“John,” the editor of a small Native American tribal newspaper, asked that VOA protect his identity. His paper, like an estimated 72% of media outlets in Indian Country, is owned and funded by the tribal government. And because the government controls the purse strings, leaders say they have the right to control what gets printed.

“That’s why my paper is kind of tame,” he said.

He writes about community events, school sports, births and deaths, national news that affects the tribe, but said he never reports on tribal affairs —unless, that is, it is something that makes the leadership look good.

“I wrote something [negative] a few years back and almost lost my paper,” he said. Had the tribal government cut funds as they’d threatened, he would have had to shut down operations.

Native media today

Because they have long been overlooked by mainstream media, citizens of the 574 federally recognized Native American tribes in the U.S. have always relied on their tribes for news and information that affect their daily lives.

The 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA) made it illegal for tribal governments “to make or enforce any law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Many tribes have laws protecting First Amendment rights, but enforcement may be lax, and because tribes are sovereign, federal courts don’t have jurisdiction over civil rights violations.

In a 1998 article, “Protecting the First Amendment in Indian Country,” the late Yakama journalist Richard LaCourse described a number “interfering actions” tribal governments may take to stifle press freedom: hiring unqualified reporters on the basis of blood relation or political unity; firing staff; cutting funds; censoring stories before publication; blocking access to tribal government records and proceedings.

In 2018, the Native American Journalists Association, or NAJA, launched its Red Press Initiative, reaching out to members and asking them about the state of press freedom in their communities.

Only 65 media directors and producers responded, along with nearly 400 consumers. While not an exhaustive survey, it demonstrates that press freedom in Indian Country is inconsistent.

About half of the respondents said they faced censorship; a third said they were “sometimes or always” required to get tribal leadership’s approval before publishing stories; nearly a quarter said tribal government records and financial information were “probably” not open to journalists; and nearly half said they had faced intimidation or harassment by tribal officials or community members.

Today, NAJA says that a handful of tribal newspapers have managed to overcome these challenges and can serve as models for other tribes.

Rocky road to independence

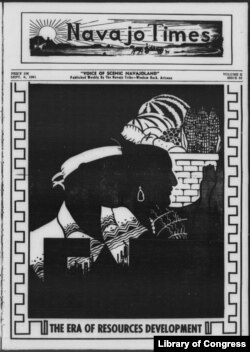

The Navajo Times, based in Window Rock, Arizona, is one of a handful of Native newspapers to have achieved full editorial independence, but it was decades in coming.

The paper began as a monthly newsletter in late 1959 to keep off-reservation boarding school students up to date on happenings back home. Over the next two decades, editors came and went, and relations with the tribal government were uneven.

In 1982, Peterson Zah was elected Navajo chief, replacing Peter MacDonald, who had held a stranglehold on the office since 1971. MacDonald was, according to one Navajo Times reporter, a man who didn’t like to “work openly and honestly with the press.”

But Zah felt differently and pledged to restore honesty and accountability to the tribal government, along with press freedom, which he said was “absolutely necessary in a true democracy.”

Zah lived up to his promises, supporting the paper even when it was critical of his policies.

“We were completely independent, if not downright ornery,” former editor Mark Trahant would later tell the U.S. Civil Rights Commission.

But Zah lasted only one term. MacDonald was reelected chairman in 1986 and shortly afterward closed down the Times—which had publicly endorsed his opponent—firing most of its staff. It relaunched four months later as a weekly paper.

Turning point

In 1989, a Senate Indian Affairs committee investigating corruption in Indian Country heard testimony that MacDonald was siphoning tribal money to fund his expensive lifestyle.

“It was a time of great turmoil and political divisiveness,” said Navajo Times CEO and publisher Tom Arviso, Jr., who had come to the paper as a sports writer in 1983 and by 1989 had been promoted to editor. “We just tried to tell the story of what was going on with the leadership and let readers decide for themselves.”

The Navajo Times covered it all, said Arviso, provoking anger among MacDonald’s supporters.

“People threatened me and some of the reporters with physical harm,” Arviso said. “A group of them actually marched to our office, telling me to come out and face them.”

On July 20, 1989, MacDonald announced he was taking back power. With his encouragement, several hundred of his supporters, armed with baseball bats and wooden clubs, stormed tribal offices in Window Rock. In the riot that followed, two people died and 11 were injured, including several police officers.

MacDonald was subsequently convicted on federal fraud, racketeering and conspiracy charges including inciting the riot. He was sent to prison.

Cutting purse strings

In 2000, Arviso was selected for a John S. Knight Fellowship in Journalism at Stanford University, where he studied newspaper publishing and business management.

“And that's how we came up with the plan to incorporate the Navajo Times, break away from the government and organize [it] as a for-profit corporation,” he said. “The bylaws state that the actual owners of the newspaper are the Navajo people themselves.”

The tribal council approved the plan in October 2003, and on January 1, 2004, the Times began operating officially as a publishing company.

“The tribe has asked that we make a return on the investment that the government has made,” he said. “But we don't just write a check and say, ‘Here’s $50,000.’ We give it back in services to our people.”

Today, the Times serves 23,000 paying subscribers and generates substantial advertising income. But what about smaller tribes, which could never hope to generate that kind of revenue?

Legislative route

When former newspaper reporter and publisher James Roan Gray was elected chief of the Osage Nation in Oklahoma in 2002, he was determined to shake things up. A century earlier, the U.S. government had passed a law restructuring the tribe’s government and membership qualifications.

“We were stuck in an old tribal council structure that really didn't give us much self-determination at all,” he said. “The BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] agreed with us.”

Gray envisioned an overhaul of the Osage government, and in 2003 took his case to Washington. H.R.2912, a bill to reaffirm the inherent sovereign rights of the Osage Tribe, passed and was signed as Public Law No: 108-431 in 2004.

“The law allowed us to reorganize our government, determine citizenship and chart a future of our own design,” Gray said.

After extensive consultation with tribe members, the Osage Nation drafted and approved its first constitution in almost a century. It contains language barring tribal government from making or enforcing any laws restricting a free press.

The tribe passed an independent press act, naming the Osage News as its official newspaper.

Gray also issued an executive order tasking the newspaper to report “without bias the activities of the government and the news of interest to foster a more informed Osage citizenry and protect individual Osage citizens’ right to freedom of speech or the press.”

He didn’t get everything he wanted: Gray had hoped that the executive branch would have sole control in naming the three-man editorial board. The tribe’s supreme court, however, ruled that tribal legislators would have equal say in the matter.

“We've all learned to live with that structure,” he said.

Since then, the tribe has amended the law to protect journalists from being forced to reveal their sources and prohibit leadership from defunding the newspaper.

Raising trust

Bryan Pollard, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, piloted the 2018 Red Press Initiative during his tenure as NAJA president. He cautions against making assumptions.

“It’s not always because there's an authoritarian regime that wants to control the message, although that exists in some cases. Sometimes, it’s simply because a tribe doesn’t have the capacity to develop the structures and institutions necessary for press freedom,” Pollard said.

Today, NAJA works with tribes and Native journalists to educate them on methods of achieving press freedom, and the ways in which it benefits both the tribal leaders and citizens.

“Society is better if it is informed,” said Gray. “Press freedom benefits the tribe if the tribal leadership values the trust of the people.”

Some tribal leaders don't trust their own citizens, he added, so they tell them what they think they want to hear “in hopes that it will get them reelected.”

“And if folks don't trust the contents of the tribal newspaper, then no matter what you put out, they're not going to believe you—or at the very least, they'll be skeptical,” Gray said.