Bumper-to-bumper on the Katy Freeway: the terrain is flat, and the air could soak a sponge. Heavy traffic covers 26 lanes.

Hot, hazy Houston, where roaches fly along Texas’ Gulf Coastal Plain — who would choose to transplant and call the city home? The answer is some of the world’s best doctors, scientists, engineers, chefs, artists, and entrepreneurs - highly specialized immigrants from Africa and Asia as well as an influx of laborers from south of the border.

They come for one reason only, a longtime Houstonian told VOA, the opportunity to make money. And except for its economic bust times, the city has provided that.

On the city’s northern edge, immigrant vendors from Thailand, Laos, Mexico, and more line Sunny Flea Market on Airline Drive, engaging in commerce. Within the tented marketplace, an Ecuadorian flutist draws families, while a nearby chef stirs carne asada and slices cilantro. Pakistani native Ismail Ali, observing Ramadan, sells spinners.

“Don’t mess with Texas,” says Ali, smiling.

Beginning in the 1980s, America’s fourth-wave immigrants entered the then booming oil economy of the south. Slowly, a biracial ‘Tejano’ (Mexican-American) city that once shared the state’s conservative stances on religion, gun control and illegal immigration transformed into a burgeoning progressive population, fourth largest in the country, that voted Democrat by more than a 12-point margin in 2016. President Trump, by contrast, won the statewide contest by nine points.

Today, Houston has a fresh face, and lays claim to the title of “most diverse” in the nation.

As goes Houston…

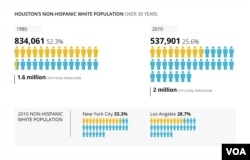

Houston's white population, like that in the rest of the country, has dropped over the last three censuses, the U.S. government's decennial count of the country's population.

In 1980, Houston's non-Hispanic white population was 834,061 or 52.3%. By 2010 the same group had fallen to 537,901 or 25.6% of the city's total population, which grew during the same 30 years from almost 1.6 Million in 1980 to 2 Million in 2010.

As Stephen Klineberg, founding director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research explains, a large proportion of non-Hispanic whites in Harris County — which encompasses Houston — is 63 years old and over. That population, he says, is “not going to be making a whole lot more babies.” By contrast, African-Americans, Asians, and above all Latinos surge in the age group under 20 and their populations continue to grow, according to new 2016 census data.

"You can go to the bank on this," Klineberg told VOA: "No force in the world is going to stop Houston or Texas or America from becoming more African-American, more Asian, more Latino, and less Anglo as the 21st-century unfolds. Nothing in the world can stop that."

Texan pride

Gilberto Zaragoza, an American from Guerrero, Mexico, sells cowboy hats at his father's stand at the flea market, while sporting a neon green and camouflage cap of his own.

Back in the early 90s, when his family was new to the country, he recalls his mother pointing to a menu, trying to order a hamburger or pizza in broken English, and being refused service.

"They didn't take that extra small step to try to understand us," Zaragoza said. But Zaragoza says he has personally experienced little discrimination in Houston, especially in recent years.

With time, Houston's attitudes toward new immigrants have shifted. According to the 2017 Kinder Houston Area Survey, 63 percent of Harris County residents thought immigrants to the U.S. "generally contribute more to the American economy than they take," up from 45 percent in 2010.

"I think Houston has always been welcoming to the immigrant community as far as the intentionality of the people of the city, but I feel like just in the last five years or so, it has become more organically welcoming," says Lee Hsia, downtown campus pastor at Houston's First Baptist Church. He moved to Houston from Shanghai, China, when he was seven and proudly calls himself a native Houstonian.

Hsia’s church welcomes Houstonians, including non-Christians, from more than 35 countries. “We have ‘welcome’ plastered through the front doors of our church,” he says.

What's so great about Texas? Let these Houston residents tell you.

The future of diversity

“There’s no crime, everybody keeps their property nice…," says native Houstonian Karl Casey. "[It's] an example of how people can live together without conflict.” But Casey laments that an entire day in the city may go by without hearing the English-language spoken, or flipping through the city’s daily papers and not finding what “upper-middle-class white people might be interested in.”

Respect for law is at the top of Casey’s values — a concern that is shared by many Texans, with regard to border security and immigration.

“I don’t believe that there is such a thing as an ‘unauthorized immigrant,’” Casey said, upset at strictures against using the word ‘illegal’ in regards to immigration. “I don’t believe you get to pick and choose what laws you want to obey.”

While demographer Klineberg sees Houston's demographic changes as inevitable, he wonders about how the city - and the country - will eventually handle them. "There is a law of human nature that says what I am familiar with feels right and natural; what I am unfamiliar with feels unnatural, somehow not quite right," he comments.

While recent arrivals are working towards the middle class, Klineberg notes a growing underclass of mostly white people with educations that do not go past high school, whose jobs in industries like coal and steel have disappeared.

"Every community is seeing a growing middle-class and a growing underclass, simultaneously,” Klineberg says. “And that underclass is the great question for the sustainability of Houston and America in the 21st-century."