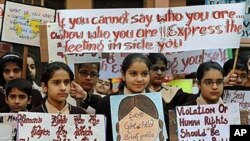

It's been 62 years since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was written and the anniversary is marked around the world Friday, December 10.

Femi Peters Junior is battling the Gambian authorities in order to get his father freed from prison. Femi Peters Senior is serving a one-year prison sentence in Gambia because, says his son, he organized a peaceful political protest.

"It's difficult not to have my dad around me. He's the head of our family and him being in prison is not very good for me. I'm 30 years old, I've got an 11-year-old brother back home, and at this age, I had my dad around me to guide me and support me. Now at this age he's not having that support and that hurts."

Peters has campaigned hard to get his dad released, writing letters and organizing rallies. So far to no avail, but it's the work of human rights defenders like him and his father that make the world better according to Claudio Cordone from Amnesty International.

"Human rights defenders are the most important vehicle for change. You often do not get change without fighting for it," said Cordone.

He says that's why it's important that people like Liu Ziaobo are celebrated. Chinese dissident Liu is this year's winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. His country, China, is one of the world's top human rights offenders says Cordone - but not the only one.

"Every region in the world, and in fact every country, has its own problems," he said.

The Britain-based business risk assessment firm Maplecroft released a report Thursday in connection with Human Rights Day. It ranks the Democratic Republic of Congo as the worst country for human rights, along with Somalia. Another three sub-Saharan African nations ranked among the worst 10: Sudan, Chad and Zimbabwe.

In Asia, Pakistan, Myanmar [Burma], Afghanistan, North Korea and China get the lowest marks, with Russia the worst in Europe.

Maplecroft maintains human rights around the world are getting worse rather than better.

It's a long way off from what Human Rights Day is designed to celebrate: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Chaloka Beyani, an expert in international law at the London School of Economics, however, said the declaration has brought change. He said he has seen its effects in the Great Lakes region of Africa.

"The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was of great value in putting in place a framework that would actually contain conflict and also move towards the resolution of conflict - from prohibiting member states to resort to the use of force to protecting specific rights including of internally displaced persons, sexual violence against women, so there's a huge effort," said Beyani.

He said many governments, though, still refuse to face up to what the declaration means in practice. "Within the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 21 says that the authority of the government is based on the rights of the people and yet we have seen many instances in Africa and elsewhere where election and their outcomes have been usually contested, from Zimbabwe, Kenya 2007, and now Cote d'Ivoire as we speak, where there was an election, a winner was announced, but the incumbent president refuses to leave office."

And it's that kind of abuse that affects the daily lives of people like the younger Peters. "I hope my dad lives to see my grand kids, if I have them, but most importantly I want him back for Christmas - that's all I ask for."

It's a simple wish for many around the world.