This is Part 3 of a 5-part series: Africa's Endangered Peoples

Parts 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

If the Gibe 3 dam is built, say an assortment of activists and experts, it will result in an environmental and humanitarian disaster affecting hundreds of thousands of people.

They say the dam will stop the flow of a river on which various indigenous groups in Ethiopia and Kenya have depended for their livelihoods for centuries.

The Ethiopian government, however, insists that the project, which will result in one of the world’s largest dams, is essential to generate much-needed electricity and will alleviate poverty “on a massive scale.”

The dam will hold back a reservoir 150 kilometers long and have a capacity of 14 billion cubic meters. At a cost of almost two billion U.S. dollars, it is Ethiopia’s biggest ever infrastructure investment. The Gibe 3 dam is nearing completion in Ethiopia’s Omo River valley; Gibe 1 and 2 have already been built and 4 and 5 are to follow.

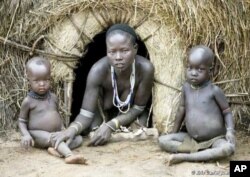

The valley has for centuries been home to several tribal peoples. The best known are the Mursi, whose women use plates to extend their lips. The people who live along the banks of the Omo keep cattle, fish, hunt game and plant crops.

“Because the river floods every year and floods quite large areas along its banks, they’re able to cultivate using the flood – so-called flood-retreat cultivation,” explains Dr. David Turton, an Oxford University anthropologist who’s been living among and studying the Omo people since 1969.

Each March and September, rains fall in the Ethiopian highlands, 500 kilometers away, and swell the Omo River so that it bursts its banks. The floodwaters enrich the soil with nutrient-laden sediment. When the water recedes, the people have fertile ground for planting their crops. As a result, they usually reap bountiful harvests of maize and sorghum in a region that’s mostly dry and unsuitable for agriculture, despite the presence of the river.

In a recent paper outlining the likely impacts of the Gibe 3 dam, Turton wrote, “Once the dam is in operation…river flow will be so regulated that there will be only a small difference between its wet season and dry season levels. The flood will be eliminated.”

This will leave the Omo people with largely infertile lands and their crops will fail, says Lori Pottinger, who researches the effects of large water projects in Africa for the International Rivers organization. The NGO seeks to protect waterways around the world.

Turton says, “Without flood-retreat cultivation, the bottom falls out of [the Omo people’s] economies.”

Government: Gibe 3 power will ‘transform’ Ethiopia

Ethiopia, like other African countries, is in an energy crisis. Most citizens don’t have electricity, and power shortages are hampering the manufacturing industry. The government says Gibe 3, through generation of hydropower, will end this “catastrophe” by expanding Ethiopia’s national power grid.

But an international energy expert, who asked to remain anonymous, questioned the feasibility of this, explaining, “There’s very small grid coverage throughout Ethiopia and the rest of Africa. Many of the populations, also in Ethiopia, are in remote communities. There’s no way that these governments can extend the grid from a large hydropower complex to use the electricity for their own people. It’ll cost too much. At best, they’ll be able to expand power to their capital cities.”

Pottinger, who’s also an energy analyst, agrees. She points to the Democratic Republic of Congo, which, as a result of the massive Congo River, “has the highest hydropower potential in Africa” and has built a number of large dams.

Yet, she says, the DRC “has cities of a million people with no electricity. Zero.”

But, in a recent statement, Ethiopia’s Ministry of Energy insisted the power generated by Gibe 3 would “transform” the country’s rural areas by “providing the basis for businesses in small towns and mechanized agriculture.” Ministry official Alemayu Tegenu said the dam would eventually lead to the electrification of 6,000 rural towns and villages.

Pottinger says for this reason, the Ethiopian authorities intend to sell most of the electricity to “big agricultural organizations, mining companies, and other countries that have a higher capacity to use electricity.”

This, she says, offers proof that the Gibe 3 undertaking “is not really aimed at improving the lives of poor Ethiopians, but at enriching the country’s political elite.”

The Ethiopian government has confirmed plans to export power from the Gibe 3 dam to Kenya and Sudan. Pottinger says the dam’s future depends especially on Kenya. “If Kenya decides not to buy any power from this project, it’s a little hard to imagine it going forward,” she reasons.

Dismissing all the criticism, Gail Warden, a spokesperson for the Ethiopian government, told Scotland’s Herald newspaper in June last year, “Westerners don’t want to hear about progress in Africa.…Anyone opposed to the dams should suggest alternative solutions to creating vast amounts of energy to feed the fastest growing non-oil economy in Africa.” Pottinger says she indeed has one such suggestion. She advises the Ethiopian administration to instead invest in geothermal energy, which is heated water from the earth’s interior used to run the turbines of conventional power plants.

“If they were looking ahead at what climate change is going to do to their rivers, they would as quickly as possible be diversifying into other types of electricity generation,” Pottinger states. “In East Africa that includes geothermal, which is a very clean energy source and this region has thousands, if not tens of thousands, of megawatts of potential in this respect.”

In a similar way, Professor Eric Odada, a member of the U.N. secretary general’s advisory board, cautions the Ethiopian government not to “bulldoze ahead” with Gibe 3 and to consider “alternatives” to the dam – “other renewable energy projects that are more sustainable against climate change.”

But the international energy expert interviewed by VOA says alternatives such as geothermal energy are “limited” and will only enable the electrification of small areas. “They’re not adequate to drive big industry,” he says.

Omo people to become ‘commercial farmers’

Another argument in favor of the Gibe 3 dam is that it will improve the lives of the people of the Omo River valley by giving them opportunities to become commercial farmers.

Turton agrees the reservoir will “indirectly create opportunities for large-scale commercial plantations in the lower Omo (valley)…The expectation would be that flood-retreat cultivation would be replaced by irrigated agriculture, which is certainly feasible and in some ways would be more reliable.”

Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi recently visited Jinka, the capital of the south Omo zone, to announce that a large part of the area would be converted to sugarcane plantations as a result of the Gibe 3 dam.

But Pottinger’s convinced there’s “little chance” of the Omo people ever being allowed to become large-scale farmers “in their own right.” She points out that some Middle Eastern countries have bought “huge tracts” of land in Ethiopia to farm to feed their populations.

The likelihood, says Pottinger, is that the Omo will end up “slaving” on the foreign-owned commercial farms. The Ethiopian government insists it will never allow this, and that it will support the local people to become formal landowners themselves.

Lake Turkana: another Lake Chad?

Activists, environmentalists and scientists say there’s much evidence to suggest that the construction of Gibe 3 will have a “devastating” effect on Lake Turkana. Situated in northern Kenya, it’s the largest desert lake in the world. It’s fed by the Omo River.

“Common sense tells us that a reduction of inflow from the Omo River will lead to the lake receding a lot faster than it’s already receding,” says Ikal Angelei, a local Turkana who’s also a member of the Friends of Lake Turkana lobby group.

Pottinger predicts, “This lake will probably go the way of Lake Chad – just drying up bit by bit.” Angelei says this would be “tragic” for the Turkana, who depend on the lake to water their cattle and for its fish.

“With the reduction in fresh water into the lake, we’ll have salinity increasing. The fish would not be able to survive with increased salinity,” Angelei explains.

“Should the…water become very saline and it then becomes acidic, then it’s not fit for consumption both for human and animal populations.”

She says lake communities “are already in conflict over scarce resources. A negative impact on the lake would exacerbate the conflict that we’re already suffering from.”

Scientists say if the Omo River stops flowing regularly, primary fish breeding areas in the shallows of Lake Turkana will “disappear.”

The Kenyan government says it’s “monitoring” the possible consequences of Gibe 3 for Kenya and will act in the “best interests” of its citizens.

The fight against the dam continues

Turton wants the Ethiopian government to formulate a “carefully prepared, detailed, systematic, costed scheme” to further investigate the consequences of the Gibe 3 dam on certain populations. The results, he says, could be used to make sure that people like the Omo “benefit and do improve their living standards” as a result of the project.

But, he says, “At the moment I’m afraid I don’t see any evidence of that.”

The Ethiopian authorities insist that all the necessary analyses of the Gibe 3 project have been done. Prime Minister Zenawi has vowed to complete the dam “at any cost,” accusing its critics of not wanting Africa to develop. “They want us to remain undeveloped and backward to serve their tourists as a museum,” he says.

Survival International, a group that lobbies for the rights of indigenous peoples, is calling for the project “to be suspended…until a complete and independent social and environmental impact study is carried out and the tribal peoples have been fully consulted and given their free, informed and prior consent” to the building of the reservoir.

Angelei says in the absence of an environmental impact assessment “free of state interference and influence,” the Turkana will continue to resist the building of the dam “in the strongest ways possible.”

Her group has appealed to the U.N. special rapporteur for indigenous peoples’ rights, the African Court of Human Rights and the U.N. Commission on Human Rights for “help” with regard to Gibe 3.

Pottinger refuses to accept that the dam is a “done deal,” even with Gibe 3 already two-thirds built.

“In Kenya, for example, people are demonstrating against this dam. People there are not backing down,” Pottinger says. “There have been dams that have been as far along as Gibe [3] is that have been stopped. So I’m not actually ready to give up the fight just yet.”