the reputational impact on Egypt as an information society that wants to grow a native information technology industry and attract foreign investment."

Last year, Egyptian officials say the information and communication technologies sector grew by 12 percent.

David Keyes, of cyberdissidents.org believes that despite the immediate effectiveness of pulling the Internet's kill switch, ultimately it is the public in Egypt and across the globe that has the upper hand.

"There are certainly ways that the regimes [in the region] try and use the Internet to their advantage and sometimes they are very successful," he said. "But ultimately information is an exceedingly difficult thing to stop."

Which is what some observers note has happened in Egypt over the past week. Where a growing number of protestors continue to pour out into the streets, even after the government took down Twitter, Facebook and the entire Internet.