This week marks the 90th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which gave women the right to vote.

One of the unsung heroes of the suffrage movement was Jane Addams.

Throughout her life, Addams struggled not only for women's rights, but also for labor and civil rights; free speech and world peace.

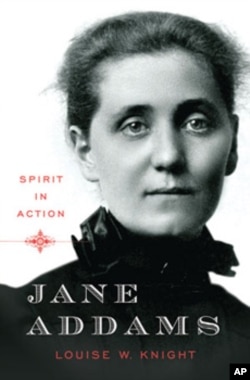

In a new biography, "Jane Addams: Spirit in Action," historian Louise W. Knight provides the first complete picture we've had of this activist, philosopher and social reformer.

Women's vote

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, voting was a remote dream for women in America.

Along with thousands of other progressive women, Jane Addams worked hard to turn the dream into reality.

"She first got involved in the suffrage movement in 1897, when she gave a speech for women's suffrage and she attended her first meeting of the National American Women's Suffrage Association in 1906 and from then on, she became quite active," says Louise Knight, historian and author of "Jane Addams: Spirit in Action."

Addams served as vice president of the association between 1911 and 1914. She traveled the country, lecturing and writing about suffrage. When the 19th amendment passed in 1920 giving women the right to vote, Addams became a member of the League of Women Voters, to help women become informed about the candidates and the issues on the ballot.

Fighting for civil liberties

Addams' fight for women's voting rights, Knight says, was part of a larger campaign she waged for civil liberties.

In her book, Knight follows Addams' struggles as a grassroots organizer. Her achievements include co-founding Hull House, the nation's first settlement house which offered educational and social opportunities for immigrants.

She co-founded the first national women's labor union and two major civil rights groups. She also lobbied for an eight-hour workday and an end to child labor.

What fascinates biographer Knight is how Addams - who was born to a wealthy family - was able to connect with the working class and to fight so passionately for their rights.

"She really believed you have to know people to understand how they look at the world and that's the only way you can be a true democratic citizen, kind of radical idea," Knight explains. "And she did it by living in a working class neighborhood full of diversity, of cultures and languages and backgrounds and work experiences, for most of her adult life, and forming friendships and partnerships with people from a completely different class than the one she was raised in."

Pragmatic reformer

That was one of the experiences that transformed Addams from a dreamy idealist into one of the nation's most effective and pragmatic reformers.

"It wasn't something she ever doubted, that she was superior. Even though she wanted to treat people socially equally, she felt morally superior and what she discovered by knowing people and living among them was that was not true," she says. "That just being highly educated or highly cultured, as her society put it, was not enough. In fact, it was inadequate, and that what real culture was she saw among her neighbors who were immigrants, who had lived in one world and now moved to another world. She saw a broader tolerance among working class people, a generosity of spirit she did not see among her own class. And that's what changed her view of the world."

Addams was a committed pacifist, and an outspoken opponent of war as an affront to the sanctity of life. Knight says Addams worked with other women to bring an end to World War I.

"Women from both sides of the war met in the Hague in 1915 while the war was under way, showing much courage, and they basically were saying to themselves, 'there must be something we can try to do to stop the war,'" she says. "And they did try. Of course, they did not succeed."

But after the war, women met again. They renamed the organization the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. The international group is still based in Geneva and has offices around the world.

Addams' commitment to the needs of others and her international efforts for peace were recognized in 1931 when she became the first American woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

If she were alive today, Knight says, Addams would urge women around the world to come together and organize themselves as a force for peace.

"Addams did not define peace as the absence of war, she defined it as, "the unfolding of worldwide processes making for the nurture of human life," Knight says. "And what she really meant by that was that it was a mistake to see some people as inferior whether based on their gender, or based on their ethnicity or their race or their class. So she thought you could advance peace through addressing those issues as well as addressing the issues of war."